Following my service with F-Troop, 4th Calvary (Centaurs) from August 1971 until April 1972, I returned home, attended graduate school at Clemson University and became a Wildlife Biologist. Little did I ever dream that my chosen profession would ever lead me back to Vietnam, but it did and it provided one of the most memorable experiences of my life.

Following my service with F-Troop, 4th Calvary (Centaurs) from August 1971 until April 1972, I returned home, attended graduate school at Clemson University and became a Wildlife Biologist. Little did I ever dream that my chosen profession would ever lead me back to Vietnam, but it did and it provided one of the most memorable experiences of my life.

The way this happened involved 35 years in the Wildlife Profession, but I will not bore you with all those details. Suffice it to say that after 28 years working with a state game and fish agency I retired and went to work with the U.S. Department of Agriculture working as a Wildlife Disease Biologist. In 2008, I was one of 43 biologists nationwide responsible for routine sampling of wildlife for diseases that might impact agriculture or human health and was on-call to respond within 48 hours to emergency wildlife disease threats anywhere in the US. The job is challenging and often exciting. In my 35 years in the profession, it is the best job I’ve ever had. With that bit of background, below is the account of my “Second Tour of Duty”

My cell phone rang on my way home from work on a Monday afternoon in August 2008. It was Dr. Dale Nolte, Assistant Wildlife Disease Coordinator for International Affairs, wanting to know if I was available for international travel. I knew I was just completing the final phase of a swine monitoring project, I had a few days of unplanned work in the office, so I said: “yes, when and where?” Dale said: “Sunday, Vietnam.” I had less than a week to pack, get tickets, get necessary malaria medications, and put together some equipment to demonstrate trapping wild birds for disease monitoring. Fortunately, I had some experience with similar trips to China and Chile and knew a little of what to expect.

Vietnam is one of the world’s hot spots for the high pathogenic Asian strain of avian influenza. Their commercial poultry flocks have been plagued with the virus and the first human cases were detected as early as 2004. The Vietnam government has been very active in their attempts to control the disease in commercial poultry and backyard flocks of chickens and ducks. Little is really understood about the disease in wild birds, however, and that is why their government asked for our help.

Not all international travel involves such short notice as this one, but communication is always a challenge. It seems that Dr. Nguyen van Long with the Vietnamese Department of Animal Health wanted us to come over and conduct some training involving monitoring wild birds around the first of October. Dale responded that it would be better to do it before the end of the fiscal year. Dale was thinking of having it the last couple of weeks in September. A few days passed and Dr. Long responded that he had rescheduled the training and was set up and ready to go for the last week in August and the first week in September. This left Dale with a week to plan and get trainers over. That is when he called Mike Marlow, disease biologist from Oklahoma, and me. Both of us had helped with similar training in China and we were both available on short notice.

For me this was going to be a trip involving a lot of mixed feelings and emotion. You see, this is the second time my government has sent me to Vietnam. The first trip was 37 years prior as a young enlisted solider with an air-cavalry unit. I was an avionics specialist on a small Army air base near the village of Lai Kke about 40 km north of Saigon. Going back to Saigon, now Ho Chi Minh City, was something I never expected to do.

For me this was going to be a trip involving a lot of mixed feelings and emotion. You see, this is the second time my government has sent me to Vietnam. The first trip was 37 years prior as a young enlisted solider with an air-cavalry unit. I was an avionics specialist on a small Army air base near the village of Lai Kke about 40 km north of Saigon. Going back to Saigon, now Ho Chi Minh City, was something I never expected to do.

The first leg of our trip was to include one night in Saigon and then a road trip to Dong Thap, about a 3 hours drive west of Saigon on the Mekong Delta. Here we would do classroom training and then field work on a large wildlife sanctuary. Oddly enough we flew into Tan Son Nhut International Airport. This was the very same airport from which I arrived and left in 1971 and 72. The old military revetments used to house F-4’s and other fighter aircraft could still be seen along the runway. Nothing else was the same, however. Our long, low glide path took us over 4-lane highways and modern interchanges and new construction that showed just how much the country had changed. I mention the long low glide path, because my first approach to Tan Son Nhut was under a red alert with a steep emergency decent and a fighter on each wing.

