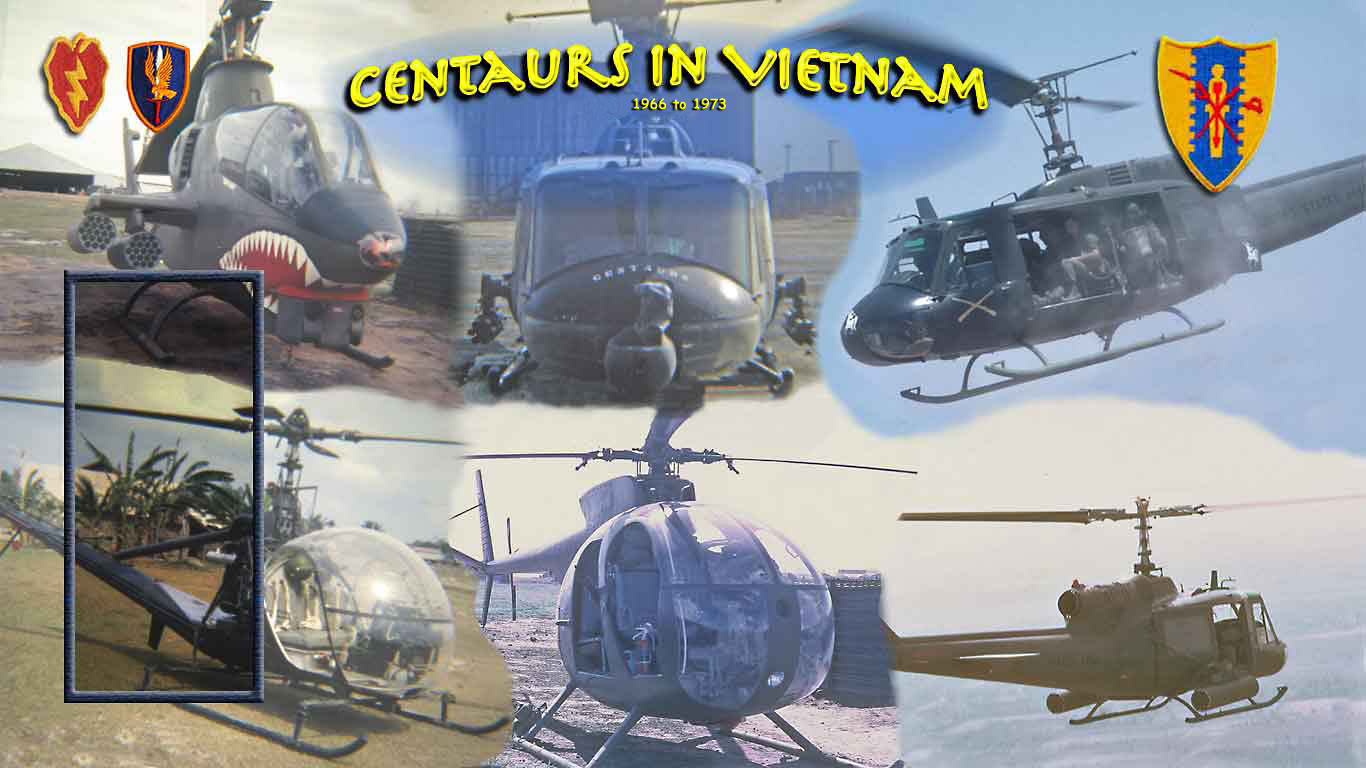

Return to Vietnam, 48 Years Later

Artillery Forward Observer 1966-67

Bain (“Short Round,” field-artillery observer with the Centaurs in 1966-67) and Karen joined a group of 20 tourists led by a Yale professor on a visit to Cambodia and Vietnam in November 2015. The 20-day trip included a week cruising down the Mekong River through Cambodia to Vietnam’s Delta region and stays in Ho Chi Minh City (Saigon) and Hanoi, where we traveled on Air Vietnam. Our group occupied all 12 passenger cabins on a new river ship. The itinerary covered cultural and historical sites, landscapes, opportunities to meet people, traditional dance and theatrical performances, cooking lessons, fine meals of local cuisine, and war memorials in Saigon, Cu Chi, and Hanoi. Bain was the only veteran in the group.

