Gene Yonke, Dwight Birdwell, See videos from Mel Moss (2), Mel Moss (3), Tim Verver and Gene Peters

See story from Bill Schaffer - see all names mentioned in article - Gene Yonke input, Gene Peters input (1), (2)

..................................................................................................................................................................................

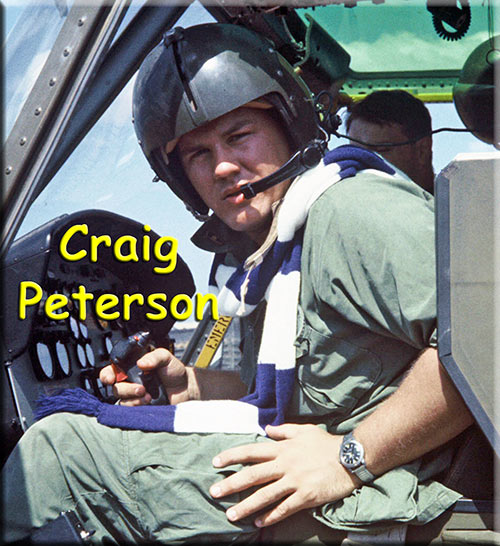

“He was there for us when no one else would come and he was there when we needed him the most.” So wrote Gene Yonke (A Troop, 3rd Squadron / 4th Cavalry Regiment) of Craig Peterson. The two men served together in Vietnam. Peterson was a helicopter pilot in D (Delta) Troop, 3rd Squadron's air wing.

“He was there for us when no one else would come and he was there when we needed him the most.” So wrote Gene Yonke (A Troop, 3rd Squadron / 4th Cavalry Regiment) of Craig Peterson. The two men served together in Vietnam. Peterson was a helicopter pilot in D (Delta) Troop, 3rd Squadron's air wing.

Dwight Birdwell was in C Troop, 3rd Squadron. He wrote:

If we were in trouble, Delta Troop always scrambled to our aid with lightning urgency … I have all the respect in the world for the regular dust-off medevacs, but the bond between the squadrons ground units and our Delta pilots and crews was such that they took chances for us that the dust-offs wouldn’t and probably shouldn’t have. Delta was fantastic. They just didn’t give a damn about enemy fire. They would let it all hang out, coming right on in no matter how hot the situation.

4th Cavalry refers to themselves as “MacKenzie’s Raiders”, a tribute to Major General Ranald Slidell MacKenzie, who commanded the regiment from 1870 through 1881 in the American West.

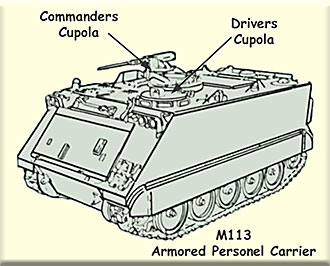

In Vietnam, each infantry division had a cavalry squadron assigned to it. 3rd Squadron, 4th Cavalry Regiment (3/4) was assigned to 25th Infantry Division. The first three troops of 3/4 Cav were mounted on tanks and armored personnel carriers, rather than horses. Armored Cavalry. The fourth, D Troop, in which Craig Peterson served, rode above the armored troopers in choppers; i.e., Air Cavalry.

Craig Leroy Peterson was born in St. Paul, Minnesota on November 30, 1946. He attended St. Paul Central High School, one of four major high schools in town and the oldest high school in the state. Craig was a good student and well liked. He played both basketball and football for the Minutemen. He graduated in June 1964.

Craig's parents gave him a baby blue 1956 Chevy just before he graduated. He rigged up a fine cassette stereo system in the car. Music meant a lot to Craig. He liked Bobby Vinton, Johnny Rivers and Peter, Paul & Mary. He enjoyed songs like The Beach Boys' megahit Surfer Girl and their 1964 song Don't Worry, Baby.

He enrolled at the University of Minnesota and studied there for two years. His heart was not really in higher education. Sometime during this period, Craig rolled his Chevy on an icy winter night. Craig finally decided that the university was not for him. He was restless. The war in Vietnam was deepening. U.S. involvement in Vietnam rose from just over 23,000 soldiers in 1964 to over 385,000 in 1966. Even light rock groups were releasing deeper songs; among them Bobby Vinton's 1966 hit Coming Home Soldier and his 1968 cover of the Bobby Vee hit Take Good Care of My Baby. In 1968, over 536,000 soldiers were committed in Vietnam.

Craig entered the United States Army on December 30, 1966. He learned how to tell an officer from an enlisted man and how to salute. He learned to march and to sing loudly in cadence while running in formation. After Basic Training, Peterson proceeded to the U.S. Army Primary Helicopter School (USAPHS) at Fort Rucker, Alabama. He learned to fly, but he also became proficient in navigation, instrument training and much more. They drilled on touch-and-go landings. Combat veterans taught tactics. Peterson completed the rigorous Warrant Officer Rotary Wing Aviator Course (WORWAC) and received his aviator wings and the rank of Warrant Officer on November 30, 1967. Craig Peterson, it seems, had been going to the wrong college before enlisting. The baby-blue Chevy was forgotten. He thrilled to the feel of power in the pilot's seat of a UH-1 helicopter.

