What happens when the turbine engine quits (Flameout) on your overloaded Heavy Scout Gunship?

At the end of the story is a free verse poem "Emergency Reaction" by Bob Graham.

Other Centaurs mentioned: Herbert Caddell, John Alto, and James Thompson

Flameout With Herbert Caddell

While conducting a gun team combat mission (light fire team), flying visual flight rules (VFR) on top, LT Herbert Caddell and I experienced a flameout: then proceeded to an autorotation, jettisoning our rocket pods through the overcast for a successful power-off landing in the dry paddies near the Vietnamese Army Ranger School. No guts and glory just trying to stay alive.

Reminiscing

Herb arrived in country with D Troop assigned as a heavy scout pilot. Like me, he had a few years enlisted service and received his commission through Officers Candidate School. He was a very steady cool aviator, truly loved to fly and seemed to relish his military service for its potential for a better life.

We spent many hours in the air and on standby alert at the Air America strip along Highway (Go Da Hau). I have on file an image of him and a gunship crew with Vietnamese children. It seemed we were all beguiled by the beautiful innocent children.

The mission with Herb Caddell

Southeast Asia, Republic of Vietnam, 1966: May and June bring the season’s heavy moist mornings to the bustling Centaur Corral Heliport. Scouts and gun teams of D troop, (Air Cavalry), 3rd Squadron, 4th Cavalry Regiment, make their morning preparations for the adventure that a simple mission statement may bring. This understatement of combat, ‘‘One gun team support the Trang Bang Vietnamese Army Ranger School”, foretells little of the forthcoming day’s events.

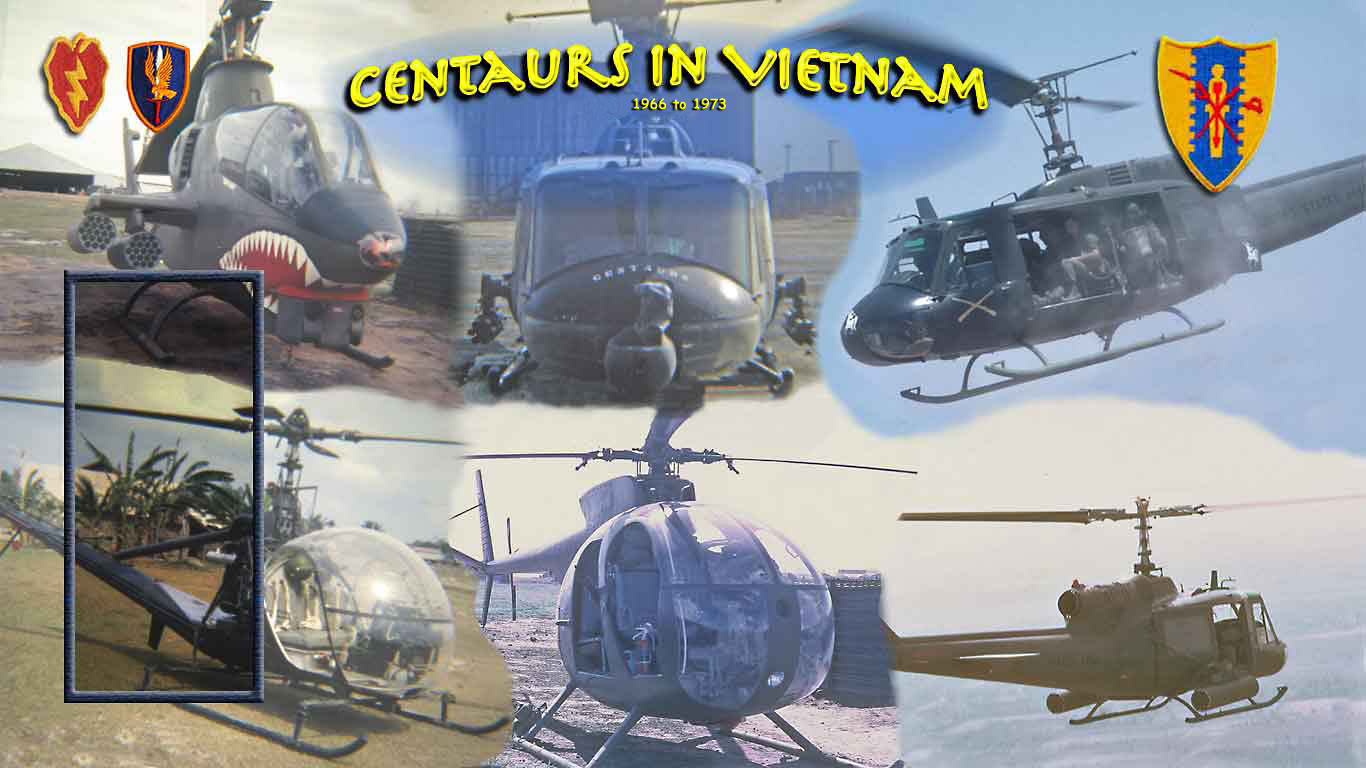

Without a comforting breeze, the crews have a light sweat just from conducting their preflight. My fire team is a mix with heavy scout (quad M-60s plus two seven round rocket launchers) and a Hog (two 24-round rocket launchers and a 40mm automatic grenade launcher) as wing. The crews have not even lit the fire and are already feeling clammy. The Cu Chi Army Airfield has not yet opened to VFR air traffic. The posted morning forecast is overcast with a 400-foot ceiling. Plus a situation report from an earlier flight of 1,000 feet clear on top.

