The Rescue of Lady Ace - 11 Jul 1972

Chuck O'Connell, Fred Ledfors, Pete Holmberg, Bruce Keyes, Henry Bollman, Gary Knapp, Frank Walker,

Randy Baisden, Leon Ring, Joe Beck, Terrance Hawkinson, Stephen Lively, Mike Woods, Jack "Beetle" Bailey, Alan Zygowicz

additional information - also see Rescue of Lady Ace Video by Holmberg & Baisden

Contributing Documents

Lady Ace had 50 ARVN on board. Forty-three ARVNs & two USMC gunners perished. Seven survived.

1972 Easter Offensive

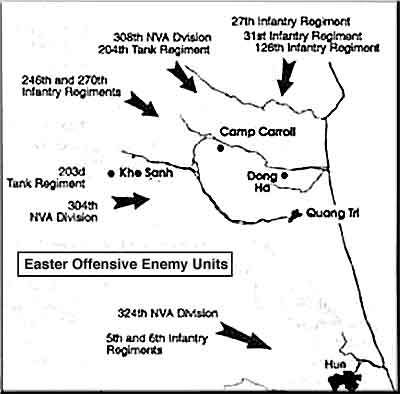

In March 1972, the North Vietnamese Army (NVA) staged the largest invasion of South Vietnam since the Tet Offensive of 1968. Invading across the DMZ from the north, the NVA easily overran the South Vietnamese Army (ARVN) and captured the city of Quang Tri. The sheer size of this massive assault caught the U.S. High Command by surprise.

In March 1972, the North Vietnamese Army (NVA) staged the largest invasion of South Vietnam since the Tet Offensive of 1968. Invading across the DMZ from the north, the NVA easily overran the South Vietnamese Army (ARVN) and captured the city of Quang Tri. The sheer size of this massive assault caught the U.S. High Command by surprise.

In response, the U.S. and South Vietnamese forces developed a counteroffensive named “Lam Son 72 - Phase II,” to recapture the city of Quang Tri. The strategy was to insert a reinforced battalion of ARVN Marines north of Quang Tri with the objective of retaking the city. The aviation support was a joint tactical operation of U.S. Air Force, Marines, and Army aviation units.

Marine Insertion Mission

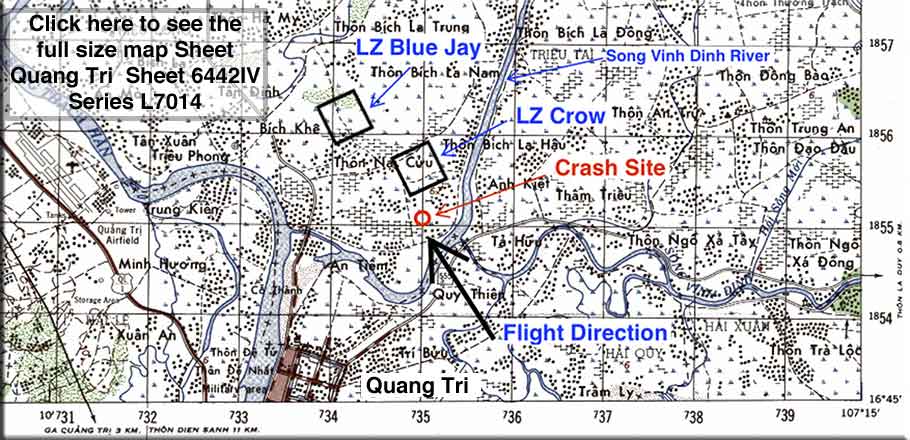

On the morning of July 11, 1972, thirty-four U.S. Marine helicopters picked up 840 ARVN Marines and headed for landing zones (LZs) Blue Jay and Crow, 2,000 meters North of Quang Tri City (see map below).

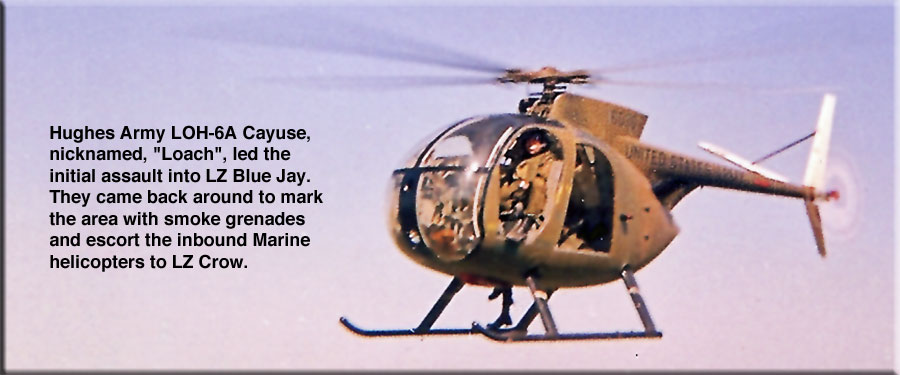

At 1150 hours, Army helicopters from F Troop, 4th Cavalry, call sign Centaur, led the initial assault into LZ Blue Jay. Captain Fred Ledfors and First Lieutenant Pete Holmberg each flying an OH-6A Light Observation Helicopters (LOH, nicknamed “Loach”) led the assault.