We started in Cambodia by exploring the vast, jungle-covered ruins of Hindu-Buddhist temples at Angkor. Along the Mekong, we stopped at Phnom Penh to see the National Palace, Silver Pagoda, and – grimly -- “killing fields” where the Khmer Rouge massacred and buried some two million of their countrymen in the 1970s. The bloodshed and tyranny were so brutal that the reunified Socialist Republic of Vietnam invaded in 1979 and removed the Khmer Rouge from power. On a river we saw one of many floating villages of Vietnamese living illegally in Cambodia, many of them families of army veterans who stayed behind when their forces withdrew.

Entering Vietnam, we rode sampans to villages where we interacted with local families and observed their farming and artisan work, such as weaving the traditional colored, checked scarves that had been worn by Khmer Rouge and Viet Cong fighters. We also saw Can Tho and My Tho in the Mekong Delta, strategic cities during the “American War,” and visited a floating market. Tied up at a quayside on the river we saw long lines of aging, gray patrol boats left over from the U.S. Navy’s Riverine Force in the war. Our guide told us that Vietnam hoped to buy new patrol craft to challenge China’s occupation of disputed islands in the South China Sea; during our trip the U.S. Government announced that it would partially lift an arms embargo to allow Vietnam to procure the new boats.

Disembarking in Saigon, we plunged into a city of 10 million people – about 10 times as many as during the war – 6 million motor scooters, and 500,000 cars and trucks. Traffic on city streets was daunting: at every stoplight, people on scooters were lined up 12 abreast and 30-40 deep. Modern skyscrapers dwarfed older buildings like the old U.S. Embassy compound (almost seized by Viet Cong in the Tet Offensive of 1968) and the former CIA offices (site of the famous photo of a Huey helicopter landing on the roof during the final evacuation in 1975). The country had come a long way since the war: population had almost tripled to more than 90 million, and the economy – thanks to free-market reforms since 1986 – had attracted foreign investment in industries from clothing to computers and was growing rapidly. We checked into a five-star hotel. Later, in the new U.S. Consulate office tower, Foreign Service personnel briefed our group on economic and political developments. We were told that “an overwhelming majority” of Vietnamese now view the U.S. favorably.

A must-see site was the Presidential Palace, built from 1962 to 1966 at the request of President Diem after the former palace burned down. Uncle Sam paid $5 million for it, and no expense was spared on the interior decoration. Diem never enjoyed the palace, because he was assassinated in 1963, not long before President JFK’s death.

We saw the red room where President LBJ and Robert McNamara were received. LBJ sat in front of a pair of elephant tusks set in dragons’ mouths. We saw other beautifully decorated official rooms and President Van Thieu’s austere bedroom. Then we went to the basement bunker that held living quarters, a map room, a radio room, and a command center, all furnished with standard U.S. desks, chairs, filing cabinets, and communications gear of the era. The war ended at the palace on April 30, 1975, when two tanks (a Soviet T-54 and a Chinese copy) crashed through the front gate. Both types of tank were displayed on the palace grounds.

The War Remnants Museum proved to be another worthwhile stop. In front were U.S. warplanes, helicopters, armored vehicles, and artillery guns captured from the South Vietnamese Army (ARVN) after U.S. troops left. The aircraft still had U.S. insignia and tail numbers. Inside we saw a large exhibit of war photos taken by journalists from around the world and photos of Agent Orange victims, including many with crippling birth defects.