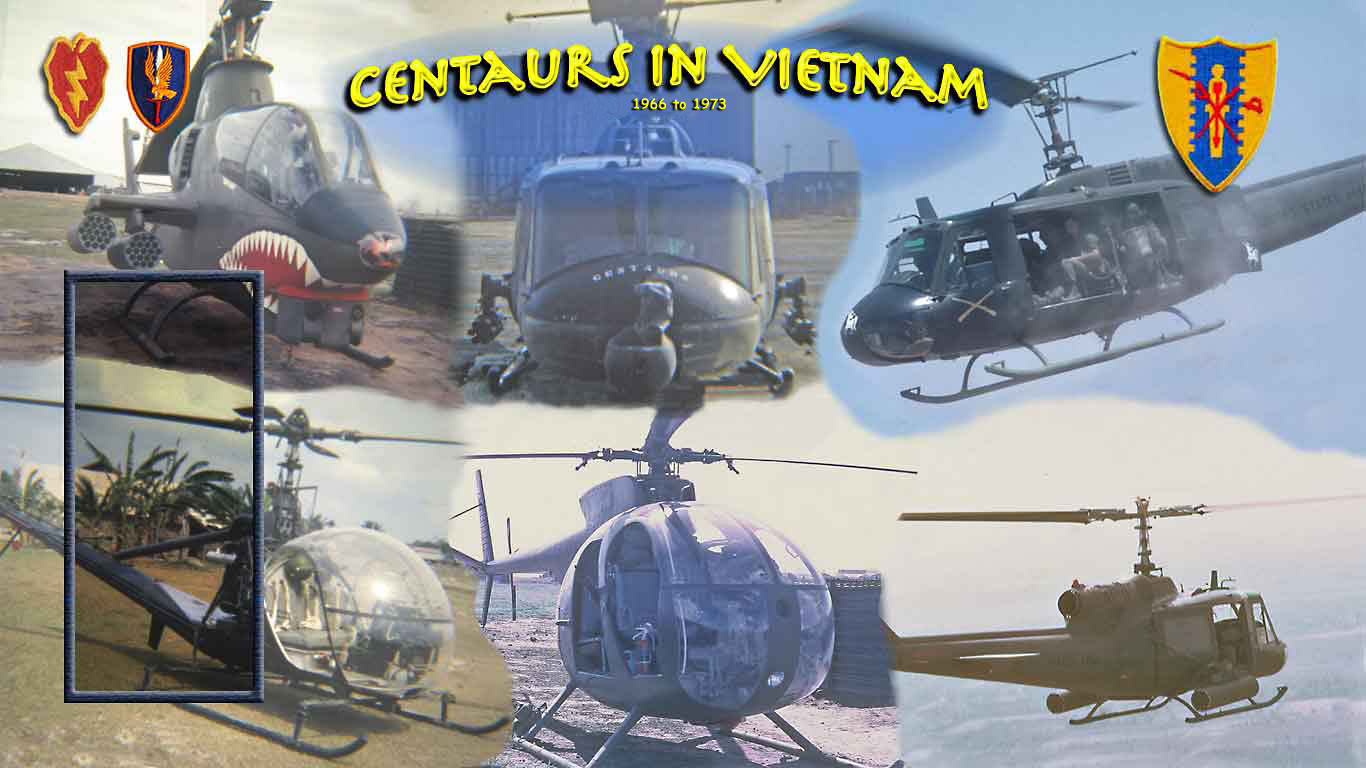

WO Peterson began his tour of duty in country on February 18, 1968, assigned to D Troop (Air), the Air Cavalry Troop, of the 3rd Squadron, 4th U.S. Cavalry. D Troop was known as the "Centaurs" and that was their radio call sign. 3rd Squadron was the recon and reaction force for the 25th Infantry Division. The mission of cavalry remained reconnaissance (to be "the eyes and ears" of the infantry division) and security (to screen, guard and cover advances and withdrawals of the division). The mobility and combined arms firepower of armor and air made the unit a formidable fighting machine.

Craig piloted a UH-1D Huey helicopter in the Aero-Rifle Platoon Lift Element. The crew of four included two pilots, a crew chief and a door gunner, the latter two armed with M60 machine guns. Four Hueys were responsible for carrying each of the four squads of ten infantrymen. They were on twenty-four-hour standby, always ready to head into trouble within minutes of the call for assistance. Peterson and his Huey also provided recon and fire support from the air. When intel was needed from the ground, the Hueys inserted and retrieved Lurps (Long Range Reconnaissance Patrols - LRRPs). During heavy firefights, all available Hueys provided medevac for casualties. Everyone relied on the Hueys for support.

When Craig managed to find a little down time on the ground, he sought solace in his hooch at the air base at Cu Chi. He soon acquired and set up an elaborate sound system with a quality reel-to-reel tape player. Jim Morrison and The Doors at the time were releasing a great deal of music, much of which reflected the turbulent times. Their powerful melancholy song The End, as well as Break On Through (To The Other Side), came out in January 1967. When The Music's Over came out in August 1967. In March 1968, just after Craig arrived in Vietnam, The Doors released the evocative song Unknown Soldier.

The Tet Offensive began just days before Craig Peterson landed in country. Fighting was intense from the moment he arrived at Cu Chi. 1968 would prove to be a violent year in Vietnam. Nearly 17,000 Americans lost their lives in 1968. The U.S. claimed to have killed more than 45,000 enemy soldiers, mostly Viet Cong, in the Tet offensive. Untold numbers, certainly large numbers, of civilians died.

Peterson's fellow soldiers soon came to respect him for his skill and courage. He was the kind of chopper pilot who would fly through a wall of lead to rescue Cav troopers or evacuate their wounded.

When Craig wrote home that it was cold in the cockpit, his brother Randy jumped into action and sent Craig a woolen Minnesota Vikings scarf as a present. The scarf was purple and white striped with a gold Vikings medallion on one end and fringes on both ends. Craig carried on the joke by wearing the scarf in flight. He soon decided that the scarf kept him safe from harm. Soldiers and their superstitions were not new. Craig’s fellow troopers would come to recognize the big guy in the chopper with the trademark grin and the Vikings scarf. Many did not know his name, but they knew him by his courage, his smile and the scarf around his neck.

Mini-Tet began May 1, just prior to the beginning of the rainy season. The mud made it difficult for motorized vehicles to go off-road. That emboldened the enemy to increase sniper fire, rocket fire, mines and even full-blown ambushes. It became common to take fire on convoy runs down highways.

