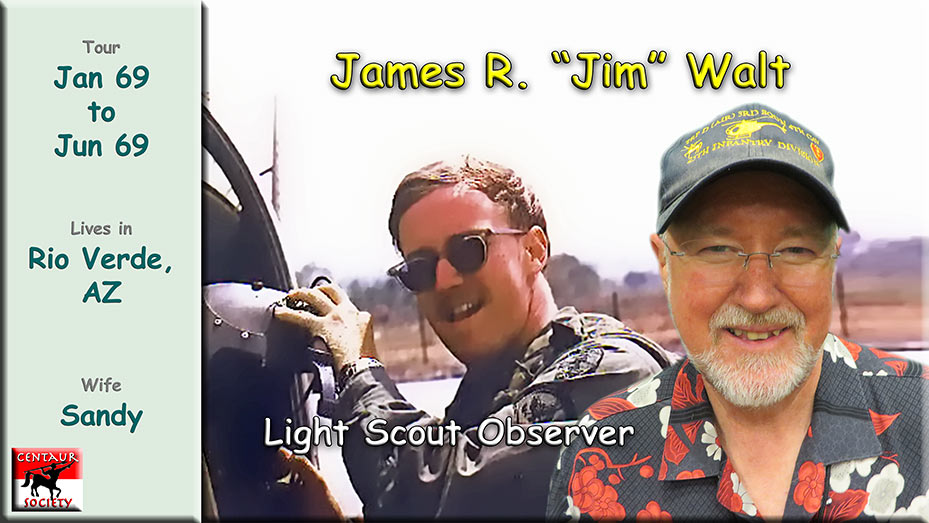

Jim Walt LOH Scout - 1967 - 1970

An Interview with James Robert Walt

by Vail Jenkins, Cactus Shadows High School

.....................................................................................................................................................................................

You Were Worth It

You Were Worth It

Mr. Jim Walt was born on June 12, 1947, into a military family. His family’s service was a point of pride in Mr. Walt’s young life—his paternal grandfather served in World War I and World War II, his father served in World War II as a Merchant Marine Officer, and his mother’s brother served in World War II. Not only did his family have a sense of patriotism, but growing up in the ‘50s and early ‘60s, patriotic views were the norm, and a common assumption was that all young men served their country when called.

Mr. Walt graduated from high school in 1965 and began college in 1966. During this time, he and his peers discussed whether the war should be supported. He was never truly anti-war, and assumed he would have to serve. In April of 1967, he received his draft notice. To receive more assignment options in the military, he decided to volunteer, increasing his military commitment from two years to three years. One MOS (Military Occupational Specialty) available to him was artillery surveying. He signed up as an artillery surveyor, which is a role in a team that is assigned to survey an artillery battery to their exact placement by longitude and latitude to help determine precisely and accurately where to fire the guns.

Before he could train for his new job he had to get through boot camp. Mr. Walt attended basic training at Fort Lewis, Washington, in June 1967. His time at Fort Lewis was miserable due to how hot it was. Over 300,000-plus men were being trained at the fort due to the high casualties (sometimes over 500 a week) in Vietnam. Once he got out of basic training he moved on to Advanced Infantry Training (AIT) for training in his new job as an artillery surveyor. He and his other peers thought and hoped that they might get sent to Germany, but almost everybody in his class ended up being sent to Vietnam.