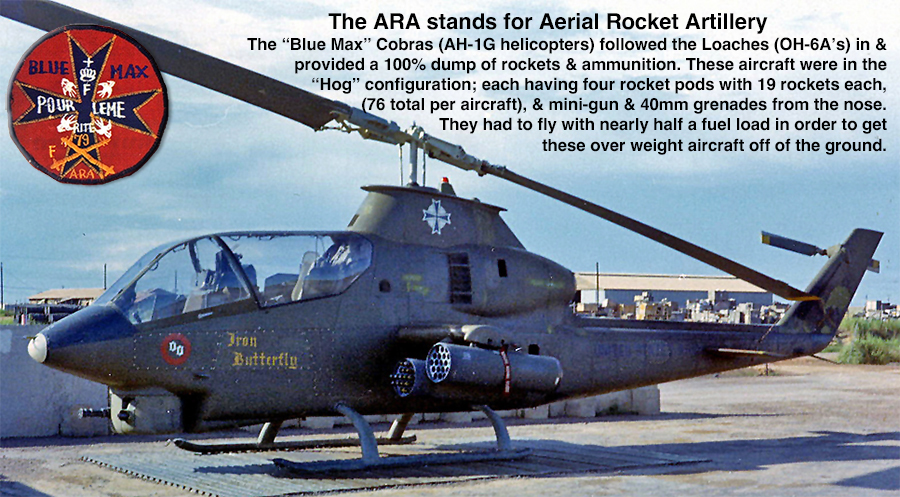

Following the two Loaches were six AH-1G Cobra gunships from F/79 Aerial Rocket Artillery, call sign Blue Max. The six Cobras, flying abreast, blasted the LZ approach path. Holmberg commented, “Canary (Ledfors) and I led the Blue Max Cobras in an all-aircraft-on-line, single-pass, 100% dump of rockets, grenades, and mini-guns. It was awesome!”

The two Centaur Loaches circled back to meet the first sortie (group) of Marine helicopters. Flying fast and low, Ledfors and Holmberg marked the far end of the LZ with smoke grenades and exited east. Eighteen Marine helicopters in three sorties flew toward the colored smoke that marked the LZ. When the vulnerable transport helicopters began their final approach, the NVA opened up with intense crossfire from AK-47s, anti-aircraft guns, .51 caliber machine guns and rocket-propelled grenades (RPGs). The Marine helicopters settled into the landing zone, offloaded the ARVN Marines, and quickly exited northeast. An observer from afar commented, “There were so many helicopters in the air, it looked like a school of sharks swarming.”

LZ Crow, “Hot as Hell”

After the last helicopter departed LZ Blue Jay, Ledfors and Holmberg rendezvoused with the first of three sorties of Marine helicopters (16 total) flying to LZ Crow. By this time, the enemy fire was described as “hot as Hell,” and the element of surprise had vanished. Again, flying fast and low, the two Loaches led the Marine helicopters toward the LZ. Holmberg reported, “The enemy fire was unbelievable, at one point two RPG rounds zipped across my flight path right between me and Canary.”

Arriving at LZ Crow, Ledfors and Holmberg marked the LZ with smoke grenades and flew toward the south end of the landing zone. “As I banked about 120 degrees to turn outbound, I saw an NVA soldier, without a helmet, on one knee, underneath the bamboo overhang along the edge of the LZ, about 200 meters from me,” said Holmberg. “He had a tube on his shoulder and he was looking straight at me. After violently completing a 90-degree outbound turn (being evasive), I immediately did an opposite 120-degree left bank while maintaining a straight course. The heat-seeker (Strela SA-7 missile) missed me by about 15-20 feet.” Holmberg and Ledfors, now low on fuel and ammo, returned to their base at Tan My.

