Smokey Burgess Shot Down

From the book The Blood Assurance Story by Chris Dortch (ASIN:BOOZEDRJGO) - 2006

Available at Amazon.com

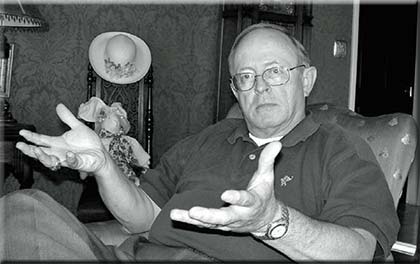

Related Information: Letter 19 Feb 1968 & Interview

...............................................................................................................................................

Just one more pass before lunch. Lee Burgess had been living a charmed life in the jungles of Vietnam. Since joining the United States’ conflict with the North Vietnamese in July 1967, Burgess, an Army helicopter pilot, flew dangerous missions every day, often more than one a day, without so much as a scratch.

Just one more pass before lunch. Lee Burgess had been living a charmed life in the jungles of Vietnam. Since joining the United States’ conflict with the North Vietnamese in July 1967, Burgess, an Army helicopter pilot, flew dangerous missions every day, often more than one a day, without so much as a scratch.

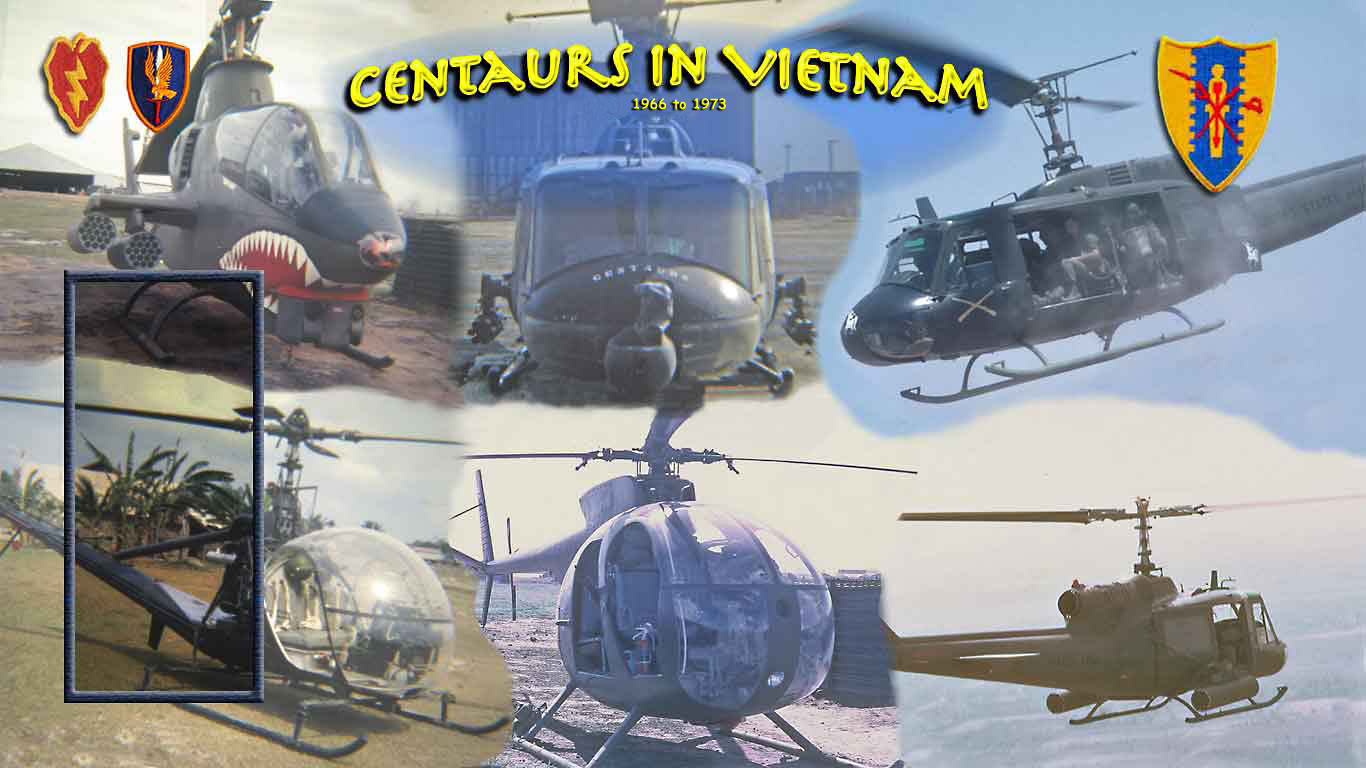

He left for Vietnam hoping to fly the UH-1 “Huey” gun ships, but instead Burgess was assigned to fly the much smaller OH-23 for the Light Scout Section of D Troop, 3rd Squadron, 4th Calvary. The Three-Quarter Cav, as it was called, was based in Cu Chi, about twenty-five miles northwest of Saigon, dead in the middle of some of the worst fighting in Vietnam.

“They [the OH23s] were light, very slow, but we were really good at what we did,” Burgess recalls. “We did the job that the old Indian Scouts did that were with the Calvary in the Southwest. It was our job to go out and find the enemy, pin them down and locate them and do what we could to attack them. But the main thing was to keep them pinned down until we could get artillery and air support or when we could get gun ships up there that were more heavily armed than we were.”

“They [the OH23s] were light, very slow, but we were really good at what we did,” Burgess recalls. “We did the job that the old Indian Scouts did that were with the Calvary in the Southwest. It was our job to go out and find the enemy, pin them down and locate them and do what we could to attack them. But the main thing was to keep them pinned down until we could get artillery and air support or when we could get gun ships up there that were more heavily armed than we were.”

