Loss of the Iron Butterfly - 1969

As told by then WO1 Thomas “Silent Sam” Dooling - see award of Silver Star

see Jack Craig video (not quite as accurate)

On 28 October 1969, the Centaur Loach named the 'Iron Butterfly’ was shot down - the pilot 1LT Mark Jackson was killed by the enemy gun fire, his Observer was wounded in the left elbow and his Crew Chief was seriously injured (broken femur & multiple other injuries) in the crash. Sam Dooling & Jack Craig were flying the cover Cobra when the Loach was shot down. The Cobra crew engaged the enemy gunners, causing them to quit firing, landed the Cobra and rescued the survivors of the crash. The following is the story of that incident as told by Sam Dooling.

For the past 50-odd years, I’ve admired combat veterans that can spin a compelling story of their experiences in Vietnam. I’ve known some who keep their anecdotes of combat experiences light and amusing, but I’ve seen others that become too enmeshed in the gory details to make it enjoyable for the general reader.

Now that I’m a retired empty nester, I’ll see what I can do to make this tale palatable to most without becoming too somber. Keep in mind that this incident happened 50+ years ago, so if some of the story seems a little blurry, blame it on time’s effect on my gray matter. And, as always, remember that the fundamental difference between a fairy tale and a war story comes down to one line. Fairy tales begin with, “Once upon a time;” war stories begin with, “And this ain’t no bullshit.”

Prelude

In August of 1967, President Lyndon B. Johnson sent me a postcard offering to employ me for the next couple of years in his endeavor to halt the communist hordes (i.e., I was drafted). I headed to Fort Lewis, Washington (outside Seattle/Tacoma) in late September for basic training to become an infantryman. For those of you who have never experienced the Seattle/Tacoma weather in late fall/early winter, I can attest to the weather being cold and damp. As with all basic training programs, much of your time is spent out in the elements — so we were all cold and damp pretty much 100% of the time.

As with all inductees, I was given a battery of tests to determine how the Army might best use me. As the test scores came back to the unit, those of us that tested well were given opportunities to participate in other testing to see if we were qualified to go the Officer Candidate School, West Point, Flight Training, etc. Of note, all of this additional testing was conducted indoors in climate-controlled classrooms (i.e., not a cold and damp environment).

It seems that I was blessed with pretty good test taking skills (and an aversion to being cold

and damp), so as I was afforded the opportunity to take additional tests (indoors), I volunteered for any and all tests they wanted me to take. The next series of testing indicated I qualified to go to OCS or Warrant Officer Helicopter Flight training. On to another level of testing to see if I had the spatial awareness for being a pilot (again, indoors), and then a flight physical (do I need to mention it was indoors). Passing all of these tests with flying colors, the Army determined that I could serve as cannon fodder in more than one way, so they offered to teach me how to fly helicopters before sending me off to war. Even at the tender age of 19, I figured out that maybe being a helicopter pilot would be preferable to slogging around in the mud carrying a M- 16 and a 75 lb. ruck sack on my back.