Crash of Lady Ace 7-2

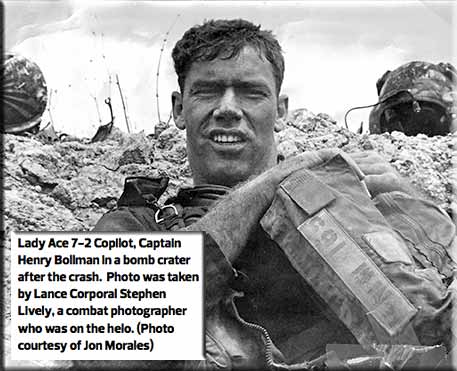

Flying a CH-53D (Sikorsky Sea Stallion) helicopter in the last sortie of five helicopters was Marine First Lieutenant Bruce Keyes, with the call sign Lady Ace 7-2. Onboard were the co-pilot Marine Captain Henry Bollman, the crew chief, another crewman, two U.S. Marine door gunners, and a U.S. Marine combat photographer. They were transporting 50 ARVN Marines to be dropped at LZ Crow.

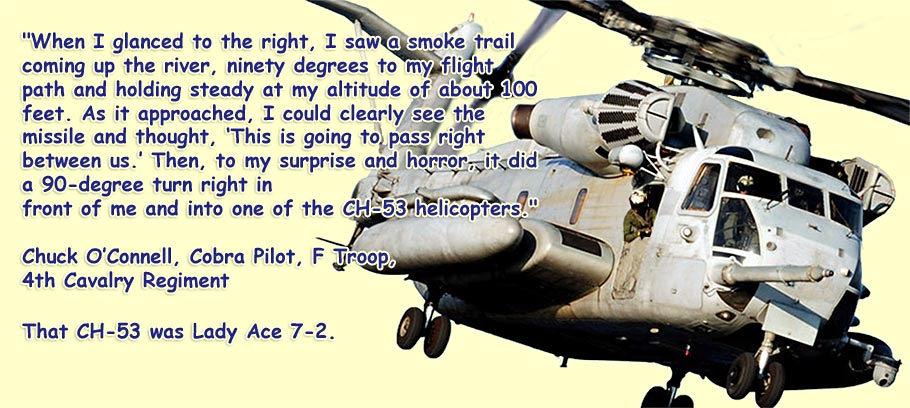

Enemy fire was intense as the Marine helicopters flared to slow for final approach to the LZ. U.S. Army Chief Warrant Officer 2 Chuck O’Connell, flying a Centaur Cobra gunship, was initiating his covering gun run in a northerly direction from the south side of the Song Vinh Dinh River when he saw a Strela SA-7 heat-seeking missile erupt from the river’s edge to his right. O’Connell stated, “When I glanced to the right, I saw a smoke trail coming up the river, ninety degrees to my flight path and holding steady at my altitude of about 100 feet. As it approached, I could clearly see the missile and thought, ‘This is going to pass right between us.’ Then, to my surprise and horror, it did a 90-degree turn right in front of me and into one of the CH-53s.” That CH-53 was Lady Ace 7-2.

The SA-7 missile made a direct hit on the starboard engine. The aircraft immediately burst into flames, filling the cockpit with a rush of fire and smoke. Miraculously, Keyes and Bollman, were able to continue flying the aircraft to a controlled crash landing. While the aircraft descended, the heat and fire continued to ignite the ammunition and fuel, causing a series of explosions.

The SA-7 missile made a direct hit on the starboard engine. The aircraft immediately burst into flames, filling the cockpit with a rush of fire and smoke. Miraculously, Keyes and Bollman, were able to continue flying the aircraft to a controlled crash landing. While the aircraft descended, the heat and fire continued to ignite the ammunition and fuel, causing a series of explosions.

The burning helicopter slammed into the ground. The surviving crew and passengers rushed to escape the intense inferno. The crew chief was on fire as he exited the helicopter wreckage. The pilot and co-pilot extinguished the fire on the crew chief while pulling him to safety. The two pilots, the injured crew chief, another crewmember, and the combat photographer sought shelter in a nearby bomb crater. The two U.S. Marine door gunners and all but seven of the 50 ARVN Marine passengers perished in the burning aircraft. The seven surviving ARVN soldiers evaded enemy forces and made their way to friendly Vietnamese units already engaged in combat.

Rescue Attempt

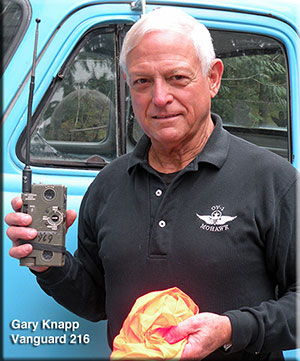

Minutes felt like hours as the Lady Ace crew hunkered down in the bomb crater while intense fighting erupted all around them. Roughly two hours passed as they desperately attempted to transmit a distress signal on their PRC-90 survival radio. Around 1400 hours, U.S. Army Captain Gary Knapp, call sign Vanguard 216, flying an RU-21 reconnaissance aircraft,

answered the emergency call and began talking to the Marines in the bomb crater. Knapp spotted the crew after they deployed an orange marker panel. He marked their location with his inertial navigation system, at grid coordinates YD350550.