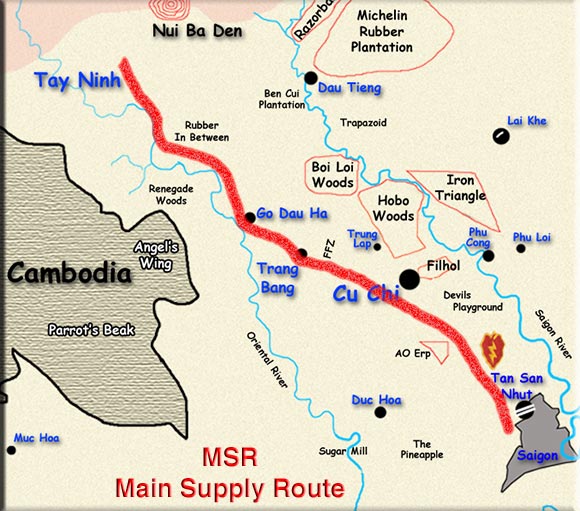

The Area of Operations for 3/4 Cav for August 1968 was Tay Ninh Province, northwest of Saigon. It was 89 kilometers (55 miles) from Saigon to Tay Ninh, the capital city of the province. The Cambodian border marked the northern, western and southwestern limits of Tay Ninh Province. The city of Tay Ninh was only 20 kilometers (12 miles) from Cambodia. Tay Ninh Combat Base was 5 kilometers (3 miles) west of the city of Tay Ninh and only 12 kilometers (7 miles) from the Cambodian border. There was a great deal of enemy activity in the area.

The Main Supply Route (MSR) from Saigon to Tay Ninh was 100 kilometers (65 miles) of dangerous road, which included Highway 1 and Highway 22. 3rd Squadron, 4th Cavalry was responsible for keeping the MSR open. The Vietnamese village of Go Dau Ha, directly south of Tay Ninh, was on the Cambodian border. The troopers of 3/4 Cav referred to Highway 22, the last leg of the journey to Tay Ninh, as Ambush Alley for good reason.

The VC routinely mined the MSR. It was necessary for engineers to sweep for mines every morning before opening the MSR for traffic. At the beginning of July 1968, someone came up with the idea to keep the road mine-free by running convoys all night.

The VC routinely mined the MSR. It was necessary for engineers to sweep for mines every morning before opening the MSR for traffic. At the beginning of July 1968, someone came up with the idea to keep the road mine-free by running convoys all night.

Captain Bill Shaffer, C Troop commander, sarcastically remarked to his troopers, "We are going to own the night." Everyone in Vietnam knew that the night belonged to Charlie; i.e., the Vietcong. Shaffer recalled, "My opinion was not asked for. It was mandated by Division headquarters ... An idea only and not much of one." Shaffer's opinion was that the concept " ... reeked of a lack of knowledge of combat." He knew too well that his troops and their armored vehicles would be "like ducks in a row" on the highway at night.

Captain Shaffer led C Troop, 3/4 Cav out of Tay Ninh on the night of July 3, 1968, escorting an empty six-truck convoy to Saigon. A Troop, 3/4 Cav was outposted along the road, one tank or armored personnel carrier vehicle every one hundred meters. Someone imagined that would add security. Most of the troopers knew too well that was not the case. C Troop's 2nd Platoon led the column. Captain Shaffer's command track followed the lead element. The six empty trucks followed. Then came 3rd platoon with Dwight Birdwell's tank in the lead. 1st Platoon brought up the rear. The night was pitch-black, perfect conditions for an ambush.

The column passed through Go Dau Ha and was approaching the deserted fire support base just beyond the village at 0130. Suddenly, fire-tails of rocket-propelled grenades (RPGs), one after another, lit up the night. Brilliant white flashes as they struck armored vehicles added to the spectacle. Streams of crisscrossing incoming green tracers raked the column. 2nd Platoon's lead tank took seven hits.

Everything happened almost instantaneously. The antennas on Captain Shaffer’s armored personnel carrier made his track a target The VC hit it with several RPGs. Shaffer recalled:

The first and second ones took me and the crew out. I saw all brilliant purple haze with sightless glazed eyes until coming out of my daze ... I could feel blood pulsing under my right hand. Uh, oh.

Shaffer's entire crew was dazed, momentarily blinded and hearing-impaired. As each recovered, he found himself immersed in the flashes and ear-splitting cacophony of an intense firefight. Ralph Ball, the track commander, was hit and his .50-cal machine gun was silent. APC Driver Frank Cuff, despite being wounded and stunned, fell back into the hull to open the back ramp and evacuate. At that moment, a third RPG hit the track. Cuff managed to find the handle and release the ramp. He dragged Captain Shaffer into the ditch for cover. All the lead vehicles were hit. Most were disabled.

1LT Dick Thomas saw Cuff drag Shaffer into the ditch and assumed the captain was dead. An RPG had just blown Thomas off his track. He climbed back in, grabbed a headset and called in for air support. A second RPG ripped through the hull and nearly severed Thomas' arm. Russ "Doc" Gearhart, the platoon's medic, was in a personnel carrier behind the command track. His hand was a bloody mess from the fragments of an RPG hit on his vehicle. He grabbed his medic's bag with his good hand and jumped off the burning vehicle. Gearhart scrambled to the aid of Thomas under the cover of the .50-cals. He put out the lieutenant's burning fatigues, secured a tourniquet and gave him a shot of morphine. Then he moved on to the next casualty. Doc Gearhart came upon Captain Shaffer in the ditch. He gave Shaffer some morphine and applied a wrap-around pressure bandage to the badly bleeding leg wound, which turned out to be a severed femoral artery. Shaffer needed a medevac out.

