Cambodian Sunset

Cambodian Sunset

Published in VHPA "Aviator" Magazine Issue 33-05 Sep/Oct 2015

A near miss with another aircraft is not on an aviator's wish list. We are even a little uneasy on crowded ramps and taxiways. This happened twice to Bob, once in training with an OH-23 Raven and again in Vietnam in a UH-1 Huey.

In 1958, during my Primary Helicopter transition training at Camp Walters, Texas, a spine chilling event occurred as I returned solo from the stage field after dark. I thought I was all eyes, scanning and alert. In that fraction of a second, as I was leaning forward to reach the radio for a channel change to the tower frequency, another OH-23 Raven passed below me from my right. It was so close; my flight path was disturbed by the turbulence from his rotor. There was a second-long flash of the inside of his dimly lit, green-glowing cockpit. He was also solo.

In 1958, during my Primary Helicopter transition training at Camp Walters, Texas, a spine chilling event occurred as I returned solo from the stage field after dark. I thought I was all eyes, scanning and alert. In that fraction of a second, as I was leaning forward to reach the radio for a channel change to the tower frequency, another OH-23 Raven passed below me from my right. It was so close; my flight path was disturbed by the turbulence from his rotor. There was a second-long flash of the inside of his dimly lit, green-glowing cockpit. He was also solo.

Path, time and altitude define an air warrior’s space.

Fate puts two in precisely the same place.

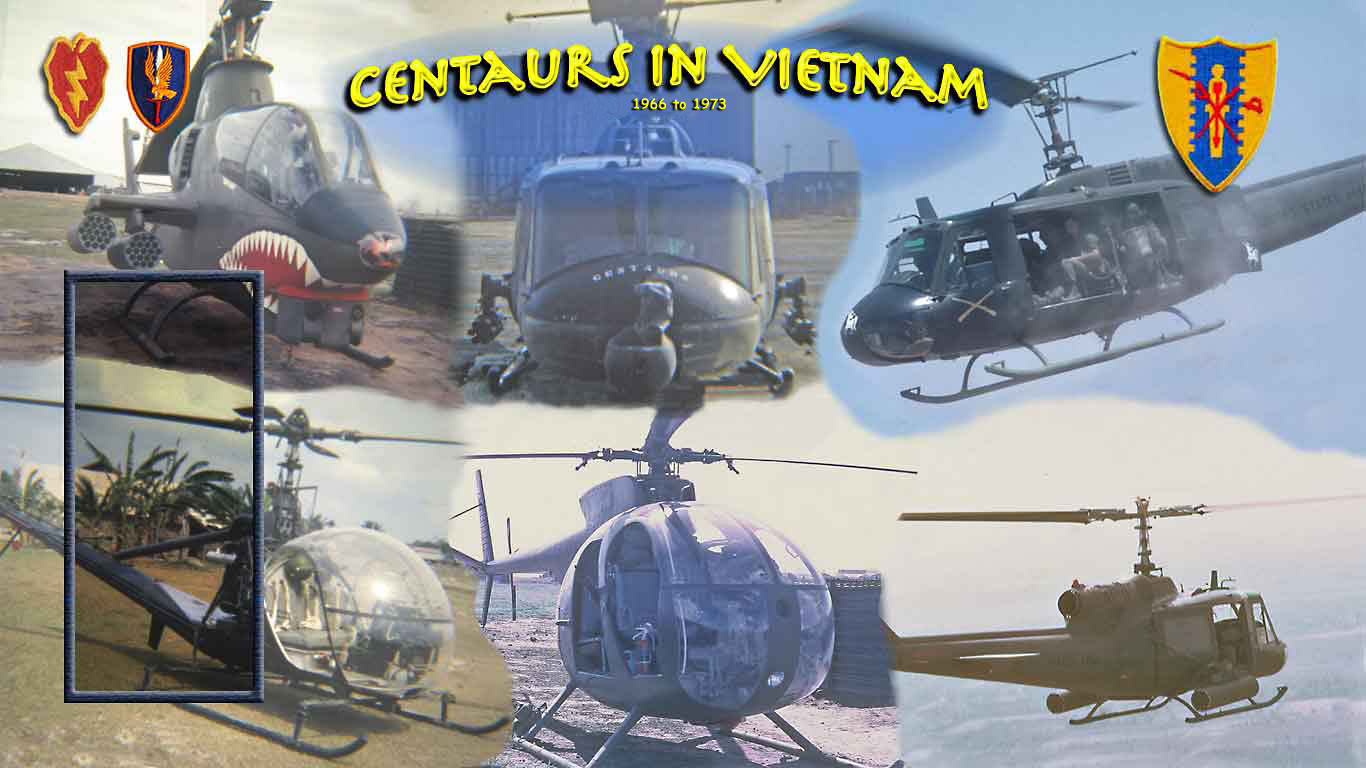

Eight years later, September 1966, Republic of South Vietnam this hair rising near miss experience occurred again. The missions were long range reconnaissance patrols (LRRP) in the border area of the Parrot's Beak. Our primary mission was information gathering; not raids and fire fights, but stealth if at all possible. My assignment: the operations officer of the Centaurs, D Troop (Air Cav), 3rd Squadron, 4th Cavalry Regiment.