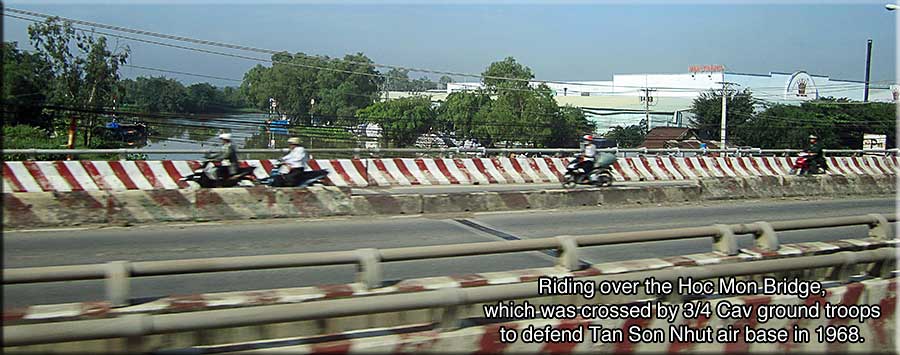

From downtown we took a two-hour bus drive north to Cu Chi, past Tan Son Nhut Airport, formerly an American air base, and over the Hoc Mon bridge, important to the 3rd Squadron, 4th Cavalry in the defense of Tan Son Nhut during Tet in 1968.

From downtown we took a two-hour bus drive north to Cu Chi, past Tan Son Nhut Airport, formerly an American air base, and over the Hoc Mon bridge, important to the 3rd Squadron, 4th Cavalry in the defense of Tan Son Nhut during Tet in 1968.

On the way we saw signs to Trang Bang, home of the “napalm girl” in a famed photo and a checkpoint along the “main supply route” for U.S. forces to the north. We drove right up to the main gate of the former U.S. 25th Infantry Division base, now a Vietnamese military installation off-limits to foreigners. Turning right, we drove through Cu Chi town and north into the Ho Bo Woods (the name means “buffalo swamp with some trees”) – once a devastated battlefield familiar to Centaurs. The landscape around Cu Chi was green with rice and manioc fields with modern farm equipment, rows of rubber trees with cups collecting latex from cuts in the bark, and a privately owned factory processing rubber for export to China.

Soon we arrived at a tunnel area that is open to tourists, across the “mushroom” curve of the Saigon River from Ben Suc village, scenes of many Centaur combat actions. The entire tunnel complex covers some 30 square miles, bordering the river’s right (west) bank and extending under Cu Chi base. The first tunnels were dug during the French War. There are three levels of tunnels in the “Never-Ending System,” one at 12-14 feet deep, one at 18-25 feet, and one at 33-40 feet. Some of the tunnels connect to the river. Excavation of the rock-hard laterite clay was a prodigious feat of engineering and hand labor. Bunkers as large as 5 meters by 10 meters, supported by wooden beams, were close to the surface and used as clinics, kitchens, mess halls, conference rooms, etc. Ventilation tubes ran from lower levels to the surface; the outlet of one was disguised in a man-made termite mound.

We were met and briefed by Mr. Num, a guerrilla veteran. Born in 1950 and raised in Cu Chi, at age 10 he carried supplies to the Viet Cong and at age 17 became a guerrilla, living in the tunnels and leading small-unit (three men) ambushes at night. On 1 November 1967, three days after Bain’s departure from Vietnam, Num saw 25th Infantry Division tanks coming toward his tunnels. He shot a rifle and then a rocket-propelled grenade at the tank, which failed to stop it. The tank crew fired a machinegun at his position, taking out his right eye and right arm. He was treated in a tunnel first-aid bunker for a month, as it was too dangerous to transfer him to a tunnel hospital. After recovering from his wounds, he did paperwork until 1975, learned to shoot a rifle with one arm, and worked 12 more years in the Cu Chi military district before retiring. He claimed to have no interest in communist ideology and said he was just fighting for independence.