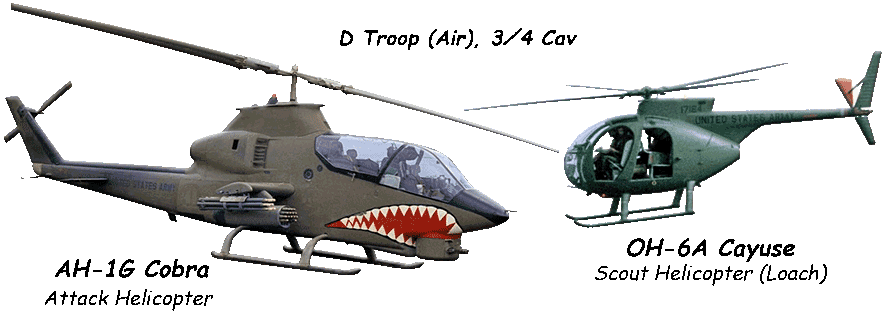

So off to flight school I went — spending the better part of 1968 learning how to fly Army helicopters. First stop was Ft. Wolters in Texas (near Ft. Worth) where we went through Pre- Flight Training and Primary Flight Training. I was assigned to train in the OH-13 (the Bell Helicopter Model 47) like the ones made famous in the “MASH” movie and television series. All of the academics and actual hands-on training was very challenging as well as a lot of fun. My first instructor pilot cheerfully pointed out the manufacturer data plate on the first helicopter I flew – the helicopter was a year older than I was. From Ft. Wolters I went on Ft. Rucker in Southeastern Alabama for Instrument Flight Training (again in the OH-13), transition to turbine helicopters the famous UH-1 Iroquois (the Bell Helicopter Models 204 and 205) Huey and then on to tactical training (formation flying, confined area operations, more emergency training, etc.) As I mentioned earlier, I was a reasonably good test taker, so I ranked in the top 10 of a class of about 200 and was selected to attend advanced training at Hunter Army Airfield in Savanah GA for the AH-1G Cobra Attack Helicopter.

So off to flight school I went — spending the better part of 1968 learning how to fly Army helicopters. First stop was Ft. Wolters in Texas (near Ft. Worth) where we went through Pre- Flight Training and Primary Flight Training. I was assigned to train in the OH-13 (the Bell Helicopter Model 47) like the ones made famous in the “MASH” movie and television series. All of the academics and actual hands-on training was very challenging as well as a lot of fun. My first instructor pilot cheerfully pointed out the manufacturer data plate on the first helicopter I flew – the helicopter was a year older than I was. From Ft. Wolters I went on Ft. Rucker in Southeastern Alabama for Instrument Flight Training (again in the OH-13), transition to turbine helicopters the famous UH-1 Iroquois (the Bell Helicopter Models 204 and 205) Huey and then on to tactical training (formation flying, confined area operations, more emergency training, etc.) As I mentioned earlier, I was a reasonably good test taker, so I ranked in the top 10 of a class of about 200 and was selected to attend advanced training at Hunter Army Airfield in Savanah GA for the AH-1G Cobra Attack Helicopter.