Warrant Officer Craig Peterson was flying empty and returning from another mission to his base at Cu Chi when he heard the radio traffic. He was over hours and was going to be in trouble if he responded to C Troop’s call for help. That did not deter him for a moment. The sky was pitch black and a trooper guided Peterson in with a handheld strobe. Peterson set down in rice paddy on the side of the road from the ambush. Frank and Doc carried Shaffer to the Huey. Peterson lifted off into the night with small arms fire continuing. As they flew off across the night sky, Doc offered Craig a fifth of whiskey for his purple-and-gold scarf. Peterson just smiled. Doc drank the bottle and tossed it out the door. Shaffer made it to 12th Evac at Cu Chi. Two-thirds of those with a severed femoral artery lose their leg. Bill Shaffer did not. They gave him five pints of blood before commencing surgery.

The Armed Services column in the St. Paul Dispatch of July 17, 1968 included a small notice:

Army Warrant Officer Craig L. Peterson, son of Mr. and Mrs. Raymond L. Peterson, 1865 Fairmount Ave., received the Air Medal for aerial support of Vietnam ground operations.

The Tet offensive in early 1968 and Mini-Tet in May were both costly to the North Vietnamese and Viet Cong in terms of lives. However, the impact in the United States, the recognition that the war might be far from over, made them major political victories for the insurgents. The NVA command, seeking another such victory, launched a third and final offensive in August. Historians know this as The Third Offensive.

During the Third Offensive, two divisions attacked the city of Tay Ninh in the oppressive heat of August. Their hope was that the afternoon heavy monsoon rains would prevent full utilization of American air power. The military objective was to capture the city. The political objective was to kill Americans. The fierce battle lasted from August 17 to August 27, 1968.

Among the combatants was PFC Gene Peters, the nineteen-year-old son of a Montana rancher. He rode into battle on Track 30, an APC (Armored Personnel Carrier), in A Troop, 3/4 Cavalry. Track 30 was the command track for 3rd Platoon. Lieutenant John D. Peterson, the platoon leader, was twenty years old. The track commander was twenty-nine-year-old Platoon Sergeant Richard Christy. Also aboard was PFC Delma “Doc” Phillips, the platoon medic.

At 9:30 in the morning on August 19, 1968, 3rd Squadron was four miles west of Tay Ninh City. The NVA & VC blew up a bridge on Highway 22, the main Saigon-to-Tay Ninh route. 3rd Squadron was moving along an alternate route, which was barely a raised trail (Hwy 26). Peters wrote:

We are hit from both sides in a horrific firefight of small arms and RPGs. Heavy fire from the ground, as well as the rubber trees up above us. We fight with all we have ... I am on the right rear of the PC behind the M60 machine gun. SGT Christy is behind the M50 machine gun in the center of the track in the 360-degree swivel turret. I am covering the 1 o'clock to the 5 o'clock position with the M60. TC Christy doing the same with the M50. We are covering only the right because the track in front of us is covering the left side of the road.

We are hit from both sides in a horrific firefight of small arms and RPGs. Heavy fire from the ground, as well as the rubber trees up above us. We fight with all we have ... I am on the right rear of the PC behind the M60 machine gun. SGT Christy is behind the M50 machine gun in the center of the track in the 360-degree swivel turret. I am covering the 1 o'clock to the 5 o'clock position with the M60. TC Christy doing the same with the M50. We are covering only the right because the track in front of us is covering the left side of the road.

The enemy fired from a myriad of "spider holes", concealed positions dug into the ground. Peters continues:

I see a ball of fire come out from under one of the spider holes. It's an RPG. It skips on the ground a few yards out and blows, throwing crap up at me, blowing me off the top of the PC into the hatch. I get right back up and return to firing my gun. I'm thinking, "Holy Cow, I've been hit, man." Then I realize I am having a hard time seeing. I am losing blood big time from my right calf.

AK-47 rounds hit Lt. Peterson and Christy in their arms. Christy cannot chamber rounds into his M50 so I jump to the top and do this for him. We have every weapon so hot that they cease to fire after a few bursts. I go back to fire my M60 until, each time, I see that Christy needs help again. We cover 180 degrees to our right side. My boot is full of blood.

Doc Phillips has us somewhat stable and taped up. Christy is very weak. He is hurting, his face a very pale white. He goes in and out of being coherent. Lt. Peterson, wounded in the upper arm, is holding his own. I am hurting, but have not lost it. I keep telling myself to not pass out. My face stings from the blast. There is shrapnel in my right arm. My right calf is taped up from knee down to the boot. Some guys run up to us and tell us someone is coming to take us up the road to the dust off. Others are there to help us. We are totally unaware of where the Medevac chopper is or how we get to it. All we know is we are supposed to be getting out of there.

All our tanks and personnel carriers are sitting on the road. We are not moving and we are under heavy fire. Staff Sergeant Pfost (known as "Frosty") is the TC on track A-35, an M48 Patton tank. Frosty takes it upon himself to come get us. He is in the front of our line of vehicles. His tank whirls around and rumbles back maybe a few hundred yards to our location. The road is jammed so he comes down the side of the road. Soldiers help us from our vehicle. We are taking heavy small arms fire and RPG fire. Christy and I hobble with our arms over the shoulders of a man on each side of us. The guys helping us interlock their fingers to form a step with their hands and boost us up onto the rear deck of the M48. Ernie Helton reaches down and pulls us up one at a time onto the back end of this beast. Meanwhile, bursts of AK-47 fire are all around and over us. I turn to my left and see this dink targeting me with his AK from under a brush pile. His rounds were hitting inches to the right of me. The M48 engine is under a grated cover in the back and it is hot as a stovetop. We are on our bellies and taking heavy fire! Helton throws out cases of C Rations to help protect us from shrapnel and small arms fire. The driver gasses the tank and we take off. I can barely hold on. Bullet after bullet ricochets off everything around us. It is a miracle we are not hit.