We were met and briefed by Mr. Num, a guerrilla veteran. Born in 1950 and raised in Cu Chi, at age 10 he carried supplies to the Viet Cong and at age 17 became a guerrilla, living in the tunnels and leading small-unit (three men) ambushes at night. On 1 November 1967, three days after Bain’s departure from Vietnam, Num saw 25th Infantry Division tanks coming toward his tunnels. He shot a rifle and then a rocket-propelled grenade at the tank, which failed to stop it. The tank crew fired a machinegun at his position, taking out his right eye and right arm. He was treated in a tunnel first-aid bunker for a month, as it was too dangerous to transfer him to a tunnel hospital. After recovering from his wounds, he did paperwork until 1975, learned to shoot a rifle with one arm, and worked 12 more years in the Cu Chi military district before retiring. He claimed to have no interest in communist ideology and said he was just fighting for independence.

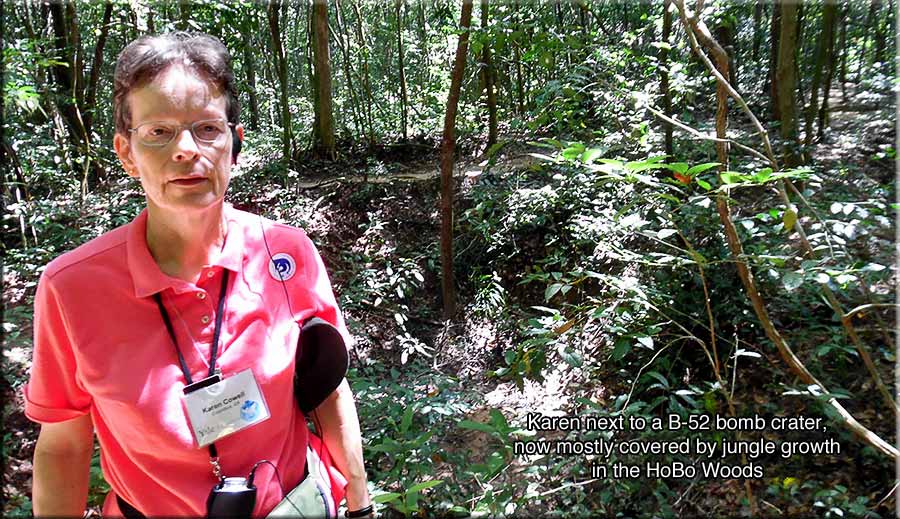

After the briefing, we tromped through the woods, which are all secondary growth, since the foliage in this area was destroyed during the war. Bamboo thickets and jungle trees had reclaimed much of the ground and provided shade along the paths. We passed many B-52 bomb craters, now partially filled with vegetation. They looked smaller than the “swimming pools” that Centaurs saw from the air long ago.

We were given the opportunity to descend into three original tunnels. They are very low and narrow (about one meter high, and less than half a meter wide). They are lit by electricity now for the convenience of the tourists, but had no lighting during the war. Bain saw bats. It was unnerving to walk through stooped over, unable to see anything, and we felt claustrophobic after only a few minutes. We were glad to get out. It is difficult to imagine that many people lived for years down there. A park guide showed us some well- camouflaged tunnel entrances and exits (“spider holes” to the Centaurs). American “tunnel rats” (including some Centaur Aero-Riflemen) were tasked with searching the tunnels. Teenage Vietnamese girls known as “tunnel finders” guided the guerrillas to the entrances. During our visit we also saw a display of booby traps that were used inside and outside of the tunnels. Many featured sharp stakes – “punji stakes” – hidden in holes or under foliage that were designed to pierce the feet, legs, or torso of a victim. Also on display were caches of unexploded U.S. bombs and shells, antitank weapons, and aircraft rocket pods.