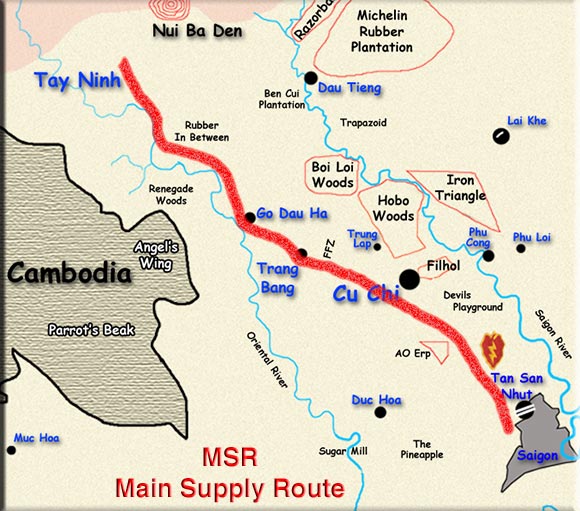

He arrived at Tan Son Nhut airport in Saigon, Vietnam, on December 4, 1967. As soon as they opened the aircraft door, the heavy humid air and foreign smell of fish sauce assaulted his senses. He was quickly sent through jungle school to help learn a little about what it would be like and what to do, but because his MOS was not combat, he did not go through the in-depth combat training many others received. After he finished jungle school he was sent to Tay Ninh, northwest of Saigon near the Cambodian border, where he was assigned as a private to the 7/11 Artillery Regiment, 25th Division. After a week in camp, he was sent out on his first survey job on December 19.

He arrived at Tan Son Nhut airport in Saigon, Vietnam, on December 4, 1967. As soon as they opened the aircraft door, the heavy humid air and foreign smell of fish sauce assaulted his senses. He was quickly sent through jungle school to help learn a little about what it would be like and what to do, but because his MOS was not combat, he did not go through the in-depth combat training many others received. After he finished jungle school he was sent to Tay Ninh, northwest of Saigon near the Cambodian border, where he was assigned as a private to the 7/11 Artillery Regiment, 25th Division. After a week in camp, he was sent out on his first survey job on December 19.

Mr. Walt and three others were flown out late in the afternoon to a small temporary fire support base (FSB) called FSB Beauregard near Bo Tuc, which is very close to the Cambodian border. While there, they surveyed from an old French road intersection back to the fire support base. However, because they got back into the small FSB camp late in the day, they didn’t have time to build a bunker for all four of the survey crew. The survey chief talked to the spotlight crew about sharing the spotlight crew’s two-person bunker. They all hoped that 2 they wouldn’t get hit that night because they would need to fit all six of them into the bunker quickly

At 2:00 in the morning, the mortars started coming in fast, causing them all to dive for the bunker. Because Pvt. Walt was close to the entrance, he was one of the first ones in the bunker. He moved to the back-left side and sat in the fetal position so the other men could fit in. The FSB was quickly overrun by NVA infantry and sappers attempting to destroy the guns and ammunition with small explosives and spiking the howitzers or throwing a grenade down the barrel of them. A few guns continued to fire, shooting “beehive” rounds leveled at the NVA. Each beehive round is packed with hundreds of small metal darts called flechettes and can have devastating bloody effects on enemy ground troops. The spotlight crew’s jeep was parked directly outside the entrance to the searchlight crew’s bunker. It caught fire, along with almost everything else in the camp. This not only made it very hard for the men in the bunker to breathe, but they were extremely worried about the jeep’s gas tank exploding and flaming gas flowing into the bunker. All around the camp, 105 mm shells had been scattered because of the sapper’s explosions. They were being heated up so much by the fire that some were detonating. Exploding grenades and 105 shells, along with the sound of small arms fire, filled the night. NVA were going back or forth from Cu Chi to Tay Ninh running through the camp, at times running directly over the small searchlight crew’s bunker.

Through the tumult one of the men said they needed more air, and some ventilation in their bunker because of all the smoke. One man told Pvt. Walt to pull out a sandbag on his side to create cross ventilation. As he did so, a 105 mm shell that had been resting on that particular sandbag fell slightly through the new air hole, its pointed end aimed directly at Pvt. Walt’s face. He quickly took an M16 rifle and very gently pushed the so-far unexploded shell as far as he could away from the bunker before returning the sandbag. A minute or two after he put the bag back the flames scorching the bunker sandbag liners and any other flammable objects caused the shell to explode. Amazingly and luckily, all the men in the bunker survived the four-hour battle with only the spotlight chief being injured from exploding shrapnel.