Burgess’ helicopters had taken fire plenty of times before, but he never had reason to fear the worst; in his then- seven-month tour of duty, the Three-Quarter Cav had not lost a single pilot. Thus, on a February day in 1968, with the Vietcong’s infamous Tet Offensive still raging, Burgess decided that before he, gunner Billy Knighton and cre chief Harry Swiencki, along with a three-man crew in another OH23, returned to base for lunch, they would make one more pass over an area that was full of enemy units trying to retreat to safer ground.

The OH23s operated most of the time at treetop level, which left them vulnerable to attack. With just a quarter-inch thick steel plate protecting its occupants, and only a couple of 30 caliber weapons on board, the helicopter wasn’t equipped to engage heavy fire for long.

As Burgess directed the OH23 back toward the enemy, he could sense something was wrong. “Evidently I had made somebody pretty angry when I made that last pass,” he recalls. “Because they were waiting on us. We started taking a heavy volume of fire. I could feel the rounds hitting the steel plate on the bottom of the seat. The instrument panel was coming apart.”

Suddenly, an armor-piercing round struck the helicopter and passed through Burgess’ right arm, shattering bone and forcing Burgess to lose his grasp on the control stick. The helicopter stood nearly straight up as Burgess fought to regain control.

It seemed like a good idea at the time. Enrolled in the ROTC program while an undergraduate student at the University of Alabama in the early 1960s, Burgess heard about a program that sought students who had an aptitude for flying. “We could get our private pilot’s license at government expense,” Burgess says. “That seemed like a real neat thing for a young man in college to do. Little did I realize if I enrolled in that program and successfully completed it that I would have purchased my ticket for an all-expense paid trip to Vietnam.”

Burgess had actually volunteered for service, but at the time it didn’t appear the United States’ involvement in Vietnam would last that long. “At that particular time [1963] things were looking up,” Burgess told an interviewer for Virginia Military Institute’s Cold War Oral History Project in 2005. [Defense Secretary] Bob McNamara and John Kennedy said, ‘Well, it looks like we’re going to have all the troops home by Christmas.’ They just didn’t specify what year.

“I did volunteer—I was an only child and could have gotten a deferment for that reason—but my dad and my uncles, on my dad’s side of the family, all graduated from Clemson when it was a military school. My dad was in World War II all the way from North Africa into Italy, Normandy, the liberation of Paris, etc. So it just came naturally to me that was something I had an obligation to do.”