Without a comforting breeze, the crews have a light sweat just from conducting their preflight. My fire team is a mix with heavy scout (quad M-60s plus two seven round rocket launchers) and a Hog (two 24-round rocket launchers and a 40mm automatic grenade launcher) as wing. The crews have not even lit the fire and are already feeling clammy. The Cu Chi Army Airfield has not yet opened to VFR air traffic. The posted morning forecast is overcast with a 400-foot ceiling. Plus a situation report from an earlier flight of 1,000 feet clear on top.

Within unit command procedures, U S Army aviation tradition delegated an aviator individual clearance authority. Each aircraft commander or fire team leader thus made his own decisions concerning acceptable weather conditions for a mission. As troop commander a few months later MAJ Peterson confided to me that he really agonized over ordering any of his crews to fly in weather conditions that might be beyond their capability.

I discuss the morning’s approach with my fire team wing man for answering calls for fire support from the Ranger School. We wish to take advantage of the thinning overcast as the morning progresses. The potential target area is flat dense jungle with numerous open areas; a 50-foot ground altitude, nearly level with the Cu Chi airfield. From our perspective the major concern is the extensive tree lines as sources of ground fire. We do not want to screw around low level, within range of every Viet Cong (VC) AK 47 in the Ho Bo Woods.

I elect to fly the left seat and control the quad M-16 machine guns. If called on a mission, I will lead the fire team up through the overcast on instruments on a radial of the Cu Chi Low Frequency homing beacon. Optimistically, I will then let down through an opening or thin spot near the enemy contact. Fire support will be delivered, and then we will climb back through the overcast and return to Cu Chi VFR on top for rearm and refueling. Flying low is either an on-the-deck two feet above ground 80+-mile-per-hour hazy adventure or flight within the to-be-avoided dead man’s zone, below 1,000 feet. Our experience supports waiting at Cu Chi until there is a mission versus standing by a bit closer at an unmanned Air America strip at Go Da Ha.

So we wait. I chat in the troop operations tent staying out of the way. My two crews are sitting in their ready-to-go gunships; just flick the master switch, light the fire and go. Briefly, the discussions ramble from the latest Armed Forces Network news to the recent tiff over an individual who was wasting precious ice. There had been a minor altercation among the troopers over someone throwing out the leftover ice after finishing a cool evening drink.

Sure enough, the inevitable call through squadron operations for fire support. I trot out the operations tent door, across the little bridge, signaling crank-em-up. Let’s go! As I approach I note that the main rotor tie down is off. It’s a total embarrassment when the tie down is inadvertently left on the blade tip. It makes a hell of a notable sound and the aircraft must be shut down, the blade stopped and the gadget removed. Then the embarrassed crew starts the sequence all over. Of course with everyone watching. Soon the turbines are humming. LT Herbert Caddell the copilot of my heavy scout is bringing the turbine up to full RPM as I strap into my armored seat.

Within minutes, the light fire team is hovering inches above the ground at the departure pad. The team pauses briefly; changes radio frequencies, checks the homing beacon indicator, readying for an immediate climb to VFR on top.

The early morning overcast has not yet burned off. The cloud ceiling is still too low for safe flight beyond the defensive barbed wire and bunkers of the 25th Infantry Division base camp perimeter. As planned, I request clearance to immediately climb to VFR on top. Minutes later we are level at 1,500 feet VFR on top of a near solid low overcast. As we continue toward Trang Bang there are a few thin patches in the overcast. Mystically below, faint tree lines can be detected among the dry rice paddies. The thinly veiled panorama drifts by like a beautiful Asian silk screen.

The Ranger School regularly patrol to their north and along the Ho Bo Woods. It is part of their training and also keeps the resident VC at bay. If they do not dominate the ground they are at the VC’s mercy.

A short time later during June, my light fire team was escorting a CH-47 in the same general area. It was loaded with General Weyand’s 25th Division General Staff less the G-4 on an area reconnaissance. It was shot down by heavy machine gun fire. D troop, primarily LT John Alto and his platoon of Aero Rifles, is credited with saving their day.