Earlier in the evening, Pvt. Walt had discovered that the spotlight sergeant happened to be just one year ahead of Pvt. Walt at the same high school he went to. The strange reunion was cut short when the spotlight sergeant was medevacked out the next morning. Pvt. Walt never saw him again. Soon after the injured were evacuated, Pvt. Walt and the others were flown back to their main base in Tay Ninh. Pvt. Walt was soon after stationed at a bigger FSB base called Katum, right on the Cambodian border. This was just before the infamous Tet Offensive that began on 30 January 1968 and continued into February.

The route the Northern Vietnamese Army took to the Saigon area went around Katum, silently bypassing them. The fact that a large enemy force could secretly be so close was not nearly as terrifying as the battles that were soon to come. It was the bloody battles of the Tet Offensive that turned around the opinion of the war in Vietnam.

The route the Northern Vietnamese Army took to the Saigon area went around Katum, silently bypassing them. The fact that a large enemy force could secretly be so close was not nearly as terrifying as the battles that were soon to come. It was the bloody battles of the Tet Offensive that turned around the opinion of the war in Vietnam.

On Feb. 13, 1968, Mr. Walt was promoted to Specialist 4 (Spec 4, the same rank as a corporal). In May of 1968, Spec 4 Walt and the rest of the survey crew got an emergency order. His unit would go out with medics to provide care to local villagers to go to FSB Maury, a fire support base halfway between Saigon and Cu Chi. The base had 155 self-propelled howitzers (artillery on a tank-like vehicle), and 105 artillery howitzers. They were trucked down to help serve as extra support due to the base being hit frequently during the previous week. On May 19 the infantry unit that typically defended the base perimeter was ambushed while patrolling outside the base. They could not disengage to return to the base. Spec 4 Walt and the rest of the survey crew were ordered to defend the perimeter. A few APCs (armor personnel carriers) were driven into quickly bulldozed holes on the perimeter line. Some of the APCs had .50 caliber machine guns mounted on top of them. Spec 4 Walt was not an infantryman. It was not something he was well trained for. Walt and the survey crew were positioned along the perimeter line behind a small rice paddy berm at approximately every 30 yards. At about 2 a.m. the base was attacked. A large NVA unit had planned the ambush of the infantry unit to keep it from being able to help defend the FSB. And now they were attacking the FSB with mortars, rockets, large-caliber machine guns and small arms fire. Spec 4 Walt’s M16 jammed, leaving him without a functioning weapon. He crawled about 30 yards to get to one of the APCs, where two others from his survey squad, Spec 5 Michael Brewer and a private named Pete, joined him. 3 Once they got to the APC, Mr. Walt positioned himself outside and behind one of the APC’s rear deck walls. He was assigned to watch the area to his side of the APC

The NVA started firing RPGs (Rocket Propelled Grenades, similar to bazookas) at the APC. An RPG round can penetrate the armor of an APC. Over the course of the 3-4 hour attack, the APC was hit by RPGs six or seven times, killing three soldiers inside the vehicle, and seriously wounding the rest. One of the soldiers killed was Spec 5 Michael Brewer, the survey crew chief. Spec 4 Walt was saved from serious wounds because he was outside the APC enclosure and behind a heavy partition of the APCs framework. By this time, all of the soldier’s weapons had jammed or been destroyed. Mr. Walt still had some grenades that he could throw. At one point in the battle Spec 4 Walt observed an NVA soldier that had proceeded about 25 yards past the APC into the FSB interior. In the reflected light of the fires from the center of the destroyed FSB, Spec 4 Walt clearly saw that the soldier was armed with a flamethrower. The awareness of this man and his weapon was one of the scariest sights he had ever experienced. He quickly threw a grenade at the soldier and ducked down. When he briefly looked up again the soldier was no longer visible. Spec 4 Walt assumed he had been killed or seriously injured. Eventually, after receiving needed air and gunship support, the battle ended. Sadly, Spec 5 Michael Brewer had been killed by an RPG, and Pvt. Pete was seriously injured. Mr. Walt was also hit by a piece of shrapnel in his hip. The battle destruction that night eventually changed the way that fire support bases and defensive systems were prepared and set up.

