Iron Triangle LRP Rescue - 27 Aug 1968

by James W "Jim" and Dee Dee Filiatreault (daughter)

Mentioned in the story: Mike Galloway, Tom Meeks, plus Daniel Nate and Warren Nycum of 75th Ranger Regt

VHPA article and emails from Daniel Nate - Silver Star Award

also see his San Antonio (2014) video

.....................................................................................................................................................................................

After flight training, I got to Vietnam in March of 1968 to fly Huey Slicks, which are troop carriers. Nobody ever knew where they were going in Vietnam until they got there, and we thought it was a good deal getting assigned to the 25th Infantry Division. We would be the reactionary force for the LRRPs (pronounced “lurps”) – Long Range Recon Patrols – and if they got into trouble, we would go in and rescue them. A bad deal would be extracting in the mountains, but we were in the jungles and rice patties. The 25th Division’s area of operation was known as the “Iron Triangle” – an area of flatlands where the Vietcong had made massive tunnels underground; they even had hospitals under there.

After flight training, I got to Vietnam in March of 1968 to fly Huey Slicks, which are troop carriers. Nobody ever knew where they were going in Vietnam until they got there, and we thought it was a good deal getting assigned to the 25th Infantry Division. We would be the reactionary force for the LRRPs (pronounced “lurps”) – Long Range Recon Patrols – and if they got into trouble, we would go in and rescue them. A bad deal would be extracting in the mountains, but we were in the jungles and rice patties. The 25th Division’s area of operation was known as the “Iron Triangle” – an area of flatlands where the Vietcong had made massive tunnels underground; they even had hospitals under there.

At our camp in Cu Chi, we slept on metal beds in hooches about 30 x 60 feet long. All the pilots lived together in the pilot hootches. There was also a gunship hooch and Aero Rifle platoon hooch. We knew the guys we were extracting because we all slept encamped together. There was a center area boxed off with wooden crate parts. I used ammo boxes to make walls; I even made a little closet of my own with a light bulb in it. The hooch was covered by a metal pitch roof, surrounded by sand bags. Every morning like clockwork we were woken up by a rocket attack. They’d fire these 122 mm six-foot tall rockets from the river behind us. Somehow our hooch never got hit, but we were four down from one that did.

I came to Vietnam during the first TET in 1968. TET was the Vietnamese New Year, and the 1968 Tet was a full assault on Saigon and Long Binh to topple the south’s government. A lot of troop movement was happening to build up for an attempt at TET ‘69, and in August 1968, we inserted a six-member LRP team to observe an area and determine the strength of the enemy there. We always inserted the same six or twelve guys assigned to us. They were LRRPs special forces (F Troop, 75th Rangers), and they’d go out on “sniffer missions,” where they would find known paths of the Vietcong and plant satchels with machines in them that could detect any type of troop movement. Sometimes in the process, they’d come up on Vietcong, and they’d just hand-to-hand them right there. They would actually bring back necklaces with ears on them. These were some tough guys, always very cool and calm. And they always traveled with a Chu Hoi, Kit Carson, which was a Vietcong turned friendly who would serve as an interpreter.

August 27, 1968

After this particular insertion, the LRRPs reported back that they had come upon a full battalion of North Vietnam Army (NVA) with plenty of weapons. So an ARC light was planned, which is three B-52s flying in tight formation and just dropping bombs like rain. It’s five times the magnitude of what you’d see in WWII. It’s just total devastation. Congress had to approve an ARC light, and it was on the way. The plan was to extract the team before the ARC light, but that same day, the North Vietnam Army detected them. The LRRPs became completely surrounded by over a thousand men. The mission to get them out was delayed to see if they could move to a better position but soon night was upon us. And still the B-52 strike was on the way. You can’t just call a B-52 and say “Stop!” It has to go through all the same congressional channels to stop it, so our LRRPs were in the dark, being shot at, while bombs from the U.S. Air Force were on the way.