Knapp contacted “King 26,” Air Force Search and Rescue (SAR). Two Sandy A1-E Skyraiders and a Super Jolly Green HH-53 helicopter were dispatched for the rescue. Knapp met the SAR team on the coast and led them inland to the crash site. On each approach, the rescue team was turned away by heavy anti-aircraft fire from multiple locations. Eventually, the Air Force SAR aircraft returned to their home base.

At 1530 hours, a reconnaissance (recon) platoon of ARVN Marines reached the crash site and moved the survivors to a more defensible location near the Song Vinh Dinh River. The sun was setting by the time they relocated. As the darkness began to settle over them, the Americans were losing hope and fearful of being captured. The odds against a successful night rescue were overwhelming. This was unwelcome news, made more so because three of the survivors were badly burned and desperately needed medical attention.

Centaurs to the Rescue

At 1845 hours, King 26 contacted F Troop, 4th Air Cavalry requesting their assistance.Fred Ledfors and First Lieutenant Frank Walker volunteered to attempt the rescue with their two OH-6A (Loach) helicopters. After a quick briefing, Ledfors and Walker launched their aircraft and headed for the downed Marines.

Walker was accompanied by Specialist 4 Randy Baisden, crew chief/gunner, and Sergeant Joseph Beck, observer/gunner. Ledfors’ Loach was equipped with a side-mounted 7.62 mm mini-gun, so he flew with a single crew chief/gunner, Sergeant Leon Ring. Following the Loaches and flying cover were O’Connell and First Lieutenant Russ Miller, each flying a Cobra gunship.

Nightfall had significantly reduced visibility when F-4 Cavalry received a second update on the enemy situation. An ARVN ground unit in the vicinity was engaged in hand-to-hand combat with NVA forces supported by armored vehicles, tanks, and artillery. Multiple anti-aircraft guns, 51 caliber machine guns, and SA-7 missiles were fired on any aircraft approaching the area. The ARVN Marine recon platoon, protecting the downed crew, was exchanging fire with NVA forces.

Dismissing the extreme dangers, Walker and Ledfors chose to continue the rescue mission. Shortly thereafter, Sandy 08, an Air Force A1-E Skyraider, intercepted the F-4 Cav Team at a location several miles from the recovery area and offered to lead them to the pickup zone (PZ). The four helicopters descended to near ground level with Ledfors in the lead. Walker trailed behind Ledfors and the Cobra gunships followed behind on each side, covering the flanks. Sandy 08 descended to an altitude of about 600 feet and lowered its flaps to slow its airspeed. Following Sandy 08, the four helicopters slowly flew nap of the earth, using terrain and foliage to conceal their aircraft.

It was completely dark as the Cav Team cautiously proceeded to the recovery area. Walker was asked how he was able to navigate when it was so dark with no moonlight. He replied, “It was God, adrenaline and my 24-year-old eyesight that enabled me to see with no light, in that order.”

Approximately one mile from the recovery area, all four aircraft and Sandy 08 began receiving heavy AK-47 and 23/37 mm anti-aircraft fire. Since they did not know the exact position of friendly forces, the helicopter crews could only return fire for fire. Walker’s crew chief, Randy Baisden, stood on the Loach skids outside the aircraft returning fire with his M-60 machine gun and guiding Walker around terrain features. “The NVA were all around us, entrenched in fighting positions,” said Baisden. “As we continued our approach, they fired AK-47s, RPGs, and anti-aircraft guns. At one point, we passed three NVA tanks, and the tank crew started shooting at us with AKs and 51 cals. We were so low and so close to the enemy that several times I had to ask Lieutenant Walker to go ‘blades up’ on the right side so I could return fire.”

The Rescue

Traveling northwest, the Cav Team approached the Song Vinh Dinh River. Miller and O’Connell, in Cobra gunships, broke left and remained on the south side of the river, entering a low-level racetrack (oval) pattern. At this point, the two Loaches ventured unprotected into a known enemy stronghold. They crossed the river and turned 90 degrees left, continuing their slow and deliberate approach parallel to and near the river’s edge. As they got closer to the pick-up zone, it became evident that the Marine survivors and their ARVN protectors were surrounded by the NVA. Baisden commented, “We had to fight our way in and fight our way out. The NVA were on all sides of the PZ.”

As the Loaches closed on the recovery area, Sandy 08 dropped a flare to mark the location of the stranded Marines. A short time later, the two Loaches lifted up and over a hedgerow and settled into the PZ. Walker announced, “Cease fire” as he maneuvered his aircraft to land within a few feet of the Lady Ace aircrew. He positioned his Loach to shield the survivors as they were loaded onto his aircraft. Baisden and Beck quickly loaded two U.S. Marines and a badly burned ARVN Marine.