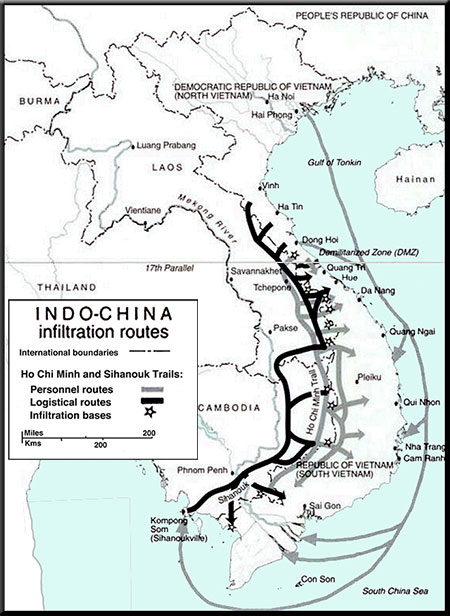

I planned the LRRP’s five-man-team mission insertions west of Tay Ninh, helicopter insertions into the heart of the Central Office South Vietnam (COSVIN). The area was near the southern end of the Ho Chi Minh Trail and the Sihanouk Trail passing from the south. COSVIN was the Supreme Viet Cong, (VC) Headquarters in South Vietnam. The North Vietnamese war of unification in South Vietnam was conducted from this headquarters.

I planned the LRRP’s five-man-team mission insertions west of Tay Ninh, helicopter insertions into the heart of the Central Office South Vietnam (COSVIN). The area was near the southern end of the Ho Chi Minh Trail and the Sihanouk Trail passing from the south. COSVIN was the Supreme Viet Cong, (VC) Headquarters in South Vietnam. The North Vietnamese war of unification in South Vietnam was conducted from this headquarters.

Although there were tens of thousands of VC involved, they ingeniously maintained a rather amorphous physical structure: a mobile command strategy: limited physical infrastructure, plus dispersion. From this large area they exercised political, logistical, and military command and control of military units up to division size and the total VC civilian infrastructure.

Materiel and supplies moved on both of these two trail networks in rather huge quantities. Quietly, and with much diplomatic consternation about Cambodia’s neutrality, cargo ships regularly unloaded at the port of Sihanoukville. Supply distribution involved thousands of packers resourcefully using cycles as carts, each carrying up to 200 pounds; also pack animals including elephants and standard military cargo vehicles. Tactical units of up to near division size were moved down from North Vietnam on the Ho Chi Minh Trail. We know all this now. During the fall of 1966, however, we were intent on detailing all this activity. Ultimately, we wished to find, fix and destroy the VC capability.

Leading up to the 25th infantry Division Augest1966 launch of Operation Attleboro, the 196th Infantry Brigade fought repeated probing battles to the west of their forward base at Tay Ninh, often identifying new enemy units. Linguists at the radio intercept station atop Nui Ba Den, The Black Virgin Mountain, monitored COSVIN and other VC radio traffic.

Heavy brigade combat patrols, the Air Force flying reconnaissance missions out of Thailand, and our own Centaur D Troop with attached LRRP focused their information gathering on the area. To insure communications westward, the LRRP had co-located a radio relay atop the Black Virgin Mountain manned by SP4 Dennis Hackamac and SP4 Bruce Hatfield. Except for the light scouts and a couple of fire teams, the majority of D Troop operations were out of the dusty forward base camp of the 196th Infantry Brigade. (Possibly the 3rd Bde at Dau Tieng)

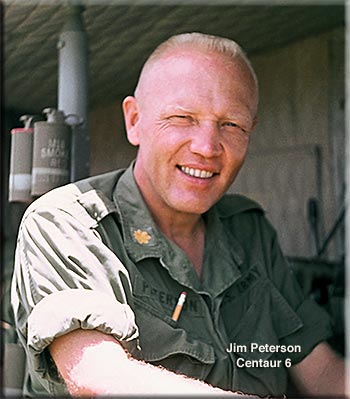

Over a period of a week, MAJ Jim Peterson, (Troop Commander), the LRRP team leaders and I in the command and control (C&C) Huey, conducted a detailed aerial reconnaissance for this September 1966 insertion. To circumvent attracting VC attention we always used single passes and avoided circling any possible insertion landing zones. Follow this up were treetop night missions, checking out sources of smoke, and night air sampling with a urine detector for possible locations of high concentrations. One small technicality: we could not discern concentrations of monkeys from VC.