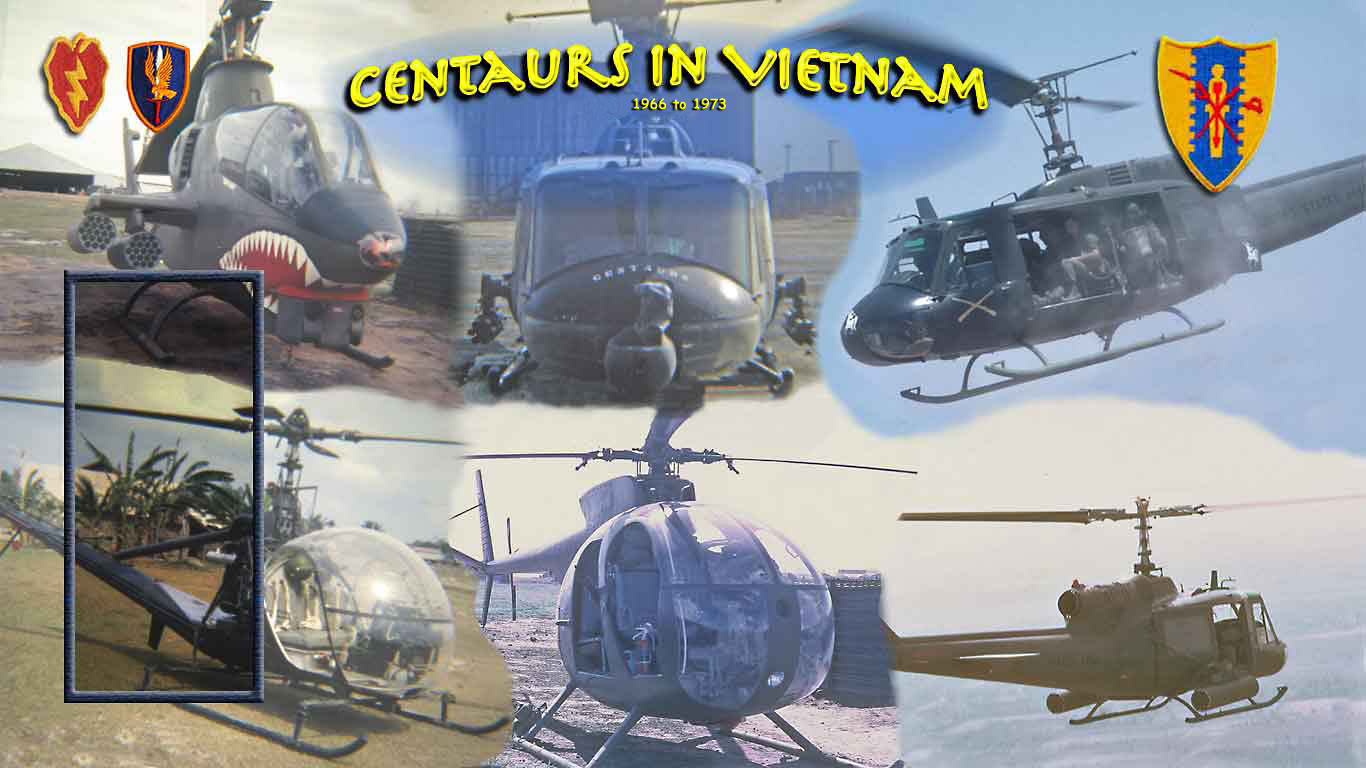

Our rescue team was made up of one Huey Slick, which was my aircraft; one Charlie model gunship, piloted by Mike Galloway; one AHIG Cobra helicopter, piloted by CWO Tom Meeks; and the command and control ship (C&C), which was another Huey Slick. The plan was that the C&C ship would fly high overhead at 4,000 feet, the Cobra would fly at 2,000 feet, the “C” model gunship would be above me to the rear, and I was to fly on the deck with no lights on.