As we touch down at Tan Son Nhut, the Vietnam nationals let up a cheer. Not unusual for citizens returning to their native land, but it sent chills up my back. I instantly remembered the cheer of the GI’s when our wheels left Vietnam on that clear night in April, 1972. I remembered looking out the window as we were not more than 1000 feet in the air and seeing the enemy’s white tracers from a fire fight just off the end of the runway. I knew this trip was going to be different from my other international travels, but until that moment, I didn’t realize how different.

We arrived at our hotel shortly after midnight and had a message to meet Dr. Long in the Lobby about 5:30 am. It was a short time to rest after a 16 hour, 20 minute trip including a 2 hour layover in Hong Kong. With jet lag and adrenalin I was wide awake and ready to go anyway. The drive to Dong Thap was an experience. The roads along the way were packed with a solid stream of motorbikes and bicycles driving handlebar to handlebar the entire width of the road. Gone were the three-wheel French Lambrettas and an occasional Vespa that I remembered. Japanese built motorbikes are now the standard. While conical straw hats called Nón lá are still common, the dress was much more western. The casual dress for women 37 years ago was black silk pants and a cotton print shirt. You have to look hard to find anyone in black silk pants any longer. Since a helmet law was passed about 6 months prior, Nón lá may soon be a thing of the past also.

On our drive to Dong Thap I was still unsure how to handle discussions about my previous visit. Dr. Long, during our first meeting, asked me in routine conversation if I had ever visited Vietnam before. I confided that I had, but it was in the early 70’s. He immediately understood that I had come over as a soldier. That was not the case with a twenty-something veterinarian who rode with us to Dong Thap. She too, in making conversation, asked if I had ever visited her country before. I said: “Yes, thirty-seven years ago”. She responded: “My, that was a long time ago. I believe that was before we gained our freedom in 1975. Were you visiting Hanoi or Saigon?” I was a bit taken aback. John McCain was “visiting Hanoi” at the time but not me. I realized that she had no idea why I had been over there in 1971. I somewhat reluctantly told her that I was a soldier stationed near the village of Lai Khe a little north of Saigon. Obviously embarrassed, she admitted that she did not know her history very well. When you think about it, however, it is not that surprising. Ask almost any twenty something in the US about events 40 years ago, and I suspect you would get the same lack of awareness. I just expected the whole war experience to still be on the minds of the Vietnamese. Clearly it was not. In fact during our drive I started looking for people that would have been alive when I was there last. I doubt, of the thousands of people we passed, a half dozen were old enough to have been alive during the war.

We arrived in Dong Thap about mid-morning and proceeded directly to our classroom. Only then did we see an agenda for the training. While we expected to be doing field training and had equipment, supplies and dress to do it, the training Dr. Long had set up was two and a half days of classroom, a day in the field and a final half day for wrap-up and presentations. A similar training session was also scheduled near Hanoi the following week. That is the difficulty with international work where a language barrier is always present. Flexibility is the key. Try as you might to gain understanding via e-mail of what your host is expecting, you never know until your arrival what is exactly expected. Following introductions all round, Dr. Long indicated that he would be lecturing that morning on the avian influenza in Vietnam and suggested we go to our hotel, check-in and have some rest until mid afternoon. We went to the hotel and immediately started working on classroom presentations. Of course the first rule in public speaking is to know your audience. We had expected to be training wild bird trappers in the field. From our introductions we were dealing with laboratory people, and what would be equivalent to our veterinary medical officers and animal health technicians in the US. Unfortunately, few other countries have the equivalent of a “wildlife biologist/manager” professional. Making the challenge even more difficult was that Dr. Nolte, Mike Marlow, nor I are experts in Southeast Asian wildlife. We decided our best approach would be to provide our expertise on trapping equipment, sampling techniques, record keeping, and personal safety and suggest that they rely on local people who knew the habitats and the animals for advice on actual capture. Our suggestion to the audience that they rely on local people for trapping experience seemed to be somewhat of a surprise to them. We knew, however, that there was an active, but apparently illegal wild bird trade that had been going on for hundreds, if not thousands of years. This experience of bringing live wild birds to market was exactly the type of experience they would need in sampling wild birds for avian influenza. No experience Mike, Dale or I have in trapping birds in North American habitats could approach that of those local people who had being working with those species and habitats for generations. All that was needed was guidance on humane handling, some personal safety guidelines and then allow the local people to use the equipment we were demonstrating guided by their invaluable knowledge of the local birds and their habitats.