Burgess graduated from Alabama in May 1965 and began active duty in February of the next year. His first stop was Fort Sill, Oklahoma for officer basic training. From there he was sent to primary helicopter school at Fort Walters, Texas. He completed advanced helicopter and gunnery training in June 1967 at Fort Rucker, Alabama. One month later, Burgess and his helicopter were dodging bullets in Vietnam. It wasn’t until February 1968 that he finally encountered a bullet that had his name on it.

Burgess was bleeding profusely, but that wasn’t his only problem. Crew chief Bill Knighton, who had been shot in the knee and was also losing massive amounts of blood, was unconscious. Worse, Burgess had to try and land the helicopter with one hand.

“I could still see my right hand stuck up there on the control stick,” he recalled. “I had about two inches of bone sticking out; if [the bullet] had not hit something else first, it would have torn my arm off.

“Since I was right on top of the trees when I got the helicopter back under control, I couldn’t continue to fly because my left hand that was on the collective to make it go up and down was now having to be used to control the aircraft. So we had a controlled crash right in the middle of the area we had been firing in to.”

The helicopter hit the ground hard, but Burgess and crew chief Harry Swiencki, were able to get out, dragging Knighton along with them. Trained to stay near a downed aircraft because it’s easier to spot from the air, they took cover in a ten-foot bomb crater about twenty feet from the helicopter and behind thick foliage. Judging by the voices Burgess heard, he knew North Vietnamese soldiers were all around, and closing in fast. Burgess fired a few shots just to let them know he was armed. “For a few minutes, they didn’t fire back,” Burgess says. “Then we heard them on our left, as well as on our front. They were trying to move behind and in front of us to have us between two groups of them.”

That’s when Burgess made a decision. About two hundred meters behind his position was an abandoned rice field. It was their only escape. “If we didn’t leave right then, it would be too late,” Burgess says. “I was the aircraft commander. I decided we should run.”

Burgess, blood still pouring from his arm, led the way toward the rice field. Harry Swinski, the crew chief on board Burgess’ OH23, grabbed Knighton and carried him. Stopping for rest after reaching the rice field, Burgess tried to apply a tourniquet to his arm, which had nearly been split in half. It was no use; the damage inflicted by the armor-piercing bullet was too extensive. Thirty minutes had passed from the time the helicopter was shot down.

Knighton, who had been unconscious during the trek through the rice field, awoke with a grim realization. “Lieutenant, it doesn’t look like we’re going to get out of this, does it?” he asked Burgess. Burgess shook his head. Knighton then asked, “Will you pray with me?”

The three men said the Lord’s Prayer together.

“All of a sudden I was at total peace,” Burgess recalls. “My only concern was my mother, because I was an only child and I was going to be one of those people that was never found on the battlefield. I wondered what she would be going through, the anguish this would cause her.”

It was now close to an hour since the helicopter was knocked out of the air. Burgess and Knighton were getting weaker, their loss of blood reaching a critical stage. The men didn’t have a radio to contact their unit. Enemy soldiers were still scattered throughout the area. Just when the three men were at the brink of despair, their unit found them, tipped off by a helicopter pilot, who, even at treetop level, spotted the trail of blood left by Burgess and Knighton.

“We later were told that an order was given that they were not to come in and pick us up because there was too much [enemy firepower] down there,” Burgess said. “They had already lost one plane. But the aircraft commander, Warrant Officer Bill Gold, made the decision to come and get us.”

Burgess, Knighton and Swinski were piled into a Huey and flown back to Cu Chi. Burgess, who was close to terminal shock, was immediately started on a whole blood transfusion. Though he had been scant minutes from death, Burgess was revived and surgeons were able to save his arm. He returned to the U.S. with a chest full of medals—the Silver Star, Distinguished Flying Cross, Bronze Star, Legion of Merit, Purple Heart, Vietnamese Cross. Burgess attended graduate school and became a banker, eventually settling in Chattanooga, Tennessee.

From the book The Blood Assurance Story by Chris Dortch (ASIN:BOOZEDRJGO)

Note that the book had the crew chief and gunner positions reversed. That was changed on this page. Also the "D" was removed from "OH-23D" since all of our OH-23's were OH-23G models (Basically a souped up D model) bap Jun2020