Spec 4 Walt was left in a mild state of shock for approximately a month. He found himself in a constant state of hypervigilance. He spent less time in the field, doing more administrative work. Because he had been an architectural student in college, he was skilled in mechanical ink lettering. He began doing a lot 4 of graphic design work for the unit commander. This skill earned him a Bronze Star for meritorious service. Spec 4 Walt was promoted to the rank of Spec 5 on September 21, 1968. Spec 5 Walt ended his regularly scheduled tour in Vietnam in early December.

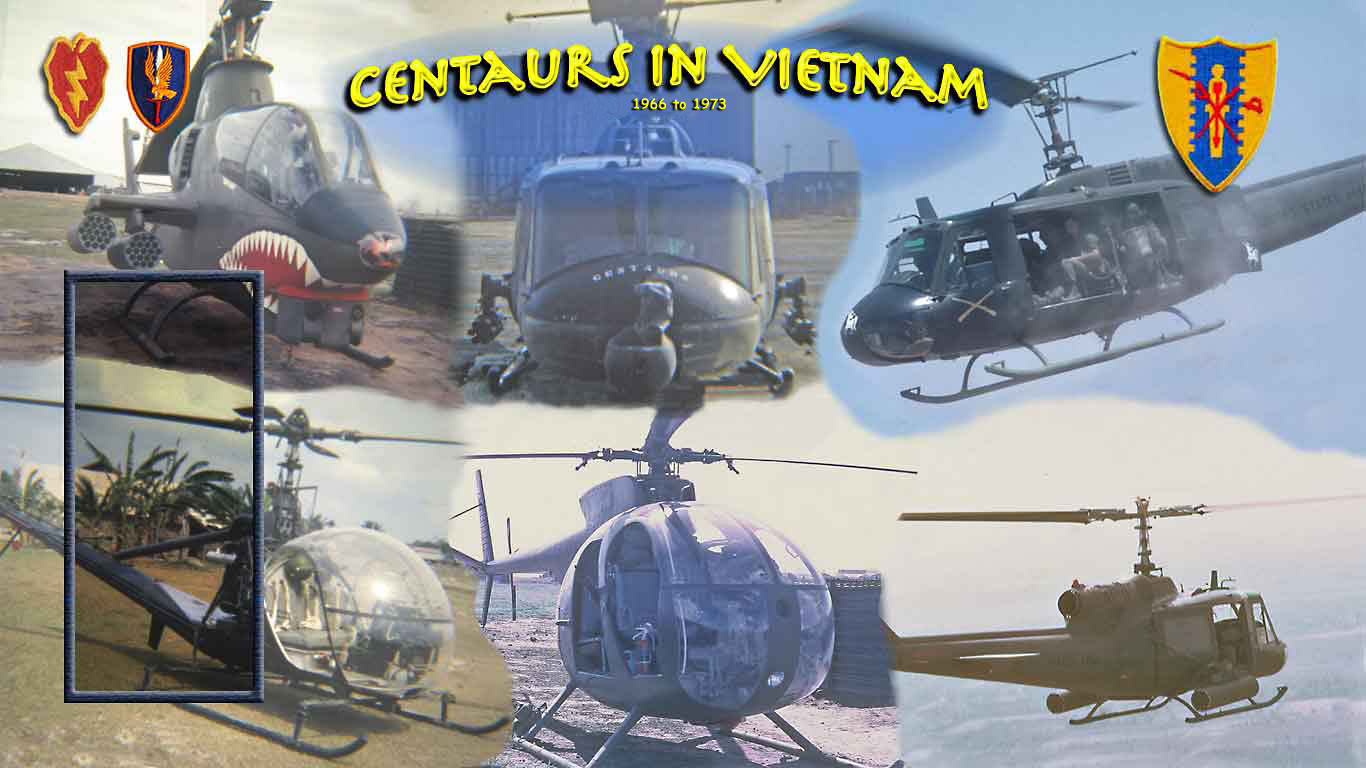

Just prior to departing Vietnam, on a visit to a friend at the 25th Division’s main base in Cu Chi, he found himself chatting with crewmen from the D Trp 3/4 CAV Light Scouts unit. D Trp 3/4 Cav was an air cavalry helicopter unit. Their job was to scout from the air the areas of operation for the armored ground troops of 3/4 Cav. Spec 5 Walt was particularly interested in the OH-6 Cayuse helicopter, known as the “Loach” (Light Observation Helicopter). The Loach was designed to be light, quick, and agile, and paired with a Cobra gunship (an attack helicopter) they were known as Hunter/Killer Teams. The D Trp Light Scouts NCOs talked about how exciting and fun it was being able to fly in the left front seat of the helicopter. Spec 5 Walt had always wanted to fly. They told him that the pilots would actually teach their NCO observers how to fly (in case the pilots got hurt or killed). This was all unofficial and winked at by command because NCOs were absolutely not supposed to fly. Oddly, they convinced him he should volunteer for a second tour.