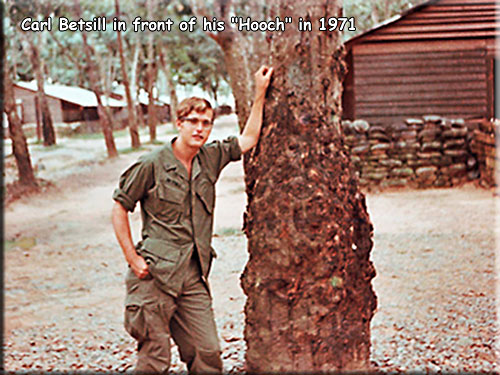

My first presentation was to begin on Wednesday morning. I had brought a cannon net and a couple of mist nets. Mike had brought a variety of other traps used to catch small song birds and raptors. My presentation involved explaining the operation of each type of capture device and what type of birds could be captured with them. Dale had provided a PowerPoint presentation previously translated into Vietnamese that helped explain the equipment. I had added a few pictures from the files that I brought with me. I also added a picture of me at Lai Khe from 37 years ago. Dale was a bit apprehensive and warned me that many in the audience were from the north and might take offense to reminders of the war. I assured him that I would be careful. I knew many were already aware I had been there during the war because of my conversations with the few that spoke English. I decided the best approach was to confront the situation head on. My first slide was a picture taken in 1971 outside my “hooch”. I related that many had asked me if I had ever visited their country before. I told them that I reluctantly had to admit that I had been there as a solider thirty-seven years previously and I was honored their government had invited me back to work with them on a serious livestock issue that was important to both our nations. From the smiles on their faces and the nods of approval, I knew I had taken the right approach. Though it was strange for me to stand on a stage with a bust of “Uncle Ho” looking over my shoulder, I knew I could now hold my head up and be proud of both my trips to their country.

My first presentation was to begin on Wednesday morning. I had brought a cannon net and a couple of mist nets. Mike had brought a variety of other traps used to catch small song birds and raptors. My presentation involved explaining the operation of each type of capture device and what type of birds could be captured with them. Dale had provided a PowerPoint presentation previously translated into Vietnamese that helped explain the equipment. I had added a few pictures from the files that I brought with me. I also added a picture of me at Lai Khe from 37 years ago. Dale was a bit apprehensive and warned me that many in the audience were from the north and might take offense to reminders of the war. I assured him that I would be careful. I knew many were already aware I had been there during the war because of my conversations with the few that spoke English. I decided the best approach was to confront the situation head on. My first slide was a picture taken in 1971 outside my “hooch”. I related that many had asked me if I had ever visited their country before. I told them that I reluctantly had to admit that I had been there as a solider thirty-seven years previously and I was honored their government had invited me back to work with them on a serious livestock issue that was important to both our nations. From the smiles on their faces and the nods of approval, I knew I had taken the right approach. Though it was strange for me to stand on a stage with a bust of “Uncle Ho” looking over my shoulder, I knew I could now hold my head up and be proud of both my trips to their country.

We finished out the week with a trip to Tram Chim National Park and a further discussion on how to employ local trappers to assist in collections. I left convinced that they had expected the “American experts” to relate to them some magical formula that they could use to sample wild birds. What we did tell them is that it was a difficult and possibly expensive endeavor, but through combining local knowledge of bird habitats and behavior with modern capture equipment it would be possible to establish an effective wild bird disease monitoring program. With the help of the US and the United Nations many Southeast Asian countries have already established effective programs. We are hopeful Vietnam will follow suit.

Our trip to Dong Thap ended Saturday about noon and we returned to Ho Chi Minh City. Our plans were to depart for Hanoi on Monday and present a similar program to Department of Animal Health personnel in that part of the country. This meant we had Sunday off and I knew exactly how I wanted to spend it. On Sunday morning I approached an English speaking bell hop and asked if he could help locate a taxi driver who spoke English. After quizzing a few in front of the hotel, he introduced me to a driver whose English was passable.