Now carrying six people, Walker’s Loach was extremely overloaded. (Note: Ledfors’ Loach picked up three Marines and was now carrying a total of five people.) Walker instructed his crew to “lighten the load” by offloading boxes of grenades and all but 200 rounds of ammunition for the return flight. Then he deftly lifted the Loach light on its skids, but it was too heavy to hover. Walker slowly inched the overloaded aircraft forward, bumping along the ground as he tried to get “clean air” through the rotor blades for lift. It was so overweight that Walker ran out of left pedal and the overburdened Loach crabbed to the right. Walker “nursed” every bit of available power from the straining engine until he slowly gained altitude and airspeed, all the time receiving a hail of enemy fire from all directions.

Taking the lead, Walker chose a southeast departure, hoping to evade enemy fire. This departure path would cross the Song Vinh Dinh River at a location about 1,000 meters south of the first crossing. Directly ahead, on the riverbank, was a 15 to 20-foot tall embankment covered with mangroves and other vegetation. Just prior to reaching the embankment, Walker’s Loach entered translational lift (extra lift from the horizontal flow of air across the rotor blades), giving the aircraft additional power. The timing could not have been better. Walker flew up and over the embankment, barely missing the tops of the mangrove trees, and swooped down over the river, gaining airspeed.

Upon reaching the other side of the river, Walker and Ledfors resumed flying nap of the earth (10–15 feet of altitude), evading the enemy on their exit. Suddenly, on their right flank, two Strela SA-7 heat-seeking missiles came streaking through the night sky in their direction, passing above Walker’s Loach. Fortunately, the missiles were fired from such close range that they were well past the Loach before they could lock onto the heat signature of the turbine engine. “I was standing on the skids and saw the NVA missile crew at about 30 yards,” said Baisden. “I swung to the right and let loose with a blast from my M-60, taking them out.”

Cobra Shoot-out with Anti-Aircraft Gun

Seconds later, the two Cobras flown by Miller and O’Connell reunited with the Loaches. Miller joined up with Walker’s Loach, passing by high on Walker’s right side. Suddenly, NVA 37 mm anti-aircraft fire erupted from their left flank, passing in front of Walker and Miller’s aircraft. Walker recalls seeing Miller’s Cobra shudder as he quickly flared, standing the Cobra almost vertically on its tail. Simultaneously, Chief Warrant Officer 2 Terrance Hawkinson, Miller’s co-pilot-gunner, engaged the anti-aircraft gun with a hail of fire from his 7.62 mm mini-gun. Walker recalls it looking like a battle scene from a Star Wars movie. The night sky was filled with 37mm tracers from his left and 7.62 mm tracers from his right. As Walker’s Loach continued ahead, Miller brought his Cobra to a standstill, swinging its nose 90 degrees left to engage the anti-aircraft gun. From a hover, Miller and Hawkinson unloaded 2.75-inch rockets and 7.62 mm mini-gun fire into the gun emplacement in the tree line. Trailing Miller’s Cobra, O’Connell witnessed the maneuver and said, “It was great. Russ totally obliterated the anti-aircraft gun.” Later, it was reported that the Cobras silenced two anti-aircraft guns and destroyed at least one armored vehicle on their departure.

Walker continued flying evasively in a general southeast direction, choosing his path based on terrain and vegetation. Along the way, enemy fire erupted from all directions. Baisden stated, “At times, we flew directly over NVA gun emplacements, and I found myself firing my M-60 straight down between the skids.”

On Ledfors’ Loach, a different dilemma was playing out. In the rush to load the three survivors, crew chief Leon Ring wasn’t able to connect his safety harness. When they crossed the river and started receiving enemy fire, Ring was holding on for dear life as Ledfors put the Loach into extreme evasive maneuvers. “The enemy fire was much more intense on our departure,” said Ring. “We had rockets and anti-aircraft fire coming from all directions. I was holding onto the door frame to keep from falling out while firing my M-60 at the same time.”

Marines Returned to Their Ship

Once the Cav Team was clear of the hostile area, it was decided that because the Loaches were so overburdened, the rescued survivors should be transferred to larger Huey helicopters. They spotted a dirt road running through a rice paddy and Walker started his approach. Knowing his helicopter was too heavy to hover, he decided to make an approach directly to the ground. When the Loach descended through the last 15 feet of altitude, the rotor wash stirred up a dense cloud of dust, obscuring all visibility. Unable to see, Walker held steady on the controls and soon felt the skids hit the ground, and the struts bottomed out from the load. “I was completely blinded by the dust and flying at twice the certificate payload,” said Walker. “It was like someone else landed the Loach for me - and I believe someone else did land it for me.”