Spec 5 Walt only has a hypothesis as to why he was okay with volunteering again. It was certainly not foreseen given his repeated near-death experiences over the last year. One hypothesis was the letter he received on Christmas Day 1967 at the remote Katum FSB from his girlfriend of two years. She called off their engagement. He had been quite devastated by that. He initially blamed his volunteering for a second tour on that break-up, with the strange thought that if he got hurt, she would feel bad. But he never fully believed that reason. Many years later, he realized it was because of something far more profound.

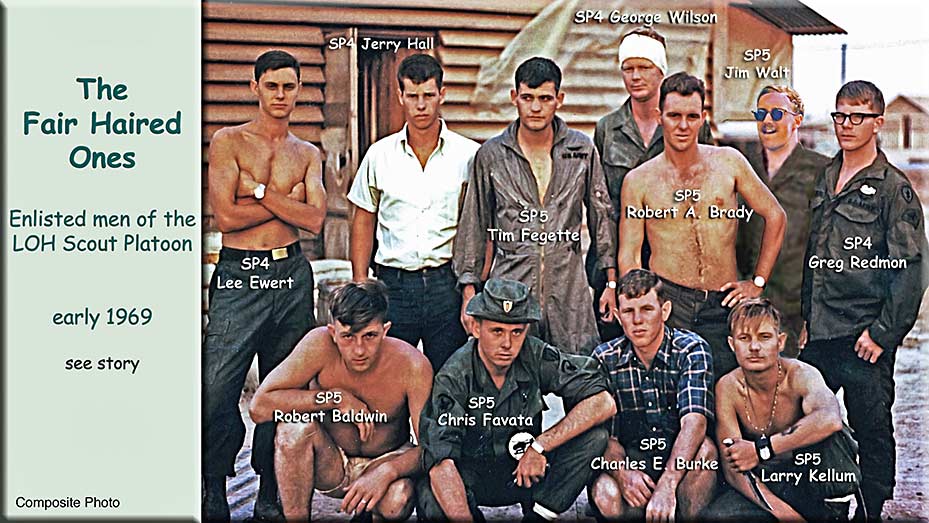

After the FSB Maury battle in May, as they were taking the wounded out the morning Fair Haired Ones 3/4 Cav early ‘69 - The Light Scouts crew, including all observers or crew chiefs after, he notified the rescue teams that he had been wounded. He had received a small injury in his hip from flying shrapnel. However, he wasn’t nearly as wounded as many of the others. He was aware that his injury was minimal compared to others. He also viscerally felt he needed to get out of that place. He would soon regretfully convince himself that in the fearful aftershock of the battle he had abandoned his duties. He had been a coward. It did not occur to him that rationally; his decimated survey crew would have returned later that day to Tay Ninh anyway. He was never questioned by anyone about being on the earlier evacuating helicopters taking the wounded back to the base at Tay Ninh. No one ever challenged him about any of it. Regardless, he never fully forgave himself for doing this. He realized years later that he volunteered for a second tour to prove to himself that he was not a coward.