On the way back through Cu Chi town, we stopped at a cemetery for 12,000 Vietnamese soldiers -- mostly local Viet Cong and a few North Vietnamese. The cemetery was beautifully laid out with rows of grave markers showing the name, place of origin, and date of death of each fighter except – on 10% of the graves – the notation “Lost Soldier.” In the center was a monument and statue of a mother (the nation) holding her dead son. Of some 20,000 guerrillas around Cu Chi, only 3,000 were not killed or wounded. Bain was very moved. In all, it was an emotionally draining day

Mr. Nam, our local guide in southern Vietnam, told us about his family’s involvement in the war: Nam’s family came from Haiphong, a deep-water port 120 kilometers east of Hanoi. His mother’s younger brother was killed in 1975, shortly before the end of the war, by a South Vietnamese air strike while fighting in the Ho Bo Woods. Another uncle manned anti-aircraft artillery in Hanoi. Nam’s family moved south in 1976 to look for the uncle who had disappeared in the Ho Bo. After 31 years (in 2006) someone found his bones in a bone jar, along with a used penicillin vial that had a paper inside with the soldier’s name and address. This was a common means of identification, as the North Vietnamese did not have dog tags. Another uncle is still unaccounted for, one of 500,000 Vietnamese missing in action on both sides.

Mr. Nam, our local guide in southern Vietnam, told us about his family’s involvement in the war: Nam’s family came from Haiphong, a deep-water port 120 kilometers east of Hanoi. His mother’s younger brother was killed in 1975, shortly before the end of the war, by a South Vietnamese air strike while fighting in the Ho Bo Woods. Another uncle manned anti-aircraft artillery in Hanoi. Nam’s family moved south in 1976 to look for the uncle who had disappeared in the Ho Bo. After 31 years (in 2006) someone found his bones in a bone jar, along with a used penicillin vial that had a paper inside with the soldier’s name and address. This was a common means of identification, as the North Vietnamese did not have dog tags. Another uncle is still unaccounted for, one of 500,000 Vietnamese missing in action on both sides.

On a trip extension, we flew out of Tan Son Nhut to Hanoi. On the bus ride into the city, our local guide Mr. Tri told us that the Vietnamese feel threatened by China, which is only 220 kilometers north of Hanoi. China has dams on the Red River, which flows through Hanoi. The dams wreak havoc in Vietnam, as the Chinese release large volumes of water that flood the downstream Vietnamese farms. The Vietnamese joke ruefully that China wouldn’t have to attack Vietnam with weapons – they’d only need to have a billion Chinese simultaneously pee in the Red River!

We checked into the Sofitel Legend Metropole Hotel, a lap of luxury built under French rule in 1901. This part of Hanoi is westernized and prosperous; the capital city now has 8 million inhabitants. Bac (Uncle) Ho might be appalled by the capitalist consumerism here: there’s even a stock exchange. In the early evening we walked around and saw the beautiful old French-style Opera House and the new Hanoi Opera Hilton. Tri said that cab drivers often confuse the real Hanoi Hilton with the former prison.

At the Metropole, we toured the basement bunkers that were constructed in 1966-67. They comprised four small rooms, each capable of holding 10 guests (not staff!) in the event of B-52 bombings. Joan Baez used the bomb shelter during the 1972 Christmas bombing. After the war, the rooms were forgotten but were rediscovered in 2012 during construction of the hotel’s Bamboo Bar.

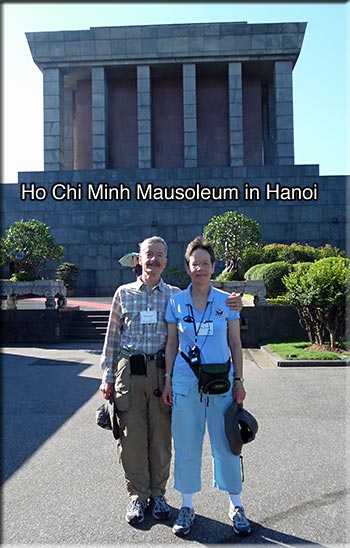

We paid an early morning visit to Ho Chi Minh’s mausoleum near the former presidential palace. Uncle Ho didn’t want to live in the palace and chose a much smaller building on the grounds to be his home and office. Later on, he had a stilt house made of teak nearby – on stilts because he admired the architectural style of the south, where such houses are built on river flood-plains.