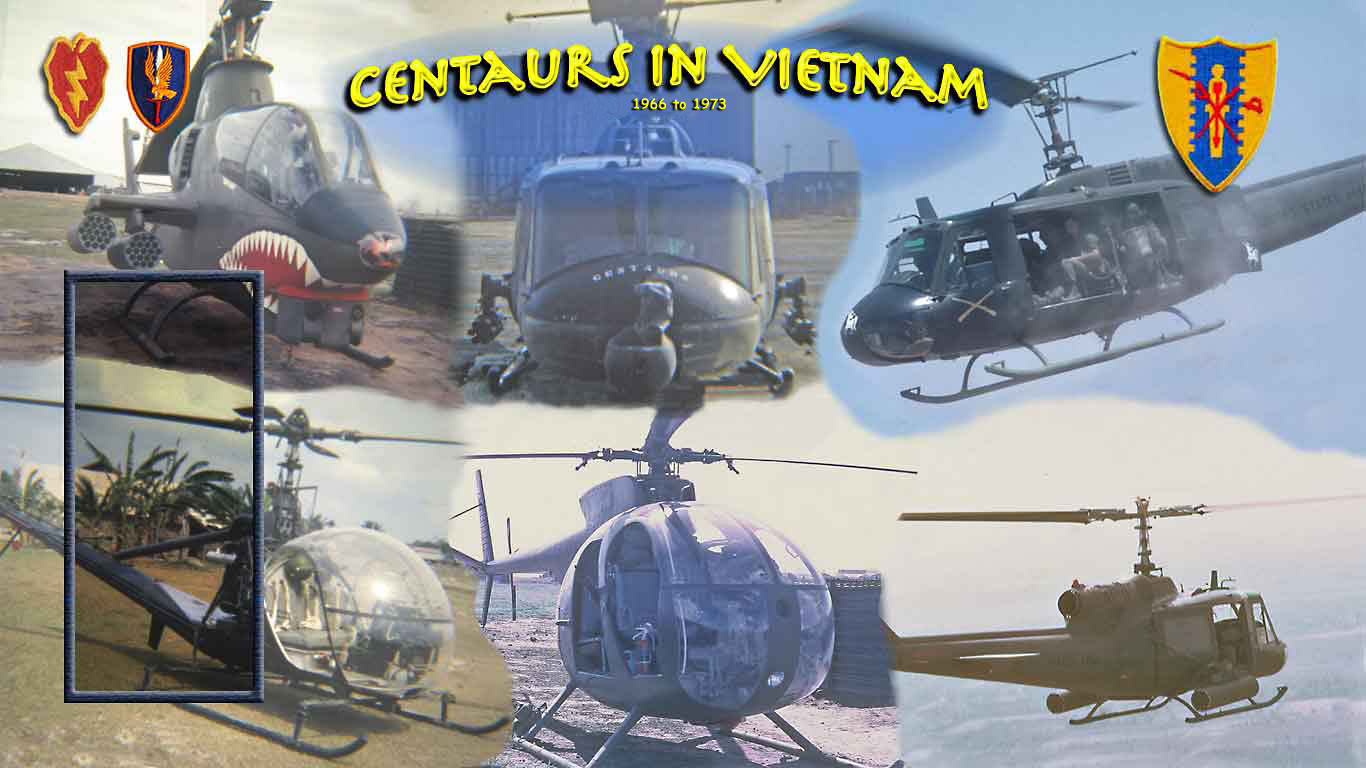

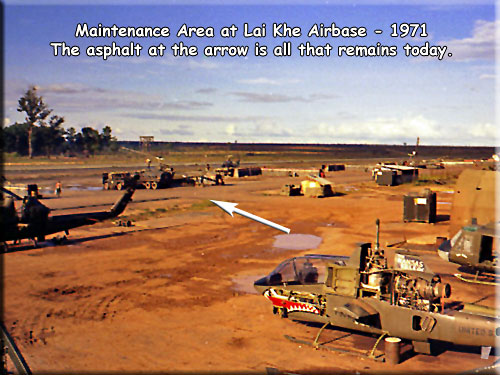

The base where I was stationed at in 1971 was only about 40 kilometers north near the village of Lai Khe. It was an important base during the war and was located near what was known as the “Iron Triangle” along an infamous stretch of highway known as “Thunder Road”. When I was there it was home for F-Troup, 4th Air Cavalry which flew hunter-killer teams consisting of cobra gun ships and small observation helicopters. To my surprise, neither the driver nor bell hop had ever heard of Lai Khe. I told the driver, “no problem, just take me to Ben Cat”. Ben Cat was the district seat of government for the region and was only about 3 km south of Lai Khe. He knew the town, so we headed out. A trip that would have taken 20 minutes back home, took about an hour and a half weaving through a steady stream of motor bikes. Upon our arrival in Ben Cat the driver seemed confused. I told him to take QL-13 north, but apparently he either could not understand me or figured I didn’t know what I was talking about. Finally he stopped and asked a local. Two guys jumped on a motor bike and led us to Lai Khe. Thunder Road when I last saw it was a one-lane black top road; we were now on a 4-lane highway. I knew then that finding the old base would be a challenge. As we got near, however, I began to see rubber plantations. Our old base was built in the middle of an old Michelin rubber plantation. We stopped again and the driver asked if anyone knew where the American army base was. One of the locals spoke up and said that during the “American war” there were many Americans stationed at what was now a Rubber Research Institute” just ahead on the left. When we got there I recognized it as the old Military Assistance Command –Vietnam (MACV) local headquarters. It was not part of our base but just south and on the opposite side of the road. Fortunately, I had my computer and an old aerial photograph I had taken flying into the base. I showed the picture to the driver and we were able to orient ourselves by locating the gate of MACV and the present-day Rubber Research Institute. Driving another kilometer or so north I got out and walked behind some stores and found an asphalt strip that was once our flight-line. The rubber plantation there during the war had been clear-cut and re-planted to young rubber trees. I was unable to find any structure still standing from the war. I did find an odd area devoid of vegetation surrounded about knee high with our old razor wire. I could only surmise that it was the old ammo dump destroyed by Viet Cong shortly after I left. The razor wire was obviously meant to keep anyone from inadvertently stumbling on to 40 year-old unexploded ordinance.