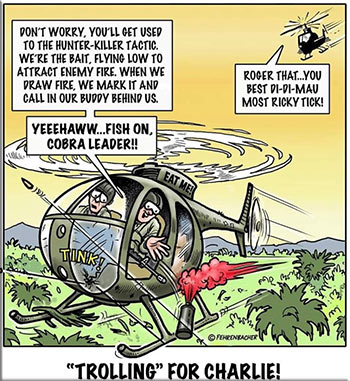

Spec 5 Walt went home on a 30-day leave. He did not tell his family he was going back to Vietnam until the day before he returned to duty. Spec 5 Walt returned to Vietnam for his second tour as an observer in Hunter/Killer teams in 3/4 CAV.  As an Observer in Loaches he flew in the front left seat, the helicopter flying very, very low and extremely fast, at bushtop levels. The faster and lower you flew, the less of a target you became. They were paired with a Cobra gunship. Once they arrived at their area of operation, the Loach would spiral down quickly so they could get to the low, safer level of about 10-50 feet. The Cobra would stay at about 1200 feet, circling and watching over the Loach. Spec 5 Walt’s job as an observer was to watch out for any unusual activity. If they drew any fire or saw enemy activity they relayed that information to the Cobra. The Cobra would then place their far superior firepower on the target. Loaches were the Hunters and the Cobras were the Killers. The Loach was the bait. The Cobra pilots called it “trolling.” This did not stop most Loach pilots from having a “gung ho” military mentality. They wanted to rack up body count, so many times Loaches would engage in full combat firefights. Loaches were always armed, just not nearly as heavily as the Cobras. The observer 5 flew in the left front seat, the crew chief in the rear right seat. The crew chief would have an M60 machine gun and a variety of grenades of different kinds. The observer would have an M16 or M60. When they found a bunker or anything else enemy-related, the observer would throw a smoke grenade on the position to locate it for the Cobra. Not uncommonly, the crew chief would throw fragmentation grenades at the targets. Like some of the pilots, some of the crew chiefs had a killer mentality.

As an Observer in Loaches he flew in the front left seat, the helicopter flying very, very low and extremely fast, at bushtop levels. The faster and lower you flew, the less of a target you became. They were paired with a Cobra gunship. Once they arrived at their area of operation, the Loach would spiral down quickly so they could get to the low, safer level of about 10-50 feet. The Cobra would stay at about 1200 feet, circling and watching over the Loach. Spec 5 Walt’s job as an observer was to watch out for any unusual activity. If they drew any fire or saw enemy activity they relayed that information to the Cobra. The Cobra would then place their far superior firepower on the target. Loaches were the Hunters and the Cobras were the Killers. The Loach was the bait. The Cobra pilots called it “trolling.” This did not stop most Loach pilots from having a “gung ho” military mentality. They wanted to rack up body count, so many times Loaches would engage in full combat firefights. Loaches were always armed, just not nearly as heavily as the Cobras. The observer 5 flew in the left front seat, the crew chief in the rear right seat. The crew chief would have an M60 machine gun and a variety of grenades of different kinds. The observer would have an M16 or M60. When they found a bunker or anything else enemy-related, the observer would throw a smoke grenade on the position to locate it for the Cobra. Not uncommonly, the crew chief would throw fragmentation grenades at the targets. Like some of the pilots, some of the crew chiefs had a killer mentality.

One crew chief was an ornery, skinny Texan named Iggy who decided one day while doing an after-action report at a fire support base that had been hit the night before, that they should land to collect souvenirs from the dead bodies on a battlefield. He proceeded to collect some AK-47s, and other items.

One time the team was patrolling in a free-fire zone, which meant that anybody seen was classified as an enemy combatant. That day the Loach had a mini-gun mounted. A mini- gun is a six-barreled machine gun that can fire up to 4000 rounds per minute. The crew chief spotted a man hiding behind a tree. The pilot maneuvered to be able to use the mini-gun and cut the man in half with the withering machine gun fire. Flying at high speeds at low levels brought high risks. During the Vietnam War almost 1000 OH-6 helicopters were lost to combat. Many, many more were repeatedly riddled with bullet holes from small arms gunfire. The losses were primarily due to the helicopter’s role, which required flying at such low altitudes and drawing enemy fire to locate targets. This made the OH-6 highly vulnerable to small arms fire, anti-aircraft weapons, and accidents in the sometimes triple canopy jungle terrain. Those who flew in Loaches knew that it wasn’t a matter of if they would crash, but when they would crash. Fortunately, because of a purposely designed rugged triangular roll cage that made up the main body, the Loach is one of the most crash-survivable helicopters.