The tank is wide-open throttle and flying down the road toward the dustoff. I can't possibly describe the view. Everything is so battle-torn! The tank pulls up about a hundred yards or so from the chopper, which has dropped into a very hot landing zone. Waiting soldiers with stretchers rush us to the waiting medevac chopper! The pilot is throttling his bird, ready to leap.

The pilot was Warrant Officer Craig Peterson. His reputation for fearless flying to support his comrades was well established. Gene Peter's images of the experience remain as sharp as if it happened yesterday:

The dirt and the noise and whirlpool of rushing air are heavy. There are four bodies on the floor, covered with poncho liners. The sliding doors on both sides are open. There is no M60 machine gun at the door. Larry Wilkerson appears, running as best he can to the chopper with Doc Langford in a fireman carry. In a single motion, Wilkerson pushes Doc off his shoulders and into the small remaining space and runs back. We are instantly up in the air and pulling to the right. I grab on to anything I can find to hang on. Both side doors are open and we are taking small arms fire. I holler at Doc, but he does not answer. He is still. A rush of wind blows off the poncho liners and I see who is under them! 1SG John Veara, PFC Leonard Sexton, SGT Dwayne Kever and SGT Terry Hodges. Christy and I are the only ones alive besides the pilot and his one crewmember. Once up and into higher elevation, we leave behind the small arms fire. The crewman slams the door on the right side. We fly all the way to Tay Ninh with the left side door open.

Craig Peterson flew Gene Peters to small medical facility outside Tay Ninh. There were so many wounded that there were no beds. The docs evaluated Peters while he lay on the floor. He and the other wounded survived a mortar attack on the facility before being flown to the 12th Evac Hospital at Chu Chi very late into the night. They also lay on the floor at Chu Chi for some time. All the hospitals were full. The dead, the dying and the wounded were everywhere. Screams, cries and moans went on for hours.

Gene Peters later reflected:

Craig Peterson did this to save the wounded and retrieve the KIA'S numerous times throughout the Battle of Tay Ninh from August 19th through August 24! A Troop suffered 6 KIAs this day. He was an honorable man who put others' lives ahead of his own! I am one of many who credits Craig for doing just that for me ... My involvement with Craig and him lifting me out of that terrible situation is a very minute story of what Craig did during the battle for Tay Ninh ... Craig did this numerous times during the days of this battle ...

The relentless North Vietnamese offensive continued. FSB (Fire Support Base) Schofield, sixty miles northwest of Saigon near Dau Tieng, was within the domain of the 25th Infantry Division. On the night of August 24, 1968, a large enemy force attacked the base. The 25th Aviation Battalion routinely provided medical evacuation to the 3rd Squadron. But on this night, the battle so intense, that 25th Aviation command decided the landing zone was too hot. They would not allow their ships and crews to enter the combat zone. At the same time, there were many wounded in need of immediate medical attention. 3rd Squadron’s A Troop alone had 4 KIAs and 18 WIAs. They called on the squadron's own D Troop. CW2 Peterson answered the call.

Peterson knew that men on the ground needed him and that they were counting on him. He flew his Huey into the hot landing zone through the bright flashes and rips of light. Explosions shook the chopper. Peterson resisted jolts of fear as bullets ripped through the cockpit. Any moment, a shell could take out his rotor blade, sending his chopper spinning out of control and slamming into the ground. He touched down in a firestorm and men with stretchers scrambled toward him. In moments, the chopper was loaded with the wounded and the dying. He took the chopper up, through the firestorm and then finally took a long breath as he finally veered out of range of enemy fire. No chopper pilot ever knew how he got in and out of a hot zone. He took the first casualties to the base camp hospital at Dau Tieng then returned to FSB Schofield, despite having experienced the intensity of the firefight underway.

Peterson returned again and again to FSB Schofield. When the hospital at Dau Tieng reached capacity, he evacuated the wounded to the base hospital at Tay Ninh. When that hospital was full, he took the wounded to the 12th Evac Hospital at Cu Chi.

Gene Yonke was on the .50 caliber machine gun, firing away at the onrushing enemy. When the gun jammed, he scrambled out of the cupola to look for another weapon. A second or two later, an RPG hit the cupola. The back ramp was down and the blast blew Yonke out. Fragments hit him in the chest, shoulder and arm. The captain's track next to Yonke's took a hit from an RPG. The explosion ignited a LAW rocket strapped to the side of the track and the track burst into flames. The explosion wounded Yonke in the head and knocked him unconscious. When Yonke came to and sat up, the blood collected in the foam liner of his helmet ran down his back. Yonke remembered: "The only dustoff that night was a Centaur pilot ... Craig Peterson ... this guy was wearing a purple scarf, which is strange ... he made multiple extractions ... I was on about the 4th or 5th one out ... We flew into the 12th Evac Hospital at Cu Chi."

A Troop was comprised of 21 APCs and 9 tanks with a total complement of nearly two hundred men. Most of the armored vehicles were hit and only a handful of the troopers were uninjured. Gene Yonke wrote:

There was only one Delta Troop helicopter pilot assigned to the air that August night and it was our own Craig Peterson. Craig not only made the initial retrieval of dead and wounded at the fire support base, but even after experiencing first-hand the intensity of the battle and realizing that any subsequent attempts to land within the fire support base would pose a serious risk to his life as well as that of his crew, his bravery and selfless dedication to his fellow troopers showed through when he chose to repeatedly fly into the heat of battle to retrieve all of the dead and wounded who were brought to his chopper for evacuation.

If you were involved in that battle, then Craig either medevac’d you or one of your buddies and possibly saved your life. It’s estimated that Craig evacuated between 60 and 80 personnel from FSB Schofield, the actual number remains uncertain … Craig was an unassuming individual and always felt that he was ‘just doing his job’, but for many of us, him doing his job is the reason we’re still alive today.