The base where I was stationed at in 1971 was only about 40 kilometers north near the village of Lai Khe. It was an important base during the war and was located near what was known as the “Iron Triangle” along an infamous stretch of highway known as “Thunder Road”. When I was there it was home for F-Troup, 4th Air Cavalry which flew hunter-killer teams consisting of cobra gun ships and small observation helicopters. To my surprise, neither the driver nor bell hop had ever heard of Lai Khe. I told the driver, “no problem, just take me to Ben Cat”. Ben Cat was the district seat of government for the region and was only about 3 km south of Lai Khe. He knew the town, so we headed out. A trip that would have taken 20 minutes back home, took about an hour and a half weaving through a steady stream of motor bikes. Upon our arrival in Ben Cat the driver seemed confused. I told him to take QL-13 north, but apparently he either could not understand me or figured I didn’t know what I was talking about. Finally he stopped and asked a local. Two guys jumped on a motor bike and led us to Lai Khe. Thunder Road when I last saw it was a one-lane black top road; we were now on a 4-lane highway. I knew then that finding the old base would be a challenge. As we got near, however, I began to see rubber plantations. Our old base was built in the middle of an old Michelin rubber plantation. We stopped again and the driver asked if anyone knew where the American army base was. One of the locals spoke up and said that during the “American war” there were many Americans stationed at what was now a Rubber Research Institute” just ahead on the left. When we got there I recognized it as the old Military Assistance Command –Vietnam (MACV) local headquarters. It was not part of our base but just south and on the opposite side of the road. Fortunately, I had my computer and an old aerial photograph I had taken flying into the base. I showed the picture to the driver and we were able to orient ourselves by locating the gate of MACV and the present-day Rubber Research Institute. Driving another kilometer or so north I got out and walked behind some stores and found an asphalt strip that was once our flight-line. The rubber plantation there during the war had been clear-cut and re-planted to young rubber trees. I was unable to find any structure still standing from the war. I did find an odd area devoid of vegetation surrounded about knee high with our old razor wire. I could only surmise that it was the old ammo dump destroyed by Viet Cong shortly after I left. The razor wire was obviously meant to keep anyone from inadvertently stumbling on to 40 year-old unexploded ordinance.

It was an odd feeling being back. It was obvious that there had been no attempt to preserve anything that reminded them of the war. What was an important and memorable place in my life was now just a small insignificant village paved over by a 4-lane highway. In 1971 everyone in the Saigon area knew of Lai Khe, now, no one living more than 5 km away seemed to have ever heard of the place. I suppose that is a good thing. At least time heals the scars war leaves on the land, though often not the scars in the hearts of those who fought.