Spec 5 Walt spectacularly crashed just once. On April 25, 1969, his crew was in an area called Loach Alley, named after the many Loaches that got shot down there. They were patrolling about a mile or two in front of A Troop, an armored tank and APC infantry unit. The crew chief that day was a temporary named Spec 5 John Dobash. Spec Dobash usually worked on Cobras. However, he wanted flying hours so he could receive flight pay. And, he really wanted to be in the middle of the action. They spotted an enemy bunker and Spec 5 Dobash started throwing grenades at it. He kept missing, so the pilot, 1st Lt. Marty Jenkins, decided to fly back around to try to hit it accurately. Coming around a third time, an explosion in the helicopter floor under Spec 5 Dobash and exploded. John was blown out the helicopter. Both of his legs were severed by the explosion. Lt. Jenkins and Spec 5 Walt crashed and rolled over perhaps 4-5 times in the stiff reinforced cage of the Loach.

Everything was on fire because the explosion had punctured the fuel tank. When they came to a stop, Spec 5 Walt yanked his seat belt off and scrambled out through the shattered front bubble window of the aircraft. Miraculously, the only injury he had was a small burn on his finger. Lt. Jenkins was severely burned on his head, shoulders, and back as the fire raged and had broken his leg in the crash. Spec 5 Walt was a few feet away from the crash when he heard Lt. Jenkins yell, “I can’t get out!” The fire that now completely engulfed the Loach was heating up all the ammunition, creating what is called “cooking off ” their munitions. Soon the white phosphorus and fragmentation grenades would be set off as well. Spec 5 Walt ran back and got to Lt. Jenkins while he was still trying to get his belt off. They released the belt and Spec 5 Walt pulled Lt. Jenkins out, and reverse fireman-carried him about 30 feet away before some of the grenades exploded. They were knocked over by the blast but were fortunately unharmed from that blast.

the belt and Spec 5 Walt pulled Lt. Jenkins out, and reverse fireman-carried him about 30 feet away before some of the grenades exploded. They were knocked over by the blast but were fortunately unharmed from that blast.

Joe Kline Aviation Art - Paper Tiger - a painting Jim had commissioned of their loach that crashed on Apr 25, ‘69

The Cobra gunship (pilot Tom Dooling) came down to observe the damage and saw Spec 5 Walt waving to them. They landed and the co-pilot got out to help Walt with Lt. Jenkins.

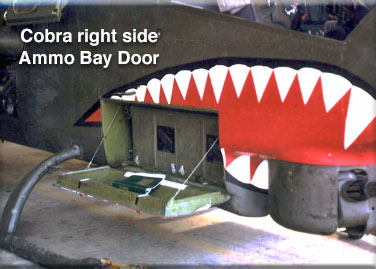

The Cobra was only a two-person ship. To be able to fly the Loach crew back to receive medical attention, they dropped down two small ammo access doors on the side of the Cobra, placing Lt. Jenkins on one side and Spec 5 Walt on the other. However, the Cobra was now grossly overweight and could not lift straight up and out. As the Cobra tried to lift out, it moved from side to side, while going up a bit and then down onto large bushes and small trees. The access doors were hinged on the bottom and would start to lever up and crush the two outriders.

The Cobra was only a two-person ship. To be able to fly the Loach crew back to receive medical attention, they dropped down two small ammo access doors on the side of the Cobra, placing Lt. Jenkins on one side and Spec 5 Walt on the other. However, the Cobra was now grossly overweight and could not lift straight up and out. As the Cobra tried to lift out, it moved from side to side, while going up a bit and then down onto large bushes and small trees. The access doors were hinged on the bottom and would start to lever up and crush the two outriders.