I knew things weren’t right as soon as I heard the LRRPs on the radio. The LRRPs always whispered their instructions; this time they were screaming. All you could hear was hollering and screaming and gunfire and mortars. And it was pitch black. There was no moon, just total darkness. With all the gunfire and tracers flying in all directions, we couldn’t find them. The only guy who could see anything was Mike in the ship above me; he said he could see the silhouette of my ship against the explosions. The LRRPs aimed a strobe light stuck in the barrel of a grenade launcher at the sound of the helicopters, and I landed to that. The strobe was white, and all the other explosions were orange, so I would try to land to the white flash amongst all the red ones. The terrain was dense forest near a river, and there was just no good way to approach. There were some downed trees that had been felled some way, and I tried to land there, but it felt like landing in a hole; there were too many stumps and trees. I pulled pitch and overflew them. The LRRPs were just crouched down hiding and returning fire, while the NVA were shooting shoulder-held rockets at us. Artillery filled the air, which smelled of burnt gunpowder.

On my second attempt to land, I was coming in hot, and my Huey jerked and swung right towards my wingman, Mike Galloway, who called that he was hit with a rocket (RPG). I felt the backlash of it, and I immediately pulled pitch, thinking that I’d have to go rescue Mike. The rocket had blown Mike’s front skid off, but the ship was still flyable. Later I found out he got the rocket that was aimed at me. Somehow that rocket shot right between my rotor blades, hitting Mike above me…instead of me.

At that point, our company commander (in the C&C ship) told me to abort the mission. I totally ignored the radio, and decided to go back in. I mean, that was my whole reason for being there, to protect those guys. I knew I was the only way out for those guys, two of which were badly wounded. I mean, how could I just kick six guys to the curb?

I went in for the third rescue attempt on just pure adrenaline. Bullets and tracers were coming through the cockpit, and even though I had a door gunner and a crew chief, we couldn’t shoot our 30 cal guns. We were too close to the LRRPs to fire, so we were just naked. My only cover was the Charlie gun ship and the Cobra. It was total chaos. Those moments of screaming “Come on! Come on!” probably only took 15 seconds, but they seem like forever. Once all the men were accounted for and thrown into the ship, our guys started opening fire. They just melted guns and we kept on going. The LRRPs who got on were firing too, which I learned in an e-mail from one of the guys years later. Their translator had been killed, and their grenade launcher had been badly wounded. But everybody on their team was brought in, even the dead.

Mike was worried about his skid being blown off and the other bullet holes. So we didn’t try to make it back to Cu Chi; instead we opted to go to Dau Tieng. On the flight back, nobody’s talking. There’s always a formal debriefing afterwards, but other than that, no one ever brought it up again. You don’t talk about it. Once I’d landed and shut down the helicopter, though, I started vomiting horrendously. Too much adrenaline, I suppose.

My company commander was just there to advance himself and make himself look good. He knew he was in the wrong, so he never brought up the fact that I had defied a direct order. All the pilots heard our conversation because they’re all on the same radio frequency. So he never brought it up again.

There’s no other way to say it: God had a hand on my life. I mean, what are the chances of a rocket passing between a rotor blade turning 300 rpm – without hitting it? We had a thousand people shooting at us with God knows what kind of artillery, we had rounds coming in through the helicopter – but there wasn’t a single bullet hole in my aircraft. Not one.

******************************************************************************

In the Vietnam Helicopter Pilots Association (VHPA) newsletter in November 2000, I ran across this letter from LRRP Daniel G. Nate, which read:

“I wish the best for those great ‘Centaur’ personnel who kept us alive and brought us back to Cu Chi after each and every mission we completed, either from normal or ‘hot’ LZ situations. Without your professionalism and personal pride and integrity, none of us would be here now. You flew the lowest, you looked for us the hardest, and you never quit on us when the s*** was in the air. … Regardless of our position or predicament, you made us LRPS feel we were something special to your unit, and you always brought us ‘home.’ Thank you all. You are a special breed.”