Monday morning we boarded a flight to Hanoi. I pictured Hanoi as a dull, backward, industrialized city. I was surprised to find a bright, cheery city with lakes and city parks scattered throughout and shops crowded with international tourist. More modern than Ho Chi Minh City, but streets full of handle bar to handle bar motorbikes gave the two cities something in common. We quickly learned that to cross a street, you simply start walking and allow the traffic to flow around you. What ever you do, don’t lose your courage and stop or hesitate. This will throw the drivers timing off and cause an accident! Monday evening we had supper on a porch overlooking a five way intersection with no traffic signals or stop signs. We were entertained the whole evening watching in amazement, the perfect blending of five steams of motorbikes, pedestrians and occasional automobile without any discernable traffic rules.

Tuesday morning early Dr. Long met us and we proceeded to our meeting site and hotel bordering Haiphong harbor. We repeated a similar program there for the next 4 days. Despite my misgivings about how we would be received in a city our country bombed for years and on a harbor we mined extensively, we were made to feel welcome just as we were in the south. In fact, one of the participants, Dr.Tuc was my age and had served during the war in the defense of Hanoi. We became good friends and had a toast to “old soldiers” during a supper get together one evening.

Tuesday morning early Dr. Long met us and we proceeded to our meeting site and hotel bordering Haiphong harbor. We repeated a similar program there for the next 4 days. Despite my misgivings about how we would be received in a city our country bombed for years and on a harbor we mined extensively, we were made to feel welcome just as we were in the south. In fact, one of the participants, Dr.Tuc was my age and had served during the war in the defense of Hanoi. We became good friends and had a toast to “old soldiers” during a supper get together one evening.

We had been somewhat disappointed we had not been able to spend more time in the field during our classes at Dong Thap, but here we were able to set out mist nets right outside the class room. We captured only one species, a very small kingfisher. We used these birds, as well as other species obtained from a local bird market, to demonstrate disease sampling techniques. While there is actually little chance of humans contracting avian influenza from wild birds, those of us directly handling the birds took proper precautions with gloves, eye protection and masks. Those participants dressed in white suits were practicing wearing the full protection they would be required to wear in the event of a known die-off of poultry or wild birds. We are fortunate that this particular influenza virus has never been detected in North America.

Our final day of training consisted of a tour of a wildlife sanctuary directly across from a large container ship facility. Our trip there passed through fishing villages where reed boats were being made as they have been for hundreds of years and fish baskets were being woven from cane. The picture illustrates this mixture of old and new. In the foreground are two ladies in their Nón lá poling a reed boat, while in the background is a large modern container ship ready for unloading its international cargo at Haiphong harbor. Our training also was about the old and new. We were bringing new techniques and equipment for monitoring a new and menacing disease threat. We were asking them, however, to rely on the experience of people like those pictured in this photo to help in sampling the wildlife populations in question.

We feel our trip was worthwhile. The Vietnamese government is genuinely interested in starting a wild bird monitoring program. We created some good will between our governments by addressing some serious problems that could affect both our citizens. Right now, avian influenza or “bird flu” is a disease of poultry and, although it has infected a small number of humans, the most immediate threat is to the poultry industry. By better understanding how this virus is maintained and spread in wild birds we can better protect the agricultural industry and the economy. There is also a real but not well understood risk that the virus could combine with human or swine viruses and be spread from person to person. The worry is that such a combination of viruses could lead to a new and serious worldwide flu epidemic. The likelihood of this happening is up to much debate. We are fortunate, that after more than a decade of the existence of the Asian strain of this virus, this has not happened. We are also fortunate that after thousands of tests of wild and domestic birds in North and South America, we seemed to still be free of this virus. Only by working with other countries, however, can we begin to understand how this virus is spread and how it is changing. This knowledge will enable us to be prepared in the event the disease needs to be dealt with in our country.

As I boarded the bus at our final training site, Dr. Tuc handed me a self-addressed envelope. Through the translator he asked me to send him a picture I had taken of he and I and to my surprise he also asked that I send him a picture of me when I was a soldier in the south. We embraced a last time and departed friends. Never in my wildest dreams could I have imagined that moment so long ago in such different times...Carl