On the Ranger School FM command radio net, we hear the lilting broken English voice of the Vietnamese radio operator, “We have machine gun see tree line north blue smoke” I “Roger” the call and to all, “FIND THAT BLUE SMOKE”! The two crews immediately search below for our blue smoke clue. Then, my concentration is broken. I feel a major change in power, the ambient flight sounds change, and the Huey skews slightly.

Caddell crisply calls, “Engine RPM falling to zero, exhaust temperature falling.” In near unison there is a “flameout” call on the intercom. Instinctively, I bottom the pitch and begin a level deceleration, broadcasting, “This is Centaur 11. Engine out! Going down; east of the Ranger School.” Automatically, I decelerate to 60 MPH, holding my altitude and then begin an autorotation.

Every helicopter pilot has been at this precise moment many times during his flying career. It is the beginning of endless training proficiency and check rides of skill evaluations. But now there is really no safe power recovery; only a properly executed maneuver will end in success, and then only if we are fortunate enough to end up with enough clear earth space at the right place.

Our time to the ground from 1,500 feet is roughly 90 seconds at maximum gross weight. Caddell quickly selects the jettison stores’ switch. I nod and feel the Huey glide angle flatten as the two full seven-round rocket pods tumble away. Herb alerts the wing man to keep track of the falling pods of 2.75-inch folding fin aerial rockets. I stabilize the descent at a much more manageable 500 feet per minute. We all search intently through the overcast-haze layer for a suitable touchdown spot to bring this short drama to a safe end.

Herb again contacts Centaur Operations about the emergency, simultaneously switching fuel tanks, and I attempt a restart. Nothing! Only the sick little whine of the starting motor. Our real time clock seems to be running fast; the mere seconds have been consumed. Time is up! We are at 50 feet, and the focus is forward at the chosen spot, on rotor RPM, and air speed. Hopefully keeping pitch full down until the final flare and landing. Fate has chosen our landing spot; it is flat, dry and open. Herb continuously calls out the rotor RPM. The crew readies, all strapped in, for the touchdown. We are blessed. We have a dry rice paddy at least a football field away from the nearest wood line.

The last moves are ingrained but seem to be in slow motion, decelerate at 20 feet, stabilize. Reduce ground speed to zero. Settle level to five feet, keeping directional control and continue settling. Increase rotor pitch using up the rotor’s kinetic energy to touchdown lightly. Bottom pitch slowly so there is little skewing, and it’s over! The unpowered rotor blades make their last dying swishing sounds as I pull full pitch to slow them to a stop. Those last seconds seem like forever. The tension lowers a tad. The wingman has us under observation from above the hazy overcast. A small success for our crew.

I direct my wingman to conduct a quick low-level reconnaissance of the immediate vicinity for possible hostile individuals. He relays that they are sort of hyperventilating at troop operations about retrieving the full rocket pods we had jettisoned. They quickly report that there is no activity within half a mile and return to a safer standby on top of the haze layer. I ask, “What’s the plan, from operations! Come on, we’re parked in Charlie land and to hell with those damn pods.” They will get back to us shortly. He reports 50 minutes fuel remaining and we return to our immediate situation in a dry Nam rice paddy near no-man’s land.

The crew chief and door gunner are moved to hasty defensive positions on a low dike about 25 yards away. Herb remains on the radio reporting our assessment of fuel pump failure to operations. I climb atop the gunship to keep a better view of our surroundings. Although I can see the surrounding area and feel confident that there are no little people approaching, a pair of binoculars would certainly be handy to examine the tree line over two hundred years away. Now we wait for the arrival Captain James Thompson with the D Troop maintenance team.

We can hear our replacement gun team firing in support of the Ranger School. The sun bakes off the haze. Captain Thompson and the troop maintenance team arrives. Their Huey lands close by and I signal for my crew chief to return and assist the team. Herb and the team work out our assumptions about the failure and a new fuel pump is quickly installed.

Much to our amazement and relief we have not had a single hostile sighting. We hear the good news, the beautiful sound of the starting motor and scramble aboard. Herb nods and the power and rotor RPM indicator needle join the turbine indicator needle. Pull pitch and get the hell out of there! With everything back to normal we start back with a short low-level run, hopefully back-tracking to where we jettisoned the rocket pods. Nothing is seen within a half mile. Enough of this low level foolishness: we do a max performance climb through the haze to continue back to Cu Chi.

The fire in the Huey’s turbine burns out

The power needle goes to zero, no doubt

Now just the sound of wind

As blades free wheel about

For a whole crew it becomes

Situation delicate

Rotor sounds give clues

For the aviator intellect

Of energy saved

Actions to chose

Will there will be another day

Of your life to use?

If out of the bag

Of aviator tricks

The tested air warrior picks

The wrong little stick

The results not toasted,

But roasted, pondered in wonder

How could he select such a bad choice?

Such an aviator blunder!

In the chance of the

Aircraft commander’s draw

Select the single

Successful autorotation straw

They will toast

To your aviator skills, with awe

Copyright 2014 Robert L Graham