The six rescued survivors were transferred to two Hueys, and the four helicopters took off to join the other Centaurs for the return trip to their home base at Tan My. Arriving at 2000 hours, the survivors were given emergency medical treatment for their burns and other injuries. Later that night, the U.S. Marine aircrew was loaded aboard a Marine CH-46 helicopter and returned to their home ship, the USS Tripoli.

Afterward, Walker stated, “We never hesitated. We flew the night rescue because we realized our fellow soldiers were stranded inside enemy territory and their chances for survival were slim if we didn’t get them out. Bringing back those Marines was definitely worth the risk!”

The daring rescue was an outstanding success, especially considering the volume and intensity of enemy anti-aircraft fire and the task of locating the survivors in near-total darkness. Several days later, Bruce Keyes, the rescued Marine pilot, wrote in his report, “Heavily overloaded, we took off into the night for friendly lines, maneuvering and evading a withering hail of enemy fire with an aeronautical skill unequalled by anything I have ever witnessed. The coordination between the two Loaches and their Cobra gunship escort was uncanny.”

Combat Awards

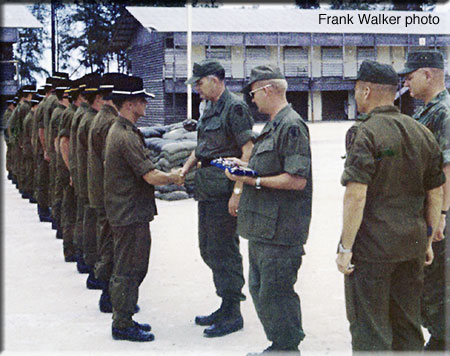

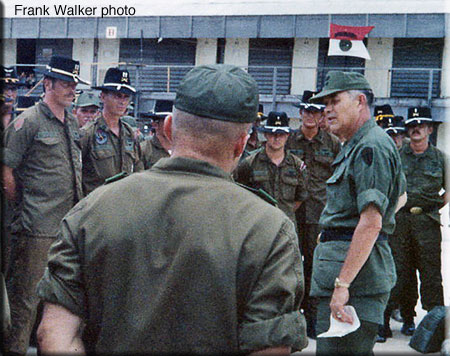

The following day, Army Major General Howard H. Cooksey, U.S. Senior Advisor, I Corps, and Marine Brigadier General Edward J. Miller, Commander of the 9th Marine Amphibious Brigade, visited F Troop, 4th Cavalry to recognize the heroic actions of the pilots and flight crew. General Cooksey awarded Impact Awards (field awards to recognize valor in combat) to the Centaur pilots and crewmembers, and General Miller congratulated and thanked the Centaur Troopers for rescuing the Marines.

It was here that a remarkable turn of events happened. Russ Miller, learned the general was awarding five Silver Star Medals; the remaining awards were Distinguished Flying Crosses and Air Medals. The general started down the line awarding Silver Stars, the higher award, first. Russ did the mental math and determined that he was going to be the last to receive a Silver Star. Standing to Russ’ left and positioned to receive a Distinguished Flying Cross was Walker’s crew chief, Randy Baisden, the brave trooper who stood on the skids while providing cover fire for Walker’s Loach. As the generals proceeded down the line presenting awards, Russ quickly traded places with Baisden, who received the Silver Star, and Russ received the Distinguished Flying Cross. As a result of this realignment, the Loach pilots and crew received Silver Stars and the Cobra pilots/co-pilots flying their cover received Distinguished Flying Crosses.

receive a Distinguished Flying Cross was Walker’s crew chief, Randy Baisden, the brave trooper who stood on the skids while providing cover fire for Walker’s Loach. As the generals proceeded down the line presenting awards, Russ quickly traded places with Baisden, who received the Silver Star, and Russ received the Distinguished Flying Cross. As a result of this realignment, the Loach pilots and crew received Silver Stars and the Cobra pilots/co-pilots flying their cover received Distinguished Flying Crosses.

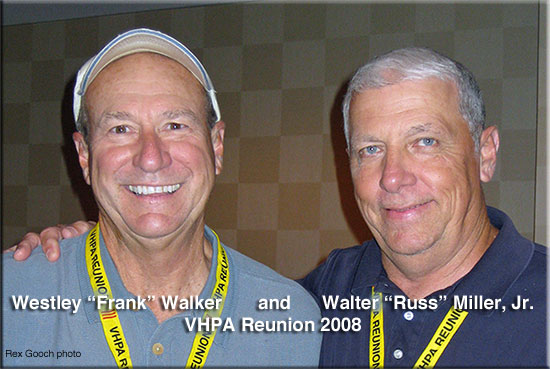

In August 1972, Walker and Ledfors were recommended to receive the Medal of Honor. In October 1974, the Department of the Army awarded Wesley F. (Frank) Walker the Distinguished Service Cross, the next highest award. In February 1975, Frederick D. Ledfors was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross.