There was talk for a time of Craig Peterson receiving the Medal of Honor. That did not happen nor did Craig receive any other awards for heroism during those battles. Unfortunately, and to the regret of many, Craig and so many other troopers did not receive the award recognition for actions that clearly were above and beyond the call to duty. In any case, these untold acts of heroism saved many lives and will not be forgotten.

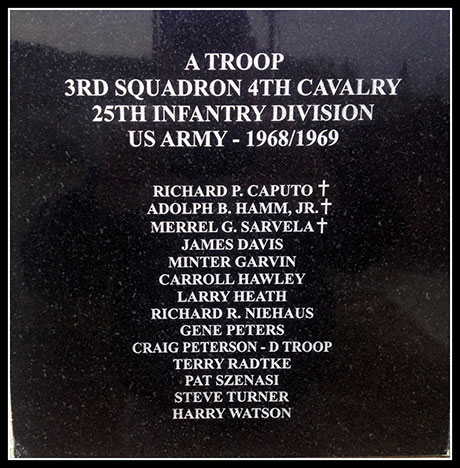

Thirteen troopers of A Troop, 3/4 Cavalry, most of them between nineteen and twenty-one years old, gave their lives to stop the VC and NVA in the Battle for Tay Ninh.

In November 1968, LTC Robert S. McGowan became the squadron commander. Captain Mel Moss, his A Troop Commander, described McGowan as:

... a West Pointer, was tall with short-cropped graying hair, wore glasses and had absolutely penetrating eyes. When he looked at you there was no question about to whom he was directing his attention. Around his neck he always wore a yellow silk scarf, the label of a member of an armor or cavalry unit. While everyone else wore jungle boots, Colonel McGowan wore only tankers' boots.

The colonel did not wait to settle into his job.

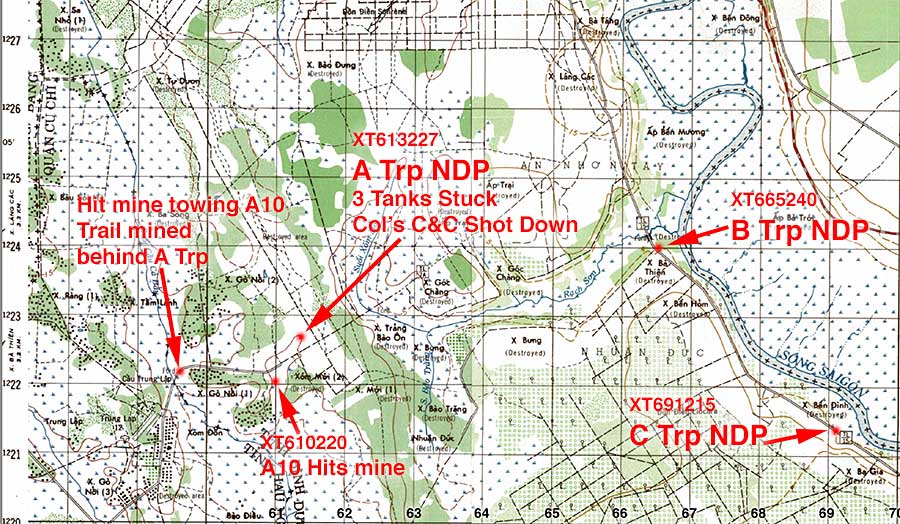

Colonel McGowan was anxious to get the squadron out and about and killing Charlie in large numbers. The colonel gave me a new mission ... to move north of the supply route and enter an area called the Ho Bo Woods. To reach our destination, we would have to travel up an ox cart road and through the remains of an old rubber plantation. The plan was to leave my tanks with another troop and make the move only with my APCs ... I didn't like having to leave my tanks ...

The wet season had just finished. Both sides knew well that renewed off-road operations would soon commence once the ground dried sufficiently to support massive armored vehicles. The Armored Cav personnel had some concerns that their vehicles might bog down in the mud. Nonetheless, like all good soldiers, they followed orders and moved out on their latest mission.

A Troop moved up the ox cart road on November 30, 1968; or, as Captain Moss described the advance, "into the hinterland". For a time, the column threaded its way down the trail. Tense soldiers eyed the surrounding terrain, their hands on their machine guns on the decks of the APCs. The only sound was that of the tracks of the armored vehicles. A loud explosion suddenly shattered the morning. A land mine blew the track off the troop's lead APC. The force of the blast ripped off the entire cupola and threw 1st Platoon Leader Lt. John Moore, Sergeant Carroll Hawley, the track commander, and SP4 Warren Yeagley fifty feet from the track. Small arms opened up on the column from the left flank. Captain Moss deployed his tracks with an "action left". Moss recalled:

We found nothing. We couldn't scare up the VC who detonated the mine ... It was very frustrating ... were toying with us ... the psychological impact on the crew and the entire troop was devastating.

Yeagley climbed back onto the track and pulled PFC Kurt Pearson out of the driver’s hatch. Pearson had a badly mangled foot. Other troopers found Sergeant Hawley in bad shape and in visible pain. A dustoff helicopter medevaced out Hawley and Pearson. Lt. Moore refused to leave his platoon and remained.

Captain Moss left one track with the disabled vehicle and proceeded into the Ho Bo Woods. "We moved slowly and deliberately ...". Small arms fire opened up on them from the front. It was late afternoon and Colonel McGowan radioed Moss to take his troop back to the disabled APC and form a night laager (a defensive circle with interior line) before darkness fell. The colonel sent up A Troop's tanks. The tracks made 180-degree turns and moved out. As they reached the assigned site, each track moved off the trail and took up a position. The laager would be fifty to seventy-five yards across with twenty-three armored vehicles in all, including the tanks. The tanks appeared, coming up the ox cart trail to join them.