Ho wanted to be cremated and his ashes spread all over the country, but his successors thought it would be better to have him embalmed so new generations could see him. We were the first visitors of the day, and it looked as though the embalmers did a good job on him (no photos allowed – too bad). The mausoleum is a huge building with an elite guard whose family politics have been vetted for at least three, even four generations. Uncle Ho is the George Washington of Vietnam and is held in very high esteem. By the time we left the mausoleum, hundreds of Vietnamese were waiting in line to view the body, and many more were touring Ho’s houses and the palace grounds.

After visiting Uncle Ho, we went to the infamous POW prison known as the “Hanoi Hilton.” Originally called Hoa Lo, the building was constructed in 1896 as a ceramics kiln. Later, the French converted it to a prison called Maison Centrale and used it to house and torture Vietnamese revolutionaries from 1930-54.

Most of the exhibits describe barbarous treatment of the Vietnamese by the French; only a relatively small area describes the incarceration of Americans, principally flyers, from 1965-73. The photos of Americans show them enjoying basketball, chess, and volleyball and celebrating Christmas. It looks rather like a resort! John McCain’s flight suit is in a glass case, but the cell he had occupied was destroyed to make way for an office building (or so they said). All of the written documentation in the prison notes that the Vietnamese treated the “criminal” Americans humanely while they were in “temporary detention.” (Some were detained “temporarily” for 8 years.) Karen has read books about Hoa Lo, and no one else describes the period of American incarceration as being anything other than brutal, with spoiled food, little medical care, nonexistent hygiene, and days on end of interrogation and torture. Well, history is written by the victors

At the end of our Hanoi tour, we took advantage of a late airport departure to visit the Women's Museum. It is a splendid facility with first-rate exhibits about traditional clothing, heroic women (all of whom happened to be 20th-century revolutionary soldiers or guerrillas), the cult of the goddess, and everyday life of women in rural Vietnam. We learned that the deputy commander of the guerrilla forces at Cu Chi while Bain was there was a girl of 18, named Vo Thi Mo, and that 40% of the guerrillas were women. Who says women aren't capable of combat?

We also saw the Military History Museum, which is mostly about the Vietnamese struggles against France, Japan, and the U.S. in the 20th century. It tells a compelling story of their determination and ingenuity, documented with photos, terrain models, and dioramas. A diorama shows heavily loaded logistics bicycles being walked through the jungle on the Ho Chi Minh Trail: one carries a 75-mm. recoilless rifle and bags of supplies, and another is loaded with huge sacks weighing (so they claim) up to 600 kilograms – nearly the limit for a U.S. ¾-ton truck! Outdoors we explored a park full of Soviet and captured American hardware, including armored vehicles, artillery pieces, helicopters, and fighter planes -- including a MiG-21 with which 12 pilots destroyed 14 U.S. aircraft from 1967-69.

Mr. Tri, our guide in Hanoi, was born in Hue (central Vietnam). His father fought for the South Vietnamese Army and spent four years in a re-education camp after the war to correct his “wrong thinking.” He had been a history teacher, but was unable to get work as a teacher again because of his association with the wrong side. Two of Tri’s uncles also served in the South Vietnamese military. Another uncle manned an anti-aircraft gun in Hanoi, shot down several American planes, and rose to the rank of colonel. Probably many families had divided loyalties in the war; only years later was Tri’s family reunited in Hue.

There’s plenty of sad 20th-century history in Cambodia and Vietnam, but there’s lots that’s inspiring and uplifting, too. Most of the population was born after the war, and to them it’s ancient history and of little concern. They just want to live their lives in peace and prosperity, like the rest of the world. This was a great trip, a real eye-opener for us. It was wonderful to see the people of two ravaged countries doing pretty well after so many years of violent conflict.

.