In July 2008, the Army National Guard of South Carolina named a weapons range at Columbia’s Fort Jackson the “1st Lt. Wesley F. Walker Range” in recognition of Frank Walker’s status as one of the highest decorated soldiers to retire from the South Carolina National Guard since World War II.

Rex Gooch ©2015,

Call Sign: Longknife 23 - C/3/17 Air Cavalry, Vietnam 1971-72

Additional Notes:

Lady Ace 7-2 Crew:

Pilot: 1st Lt. Bruce G. Keyes

Co-Pilot: Capt. Henry C. Bollman

Crew chief: Staff Sgt. Clyde K. Nelson (died a month later from burns)

Crewman: Cpl. Lester E. (Sonny) Cox (burns)

Marine Combat Photographer: Lance Cpl. Stephen G. Lively (suffered burns and shrapnel wounds)

Door Gunner: Staff Sgt. Jerry W. Hendrix (died in the crash)

Door Gunner: Cpl. Kenneth L. Crody (died in the crash)

F-4 Cavalry Heavy Cav Team – Rescue of Lady Ace 7-2 on July 11, 1972

OH-6A’s - Loaches

1LT Frank Walker - Pilot (Rescue)

SP4 Randy Baisden - Crew chief/Gunner

SGT Joseph Beck - Observer/Gunner

CPT Fred Ledfors - Pilot (Rescue)

SGT Leon Ring - Crew chief/Gunner

AH-1Gs – Cobra Gunships

1LT Russ Miller

- Aircraft Commander (Rescue Cover Fire)

CW2 Terrance Hawkinson - Pilot/Gunner

CW2 Charles O’Connell

- Aircraft Commander (Rescue Cover Fire)

CPT Stephen Moss - Pilot/Gunner

CPT Michael Woods

- Aircraft Commander (Backup fire support)

CW2 Farrel Swindell - Pilot/Gunner

CPT Donnie Haynie - Aircraft Commander (Backup fire support)

1LT Richard Parrish - Pilot/Gunner

UH-1Hs - Hueys

CPT James Elder - Air Mission Controller (Command & Control)

CPT Jack Bailey - Pilot

SP5 Steven Webb - Crew chief

SP4 Jerry Evans - Gunner

1LT James Hogg - Infantry Platoon Leader

1SG Class Gilbert Carrasco- Infantry Platoon Sgt.

SP4 Edward Sodja - Rifleman

WO1 Daniel Miller - Aircraft Commander (Backup Support)

1LT Jim Dan Keirsey - Pilot

SP4 Matthew Mano - Crew chief

SP4 Johnny McReynold - Gunner

SGT Richard Dyer - Infantry Squad Leader

SP4 Paul Sofia - Rifleman

Jack "Beetle" Bailey - awaiting

Alan Zygowicz: The reason I am a Fan of the Centaurs is because they saved my life and the lives of a lot of other Marine Pilots and crew. The event occurred on July 11, 1972. It is documented in an article authored by Rex Gooch.

HMM 165 and 164 flew an insert and the Centaurs flew cover for us. Cpt Merlin Huckameyer and I flew lead on a section of six birds. We had Centaur Cobras on each side of us a we entered the LZ. As we flared to land, the Cobra on the starboard side broke left across our nose (yikes!) and engaged a tank that was driving down a road on our port side.

Later, when one of our CH 53’s got shot down by a SA 7. Frank Walker landed and picked up the two pilot. Everyone else in the bird died. The pilots got out via the pilot escape hatches. Frank flew them to a safe area, where Beetle Bailey who was in Huey, flew them to the hospital. Needless to say I owe the Centaurs.

Stephen Moss: I was with Chuck O’Connell that day flying his front seat. As I remember the day…numerous attempts to rescue the down crew were made. At last light we scrambled to race forward and make another attempt before dark. This means that anyone able was running to a seat in their aircraft to take off. It is entirely possible that the scout platoon Sargent was occupying a seat as this was a scramble. The fighting was intense. The tree line to the east and northeast was alive with green tracer fire shooting toward the flight. I expended the mini-gun, some four thousand rounds shooting the tree line some 250 yards away. The enemy fire from that location was intense. I switched to the 40mm grenade launcher when Capt Ledfors said he was coming out. He passed in front of us and we followed him out, the flight intact. There were only two Cobras forward and two covering the Huey crew and Lrp’s. Capt Don Haynie was covering the Huey. The next day much to everyone’s surprise we were all given impact awards from the I Corp Commander, I don’t remember any Marines at the ceremony. To my knowledge all Cobra crewmen were awarded DFC’s.