As the first tank pulled off the trail, it broke through the crust and sank down to its sponson boxes. A second tank and third tank encountered the same results, sinking into the putrid muck. Moss re-arranged the laager and all was set for the night. All that is, except for the arrival of the CO. Moss wrote, "The nights in Vietnam seemed enormous. You almost felt the darkness and, except on moonlit nights, there was no light. It was pitch-black darkness." Once night fell, troopers remained in their vehicles.

Back at Cu Chi Base Camp, Warrant Officer Craig Peterson received orders to transport Colonel McGowan to A Troop's night laager position. It was Peterson's birthday. He was twenty-two years old, but that only mattered if he was "back home in the world". He might have felt some excitement when he realized he would be flying a brand-new Huey. The colonel, LT James Skiff, the colonel's S-3, and CSM Wilbur Duggins boarded and Peterson lifted off. A Troop's night laager was north of Trang Bang. Peterson knew well that the area was an enemy stronghold. It was business as usual.

Captain Moss awaited the colonel's arrival. From the south, off to the captain's left, he heard the whoop whoop of an incoming Huey. PSG Christy directed PFC Tim Verver to dismount his tank and operate a strobe light to direct the chopper in. Moss remembered: "Craig is floating that baby in, dropping, dropping ... and then it came ... an RPG!" WO Craig Peterson's Huey was ten feet off the ground when he felt the impact. "A ball of flame rushed past the cockpit. We knew it was time to abandon ship!" Moss stared in disbelief. "The fireball coming down. Everything goes into slow motion. An absolute cacophony of sound in slow motion." The entire laager responded by opening up, returning fire 360 degrees.

The two pilots, the two gunners and the three passengers all managed to escape unscathed from the ball of fire. The colonel told Peterson, "Nice landing!" And it was. Craig Peterson recalled, "When you're scared to hell, you can do some marvelous things and, at that moment, hell was looking really close." He did his job. Lt. Moore came over the troop frequency after what seemed forever and reported, "We got them. They are all ok." Everyone breathed a sigh of relief. The VC could not have made a more perfect shot into the fuel cell of Peterson's chopper. For Captain Mel Moss, after a terrible day that seemed to have gotten even worse, he did not have to account for seven lost lives. Captain Moss recalled:

Finally, the colonel made his way to my track and you could tell his adrenaline was running very high, but he was in good humor, laughing in his usual manner. As the colonel scrambled off his Huey, he tried to fire off his CAR-15, but the weapon jammed. He was a little embarrassed about that and laughed it off. CSM Duggins gave the colonel’s weapon to a trooper to have it cleaned. The troopers thought it was great to have the colonel in the midst of the firefight. Meanwhile, the squadron headquarters was calling to ask me if I could begin to reduce my volume of fire because we were causing real problems for the infantry FSB that was located down the road from us. I wasn't too interested in reducing any firing at that particular moment.

The firefight eventually ceased. Craig Peterson and his crew spent an uneasy night with A Troop in the laager. The morning light revealed that Craig's chopper was little more than rotor blades in a pile of ash and molten metal fragments. Craig and his crew flew out with Colonel McGowan in a chopper that arrived without incident. A Troop retrieved the tanks from the muck and headed back to Cu Chi for needed maintenance and a night off.

On December 2, just days later, Colonel McGowan directed Captain Moss to make a recon flight. The captain was to look for a site for a new FSB (fire support base) south of the MSR (main supply route) between Phuc Me and An Duc. His pilot for the recon flight was Centaur 63. Moss found himself looking at a smiling Craig Peterson. Moss recalled:

He had on that goofy scarf ... thanked me for getting his bird blown out of the sky. As we went up and through the recon, Craig made sure to not let me forget the incident.

Along the way, just for fun, WO Peterson had the captain take the stick for a few moments. It was just another day in Vietnam. Mel Moss commented, "It was very difficult to not remember Craig with his trademark smile and goofy scarf."

Craig Peterson received a promotion in rank to Chief Warrant Officer 2 (CW2) on January 30, 1969. His first tour of duty in Vietnam ended less than a month later on February 17, 1969. Craig’s younger brother Randy remembers being out with Craig when he was home on leave from the service. They drank a lot of beer and were sitting drunk in a restaurant. Four guys started picking on them. Someone called the police. They arrived and started checking IDs. The officer asked Craig what he did for a living. Craig replied, "I kill people." He proceeded to explain that he was back from Vietnam. The police officer went over to the other guys and told them that he did not think they should mess with the Peterson boys. That ended the incident.

Chief Peterson returned to Vietnam for a second tour, beginning on January 8, 1971. He served as a medevac pilot for the 54th Medical Detachment. He left Vietnam in August 1971 with the Air Medal with 14 Oak Leaf Clusters. There was talk of Peterson being put in for the Medal of Honor, but nothing came of it. No one could argue that the matter did not deserve consideration.

Craig rode home from California on a Triumph 750 bike with long-fork handlebars. He served in the reserves for another year. Later, Peterson rejoined the reserves for the camaraderie of veterans. Everyone liked him. His best friends acknowledged that Craig was a lot smarter than most people gave him credit for. A close friend of Craig’s, who served in the reserves with him, said Craig never talked about Vietnam. He did acknowledge privately that he went to Vietnam with the sense that he probably would not be coming back.

In 1976, Craig met Cheryl, whom he married a year later. She was to play an important role in his life, not only loving him, but by bringing peace into his life … with considerable effort on her part. Like many veterans, who experienced combat, Craig struggled with the memories of death & destruction and the related emotions. The question: "When were you in Vietnam?" answered "Just last night" fit Craig, as it did so many others. As Mel Moss said of combat veterans, "Those, who go into the belly of the beast, never come out the same."