Over a period of a week, MAJ Jim Peterson, (Troop Commander), the LRRP team leaders and I in the command and control (C&C) Huey, conducted a detailed aerial reconnaissance for this September 1966 insertion. To circumvent attracting VC attention we always used single passes and avoided circling any possible insertion landing zones. Follow this up were treetop night missions, checking out sources of smoke, and night air sampling with a urine detector for possible locations of high concentrations. One small technicality: we could not discern concentrations of monkeys from VC.

Current intelligence from the 25th Division G-2 was that VC activity was quiet during daylight, virtually no movement; then activity swelled after sundown. We assumed that there were lookouts and small patrols everywhere. After all, we were in their playground. The game was to watch and count the enemy without hostile contact. We were literally trying to place a firefly on an anthill without a fire fight.

D Troop’s briefing facility is the 196th Infantry Brigade’s tepid Tactical Operations Center (TOC), a sandbagged general purpose tent. The uneven scrap wood floor was constructed of used pallets and ammunition crates. I glean my aviation weather from local sources, reports available from far away Saigon and other posted data. We are also personally tuned from experience to the current and evolving weather patterns. The principals gather in the dim light. From my plastic map roll and the brigade’s current situation map, I review MAJ Peterson’s final tactical plan.

The Aerorifles and a light fire team will be on two minute standby at the forward base. No exact touchdown time is designated within the short window of dusk to darkness. The goal: safely land; allow the patrol to get oriented, positioned and then safe in the womb of darkness. MAJ Squires, the seemly perpetual insertion slick aircraft commander, in coordination with, the LRRP recon team leader, will make the final timing choice while airborne.The September 1966 evening air hangs heavy as I finish my routine final coordination briefing for the insertion.

The Aerorifles and a light fire team will be on two minute standby at the forward base. No exact touchdown time is designated within the short window of dusk to darkness. The goal: safely land; allow the patrol to get oriented, positioned and then safe in the womb of darkness. MAJ Squires, the seemly perpetual insertion slick aircraft commander, in coordination with, the LRRP recon team leader, will make the final timing choice while airborne.The September 1966 evening air hangs heavy as I finish my routine final coordination briefing for the insertion.

In Thailand, two small Asian countries away, an US Air Force RB-66 crew gathers at the air-conditioned Korate TRAF Base Squadron Operations for their crew brief. The RB-66’s first pass will be northward at an altitude of 1,000 feet just at dark.

In Thailand, two small Asian countries away, an US Air Force RB-66 crew gathers at the air-conditioned Korate TRAF Base Squadron Operations for their crew brief. The RB-66’s first pass will be northward at an altitude of 1,000 feet just at dark.

This evening’s LRRP team insertion incorporates before and after fake diversions with a single heavy scout gunship, a carefully selected series of low grass top passes and circling to act as a decoy and confusion creator. These maneuvers will be both prior to and after the actual insertion. None are light-hearted, little show-off acts as any or all could end in a serious escalating fire fight. After all, no one can sneak anywhere in a Huey with its incessant wop-wop-wop. We are taking advantage of this sound signature.

Our first reaction element, in case the insertion slick becomes disabled at the insertion point, is the maintenance and recovery Huey, affectionately called Stable Boy. It is prepared to pick up everyone with the cover of the two light fire teams present. If such an event occurred the Aero Rifle Platoon will be alerted and immediately go airborne with their additional light fire team.

In Thailand, the RB-66 aircraft commander signals to the ground support crewman that he has finished his start-engines. The copilot records the latest weather and sets the altimeter to the current barometric pressure for their immediate departure. This will be a routine electronic and imaging reconnaissance run up the Cambodian, Laotian and Vietnamese borders, monitoring the heavy traffic of the Sihanouk and Ho Chi Minh Trails.

The moment of insertion has been chosen by MAJ Mike Squires and LRRP team leader SP4 Jim Arp. Mike breaks radio silence with a terse, “30 Inbound.” In the C&C MAJ Peterson and I monitor the two light fire team leaders, “Roger.” Inbound now; Copilot CPT Gary Hatfield is wrapped in his chest protector, securely strapped into his armored seat. Gary takes a deep breath, settles, squints, focuses forward. He is light on the controls in case MAJ Squires is shot. On short final, four of the recon team slide to the open doors each positioning feet wide on the skids, steadied for a quick smooth exit.

Team leader Jim Arp crouches behind the two pilot’s armored seats focused forward, interpreting, evaluating the restricted panorama sweeping past just below on short final approach to his selected spot. All aboard are straining, seeking signs that their presence may be compromised to the VC. Mike Squires gently decelerates, hovering briefly, then holds steady, flattening the high grass. Door Gunner Herb Beasley focuses on the nearby tree line, at the ready with his M-60. Jim Arp, on Mike’s nod, calls out for the team to exit. Stable Boy is now three minutes out, heading inbound.