I responded with an e-mail, inquiring if he was part of the extraction described above, and he was. He wrote the following reply on January 17, 2001:

“Jim, thank you and yours, and yep, you got the right team leader, team 2-1, out of Cu Chi. Thank you for ignoring the orders and getting us out of the jaws of hell. How do I thank you? I picked up the chu hoi scout and threw him in the ship and grabbed another guy, our M-79 man,Warren Nycum, who was down and greatly disoriented/lost and could not make it to the ship. I threw him in too, and then took a hit to my left leg and foot, got spun around and hit again in the back, right thru my ruck’s belt line. The round followed the belt line, but within my skin, and they cut it out of my lower stomach/intestine section later. About four months ago a message appeared on my computer, from Nycum, that stated “Nate sends me a Birthday every year.” In it he described the mayhem and the fact that upon seeing him and our scout go down, (I) left the ship and actually picked him up and threw him into the moving ship, damn near throwing him out the other side. You should be the one getting the thanks, and since I am the 75th Ranger Regt. Assoc. Advocate, you will get the credit, finally, that you deserve for that action. I only hope you didn’t get shit because of the order violation. If you did, we can clear it up now. Again, I thank you, as does my wife and our four now-grown children.” –Dan Nate

On October 16, 1968, the Silver Star was awarded:

“For gallantry in action: Warrant Officer Filiatreault distinguished himself by heroic actions on 27 August 1969, while serving as aircraft commander of a UH-1D troop helicopter with D Troop, 3d Squadron, 4th Cavalry in the Republic of Vietnam. Warrant Officer Filiatreault was assigned the mission of flying an extraction mission for a beleaguered LRP team. Warrant Officer Filiatreault made two attempts to land but was forced away by the intense hostile fire. Thinking only of the LRP team’s perilous situation, and with complete disregard for his personal safety, Warrant Officer Filiatreault elected to attempt a third landing. On the approach, the aircraft, again, came under intense automatic weapons fire. Unwavering, Warrant Officer Filiatreault skillfully landed his aircraft through a hail of enemy fire and evacuated the friendly LRP team. His valorous actions contributed immeasurably to the success of the mission. Warrant Officer Filiatreault’s personal bravery, aggressiveness, and devotion to duty are in keeping with the highest traditions of the military service and reflect great credit upon himself, his unit, the 25th Infantry Division, and the United States Army.” -- Signed by W.F. Faught, Adjutant General of the Department of the Army

“For gallantry in action: Warrant Officer Filiatreault distinguished himself by heroic actions on 27 August 1969, while serving as aircraft commander of a UH-1D troop helicopter with D Troop, 3d Squadron, 4th Cavalry in the Republic of Vietnam. Warrant Officer Filiatreault was assigned the mission of flying an extraction mission for a beleaguered LRP team. Warrant Officer Filiatreault made two attempts to land but was forced away by the intense hostile fire. Thinking only of the LRP team’s perilous situation, and with complete disregard for his personal safety, Warrant Officer Filiatreault elected to attempt a third landing. On the approach, the aircraft, again, came under intense automatic weapons fire. Unwavering, Warrant Officer Filiatreault skillfully landed his aircraft through a hail of enemy fire and evacuated the friendly LRP team. His valorous actions contributed immeasurably to the success of the mission. Warrant Officer Filiatreault’s personal bravery, aggressiveness, and devotion to duty are in keeping with the highest traditions of the military service and reflect great credit upon himself, his unit, the 25th Infantry Division, and the United States Army.” -- Signed by W.F. Faught, Adjutant General of the Department of the Army

............................................................................................................................

Tom Meeks: I do remember one mission that where pulled the LRRP’s out of a mix but (that happened frequently though). I don’t remember anything specific about that operation. Only vaguely remember that Mike Galloway lost a skid but am not sure of which operation.