Contributing Documents:

Eyewitness Statement

On 11 July, 1972, I, Randy C Baisden, was flying as Crew Chief on OH-6A, Light Observation Helicopter, the wing ship of a heavy white team, during an emergency rescue attempt of five American Marine aircrewmen shot down north of Quang Tri City, Republic of Vietnam. My pilot was 1LT Wesley F Walker. Late in the afternoon we were scrambled to retrieve the five downed Americans. As we neared the LZ we received small arms, .51 caliber machine gun and numerous types of anti-aircraft fire from the enemy surrounding the LZ. 1LT Walker calmly flew his aircraft into the LZ, landing within a few feet of the wounded crewmen. He instructed us to throw out all our excess ammo to lighten the extremely overloaded aircraft. After the survivors were on board, we had to hover out of the LZ and during this time we took intense fire from 360 degrees around the helicopter. If it had not been for 1LT Walker’s extreme professionalism and skill as a pilot, the mission could have been a complete failure or possibly we could have fallen into enemy hands.

Randy C Baisden

SP4, E4

Eyewitness Statement

I, Joseph M Beck, was an observer on a OH-6A Light Observation Helicopter on 11 July, 1972, when we were scrambled to go on an emergency rescue mission to extract five American Marine crewmen of a CH-53 helicopter lost earlier in the day during an insertion north of Quang Tri City, Republic of Vietnam. My pilot was 1LT Wesley F Walker, and my crew chief was SP4 Randy C Baisden. As we neared the LZ we began taking heavy 23mm AAA, .51 caliber machine gun, automatic weapon and small arms fire. As 1LT Walker continued to fly toward the LZ in spite of the personal danger to himself, SP4 Baisden placed fire from his M-60 into the enemy position while guiding 1LT Walker through the fire and into the LZ. As we came over the LZ, SP4 Baisden ceased fire at 1LT Walker’s direction and guided him to a safe touch down next to the downed survivors. Throughout this whole maneuver, SP4 Baisden was standing on the skid of his aircraft fully exposed to the intense enemy fire. As the survivors were being loaded on the aircraft, 1LT Walker instructed both SP4 Baisden and myself to leave all but 200 rounds of ammunition behind to lighten the overloaded aircraft. Because of the overgross condition of the aircraft, 1LT Walker was forced to hover out of the LZ as the enemy tracers flew all around us. He also told us not to return the hostile enemy fire for fear of injuring the friendly troops in the area as we made our escape. Once clear of the area, 1LT Walker made a hazardous night landing to transfer the survivors to two of our team UH-1Hs. 1LT Walker and SP4 Baisden showed outstanding courage and professionalism throughout the entire mission.

Joseph M Beck

SGT, E5

Award of the Silver Star

19 September1972

General Orders #2654

Beck, Joseph M SGT 11C40

F Trp, 4th Air Cav (WGMJAA A)

Awarded: Silver Star

Date Action: 11 July 1972

Theater: Republic of Vietnam

Authority: By direction of the President under the provisions of the act of Congress, approved 9 July 1918, AR 672-5-1 and USARV Supplement 1 to AR 672-5-1 dated 10 August 1970.

Reason: For gallantry in action in connection with Military Operations involving conflict with a armed hostile force: Sergeant Beck distinguished himself by exceptionally valorous actions while serving as observer on the wing helicopter of a team on a voluntary mission. A lift helicopter had crashed in the midst of a North Vietnamese Army Division leaving five Americans and one Vietnamese Marine in a critical need of extraction. By the time Sergeant Beck’s team had arrived on station, nightfall had taken place, and the team had to expedite their efforts. Enemy units had the pick up zone completely surrounded, and very close and vicious fighting was in progress in the zone itself. When crossing two rivers, the observation helicopters came under a devastating barrage of small arms, automatic weapons, rocket propelled grenades, anti-aircraft, and heat seeking missile fire. Undaunted, Sergeant Beck gallantly provided accurate suppressive fire into the enemy positions. On short final another barrage of small arms and automatic weapons was directed against the team. At this time, Sergeant Beck engaged in a duel, matching his machine gun against an enemy machine gun at very close range. After a short, fierce exchange Sergeant Beck’s skill enabled him to partially neutralize the enemy nest. Still under intense fire in the pick up zone, he aided three wounded comrades to board his already heavily loaded aircraft with take off and acceleration extremely slow due to the heavy load. Sergeant Beck’s aircraft was again taken under heavy enemy fire. Sergeant Beck leaned out of his aircraft firing into well entrenched enemy positions until clear of the area. His extraordinary heroism and voluntary risking of his own life are in keeping of the highest traditions of the military service and reflect great credit upon himself, his unit, and the United States Army.