The five man team jump into the night. The first escorting gunship passes on the left to circle back. Each man is alert, focused, scanning his sector. Carefully, all slip into the shoulder high grass. Crew Chief SP4 James Pyburn calls, “Clear,” on the intercom. Seconds later, the five are alone with the diminishing sound of the departing Huey. The second escorting gunship passes along the tree line nearby and disappears along the low darkening horizon. In the distance the muted sounds of a decoy insertion is in progress. Observing no indication of hostile action Stable Boy breaks off on close final and climbs to clear the area. The initial insertion has created no hostile response on the ground.

The team is still, hearing only the sounds of their own breathing and that of the light evening breeze rustling the high grass of the Parrot's Beak of Cambodia. They wait near the Ho Chi Minh Trail, the supply route of the Vietnam Liberation Front. Initial success! The five men, Jim Arp, Mike Wood, Larry Blackman, Frank Robins, and Jerry Caldwell remain motionless and silent, then a cautious short 50 to 100 yards to pause again to monitor their surroundings.

The team is still, hearing only the sounds of their own breathing and that of the light evening breeze rustling the high grass of the Parrot's Beak of Cambodia. They wait near the Ho Chi Minh Trail, the supply route of the Vietnam Liberation Front. Initial success! The five men, Jim Arp, Mike Wood, Larry Blackman, Frank Robins, and Jerry Caldwell remain motionless and silent, then a cautious short 50 to 100 yards to pause again to monitor their surroundings.

We in the C&C take the small advantage of the glare of the Cambodian sunset holding to the west with the insertion fire teams. At the magical 1,000 feet on our altimeter, we fly a holding pattern, using the wavering signal from the distant Cu Chi low frequency marker beacon and the setting sun for orientation. MAJ Pete is peering into the deepening darkness, intent on the LRRP radio frequency.

There is no intercom chatter, just Huey sounds. As we circle all intently scan the insertion area for indications of possible contact, a tracer or the flash of a grenade.

Shortly, before the moon rises, SP4 Jim Arp stealthy moves his team to their surveillance location. With a radio mike covering the mouth, muted to near silence, a whispered radio contact is established. Centaur 6 (MAJ Pete) asks for an OK and receives the answer with the coded click of a mike transmit button. For all concerned, silence is good. Success!

Except for that crisp click code, absolutely no radio traffic will occur for a specific period unless they are compromised. We must assume that the VC is also listening to our frequency. I give MAJ Pete a thumb up and get an instrument cockpit blue-green smile in return.

The Artillery Liaison officer, crew chief and door gunner are silent with their own thoughts. There is really nothing to do except mind race about pleasant things, things that could go wrong, what to write home about or the last letter from home. After a period of combat seasoning, many just make sure that the intercom headset is on and actually relax. The whole crew loosens up, with an assuring peaceful feeling of success. To the peaceful mellow whine of the Huey’s turbine, I carefully level off at 1,000 feet, heading home toward the forward base at Tay Ninh.

It seems absolutely beautifully calm. Westward over Cambodia the spectacular sunset seems to be just for us.

We will return in three days to snatch up the LRRP team, and another effective reconnaissance cycle will have been completed. The thin horizon eastward toward Tay Ninh, and further Saigon, turns a deep purple with a dark blue night sky.

As the night darkens the jungle below, a large lighted aircraft cockpit flashes by about 30 feet to our front!

My God! So close, just below and in front of us! We just barely discerned the nose profile and the rudder of a RB-66 whisk by, nothing more. In that split second, our Huey jolts once as that big wing passes beneath us.

The night returns. I am spine-tinglingly, spellbound! MAJ Pete is stone silent, mesmerized, staring into the space of the vanished aircraft.

I yelled, “Did you see that! That large aircraft just passed in front of us!” I must have a heartbeat 200. Straining, squinting into the darkness to the left, hoping to see a fading image, it had disappeared into the night sky. “Jim, we were so close to that airplane that we could see the green glow of the cockpit lights. Did you see that lighted cockpit?” Silence is his answer.

I have reconstructed that split second many times. We were cruising level at that habitual even 1,000 on the altimeter; the airspeed was a steady 80 MPH. Our flight path was at a right angle facing the fuselage of the RB-66 which was headed toward our left. The mid-span of the jets left wing was about 10 to 15 feet below. The RB-66 rudder passed right in front of our cockpit! MAJ Peterson and I had an electrifying close call, probably a near death experience. The three troopers in the back were oblivious of our harrowing experience. That night there was little intercom chatter during our return to Tay Ninh.

Path, time and altitude define an air warrior’s space.

Fate put two in precisely the same place.

Copyright Nov 2013 Robert L. Graham