The vast bureaucracy of the VA was never a personalized experience. They would ask Craig each time if he ever saw combat. He finally started carrying his DD Form 149 attachment, which certified that he accumulated 747 hours of combat in Vietnam. He drank a lot, although that solved nothing. At the end of 2004, Cheryl wrote a very long letter to the VA, describing Craig’s very clear symptoms of PTSD. That became an important move in the ultimate healing of the heart of Craig Peterson, the warrior.

Veterans often say that what they really missed about their war was the men with whom they served and bonded so deeply. They spent years trying to put the memories and emotions behind them and could not. Veterans began to discover the catharsis that came with reunions with their beloved comrades-in-arms. Gradually, over time, others heard of the benefits and joined the gatherings. Craig Peterson went to his Air Cav reunion in 2004. His daughter Holly accompanied him, as Cheryl was still working. There was a lot of joking around at the reunion. The A Troop veterans had a good laugh with Craig about the night he spent with them in the laager (after his chopper was shot down).

Bill Shaffer reminisced with Peterson at the reunion. Craig laughed when Shaffer asked him if he remembered Doc Gearhart's offer to trade him a bottle for his trademark Vikings scarf. Craig acknowledged that he got into a bit of trouble for diverting from his path to head down into the melee that night. He smiled and shrugged. That was Craig’s way. Some guys in Nam smoked weed as an act of defiance to Army discipline. Craig Peterson just did the right thing, even if it meant ignoring orders. As Bill Shaffer reflected, “... flying into an active firefight in pitch-black conditions is definitely above and beyond …”.

Cheryl never gave up on Craig and had a tremendous impact on him. He finally quit drinking in early 2006. About that time, he began attending group sessions at the VA. Cheryl recalled:

Julianne Bailey at the VA suggested that Craig should go to "the Group". Julianne and I talked about this and between the two of us we finally got him to go. He went to every meeting if he was in town and it made a big difference. One of the members even had heard his name before from a friend whom Craig saved in Vietnam in August 1968. The guy really talked up how Craig was a hero ... That really made Craig feel like he was worth something in the eyes of the other guys. It was wonderful to see ... He talked a lot about Vietnam with those guys. His nightmares subsided. He dreamt still, but he was no longer jumping out of bed to get under the bed or flailing in bed and accidentally hitting me. You never ever woke Craig by putting a hand on him. You grabbed him by the toe.

It took years for Craig to have the VA verify his PTSD. As Cheryl related of his disability, “He got it 2% at a time.” Many veterans went through a similar process. They found renewed camaraderie in their fight with government bureaucracy. Craig received 100% disability on January 10, 2008. Cheryl accompanied Craig and Holly for the 3rd Squadron reunion in early 2008 at Fort Mitchell in Kentucky, just across the river from Cincinnati.

Gene Peters always wondered who the pilot of his medevac chopper was. No one seemed to know. Gene Yonke introduced Gene to Craig Peterson at the 2008 reunion. It was an emotional reunion for both. Gene Peters recalled:

I shook his hand and thanked him for what he did for us that day. He brushed that off as to not being a big deal. I told him it is a big deal to me. I hold this man in the highest respect possible today. Every day of my life has a moment that I remember and wonder how and why I am still alive and I remember my medevac chopper pilot ... I have and always will be grateful to him for what he did for me and the other wounded and KIAs that day! He got us out ... No one would come in to that hot zone, but Craig. I perhaps would not be here today but for Craig. Many of us would not be. He saved many lives just by daring to come in when no one else would!

In October 2008, just months after the Cav reunion, Craig Peterson went into the VA for a knee replacement. He died of complications on October 18, 2008. Everyone was in shock. He was sixty-one years old. He was buried with military honors in section 26, gravesite 2283 in Fort Snelling National Cemetery. His comrades, like his family and friends, will not forget his service. Centaur 63, his call sign in Vietnam, is not on Peterson's gravestone. It seems that it should be.

In 2016, A Troop, 3rd Squadron, 4th Cavalry included Craig Peterson’s name on their unit plaque at the General George S. Patton Memorial Museum in California. They thought that highly of Craig and remembered his courage, even after all the years that had passed. The honor is clear as the name is recorded as “Craig Peterson – D Troop”. That is how much the Huey pilot with the crazy purple and gold scarf meant to the armored troopers. The man with the purple scarf Viking scarf and the big smile was a genuine hero.

In 2016, A Troop, 3rd Squadron, 4th Cavalry included Craig Peterson’s name on their unit plaque at the General George S. Patton Memorial Museum in California. They thought that highly of Craig and remembered his courage, even after all the years that had passed. The honor is clear as the name is recorded as “Craig Peterson – D Troop”. That is how much the Huey pilot with the crazy purple and gold scarf meant to the armored troopers. The man with the purple scarf Viking scarf and the big smile was a genuine hero.

Craig Peterson was proud of his service and very clear on his commitment. He wrote:

The 3rd Squadron, 4th U.S. Cavalry remains, even today, the second most highly decorated unit in the history of the United States Army and being the flight wing component of the unit, our D-Troop, the Centaur airships, were always on call, ready, willing and able to respond and supply all routine or emergency requests from our ground units at any and all times of the day or night.

***************

All names mentioned in the Article

Craig Peterson, Gene Yonke, Dwight Birdwell, Bill Schaffer, Ralph Ball, Frank Cuff, Dick Thomas, Russ "Doc" Gearhart, Gene Peters, John D. Peterson, Richard Christy, Delma "Doc" Phillips, "Frosty Pfost, Ernie Helton, Leonard Sexton, Dwayne Kever, Terry Hodges, Robert McGowan, Mel Moss, John Moore, Carrol Hawley, Warren Yeagley, Kurt Pearson, James Skiff, Wilber Duggins, Tim Verver, Julianne Bailey