The Cobra pilot finally found a clear space and landed again. They took Lt. Jenkins and Spec 5 Walt off the access doors, and then the Cobra pilot lifted directly over the crew and fired all the Cobra rockets while turning 360 degrees.

They finally got everyone aboard and headed back to land at the 25th EVAC pad at Cu Chi. No Cobra had ever landed at the pad before, so many of the medical personnel ran out to see the Cobra land and take pictures. By pulling him from the burning and blowing up Loach and saving his life, Lt. Jenkins put Spec 5 Walt’s name in for the Medal of Honor. Spec 5 Walt thought that was far too much for his deed, and suggested that be changed. He instead received the Silver Star, the nation’s third-highest medal of valor.

Not only did he manage to save his pilot, but at a deeper level Spec 5 Walt felt that he finally redeemed himself from his doubts of May 1968. Spec 5 Walt ended his second tour of duty in Vietnam in July 1969. He had time left 7 in the service before his discharge, so he was assigned as an instructor at the Army Artillery Survey School in Fort Sill, Oklahoma. It is where he had originally trained to be a surveyor. Even though he wanted to be an instructor at the Helicopter Observer School, military actions had begun to slow down in Vietnam, and they had fewer needs for observers.

Spec 5 Walt was finally discharged in March 1970. Luckily, no strangers spat on him or called him a baby killer when he returned home, as many of his friends and colleagues had been. Because of his experiences in Vietnam he became anti-war after leaving the service. He went back to college at California State University Sacramento, receiving his BA and MA. He became a marriage and family therapist, and later, a professor of marriage and family therapy for 27 years. He met his future wife Sandy when he was 37. They married two years later and gave birth to a daughter in 1987.

For many years after, Mr. Walt did not like to think or talk about his time in the service. He did try to volunteer to help soldiers with PTSD at a local veterans’ service center but was put off by how easily soldiers were assumed to have PTSD just because they had experienced traumatic events. Even though Mr. Walt saw all the terrible things he did, he never got PTSD. How was that, he wondered?

He began attending his old D Trp 3/4 Cav unit’s reunions in the early 2000s. One evening, after many drinks but much more sober conversation, he discovered that four of the six vets from his Light Scouts unit were on full disability for PTSD. And they were trying to convince the other veteran, who had it much worse than them all, to get into the VA system and receive the disability help he deserved. Again, Mr. Walt tried to understand why he did not have the serious effects the others were experiencing. What he heard from his colleagues that evening seemed to make it clear. All of the others were experiencing regret and shame for one major reason—it was not that they saw death, saw their friends injured and killed, or that they themselves had suffered lifelong injuries—it was that they had killed and could not forget that another human had died at their hand.

Mr. Walt believes that he did not get PTSD; rather, he feels he was just lucky because he never actually saw the deadly effects of his own actions in battle. Even the time he threw the grenade in May 1968, he did not see that the man he threw the grenade at had in fact been killed. There was no direct visual evidence that he had done so. And neither did he witness an enemy combatant fall and die from his firing at them from the Loach. He is pretty convinced that it must have happened. He clearly shot at enough people that it probably happened. He just did not observe that he killed someone. He said, “I’m just lucky to not have seen that.” After all his war experiences, having seen the gore and waste of war, and still holding personal anti-war views, Mr. Walt sincerely believes that not having the best possible military is the stupidest thing a country or society could do. He believes that there will always be enemies in the world. History has repeated that reality far too many times to fantasize it won’t happen again. He believes there should be a national service requirement for everybody. He believes that serving in the military should come with the full understanding that war is always brutal and can forever negatively affect you. It is the price one sometimes pays for serving. Mr. Walt is proud of his service and military accomplishments. He believes that those tasked with potentially giving their all for their country should be granted all of our best wishes and gratitude for serving. Our country needs, and will always need, our best efforts to counter ever-recurring threats of unchecked corruption and power. And to those who now walk up to him in public and want to shake his hand and thank him for his service, he has learned to say with honest conviction, “You were worth it.” .