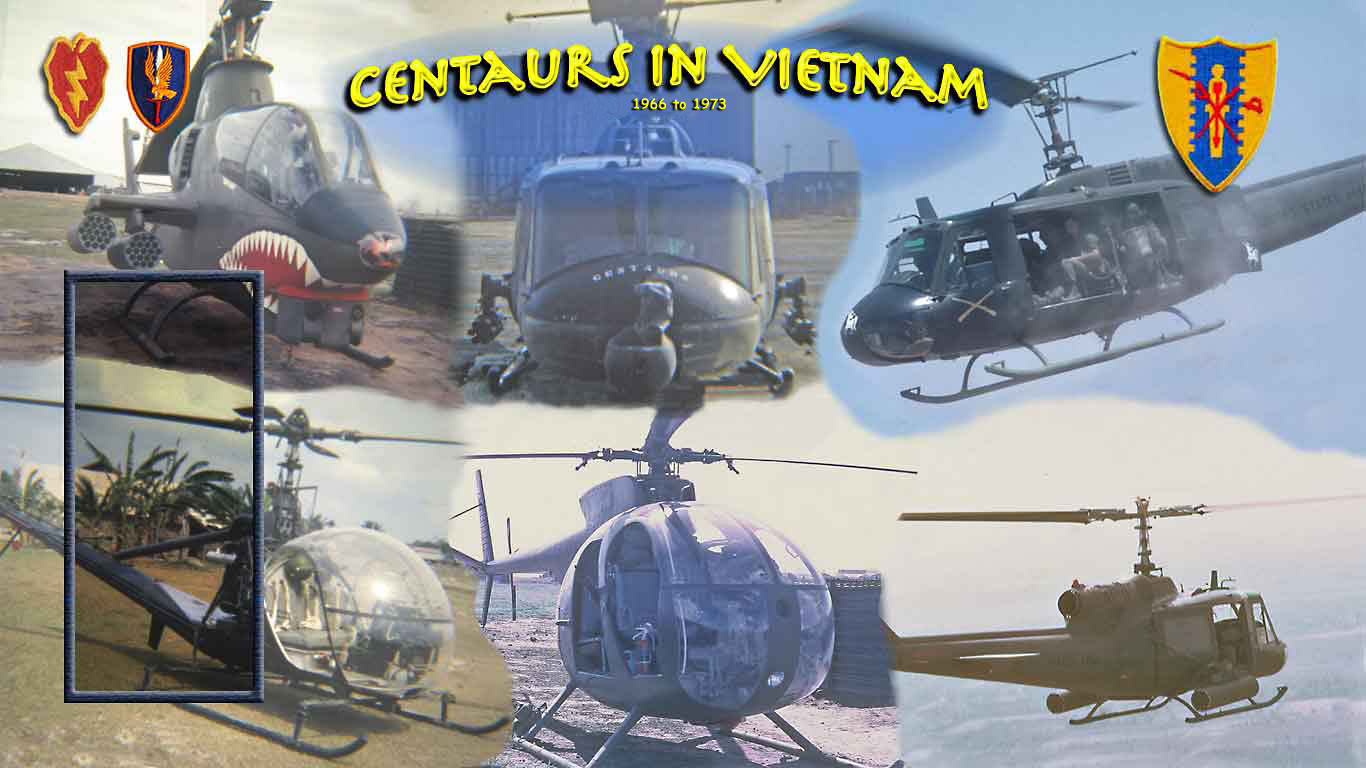

I arrived in Vietnam in January 1969, was in-processed at Bien Hoa replacement depot (we’re not in Kansas anymore, Toto) and sent on to the 25th Infantry Division headquartered at the Cu Chi basecamp about 30 kilometers (20 miles) Northwest of Saigon. Once I in-processed at the 25th Division, I was assigned to D Troop (Air), Third Squadron, Fourth Cavalry. Each Infantry Division in Vietnam was assigned a Cavalry Squadron to round out their forces, supplementing the Division with three armored troops and an air troop.

D Troop had a number of different missions – Visual Reconnaissance (VR), Close Air support for troops in contact, medevac, resupply, troop lifts, ready reaction team, etc. In other words, other than heavy lift missions by the larger aircraft (CH-47 and CH-54 Skycranes), we did everything. The VR teams were made up of an AH-1G Cobra (Photo) and an OH-6A Loach (Photo). The Loach would fly low level looking for enemy activity on the ground, while the Cobra provided overwatch, covering the Loach with its armament systems.

I went through the normal progression from Fucking New Guy (FNG) to Peter Pilot to Aircraft Commander and Fire Team Leader (even tucked an Instructor Pilot rating under my belt in there somehow), and by the time this story begins, I was one of the more senior Cobra pilots in the troop.

The Mission - October 28, 1969

It started out as a typical day, where the Troop fielded six Visual Reconnaissance teams — two assigned to support Cu Chi basecamp units, two to support Tay Ninh basecamp units, and the remaining two to support as needed in the 25th area of operations.

My team was made up of myself (Sam Dooling) as Team Leader/Cobra Aircraft Commander, my Pilot/Gunner Warrant Officer Jack Craig and our Scout, 1st Lieutenant Mark Jackson and his Crew Chief and Observer/Gunner in the OH-6A Loach.

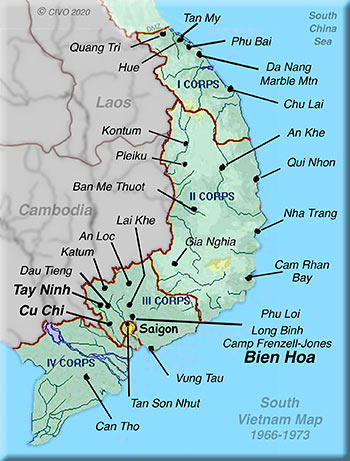

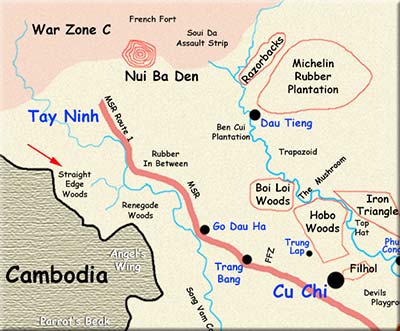

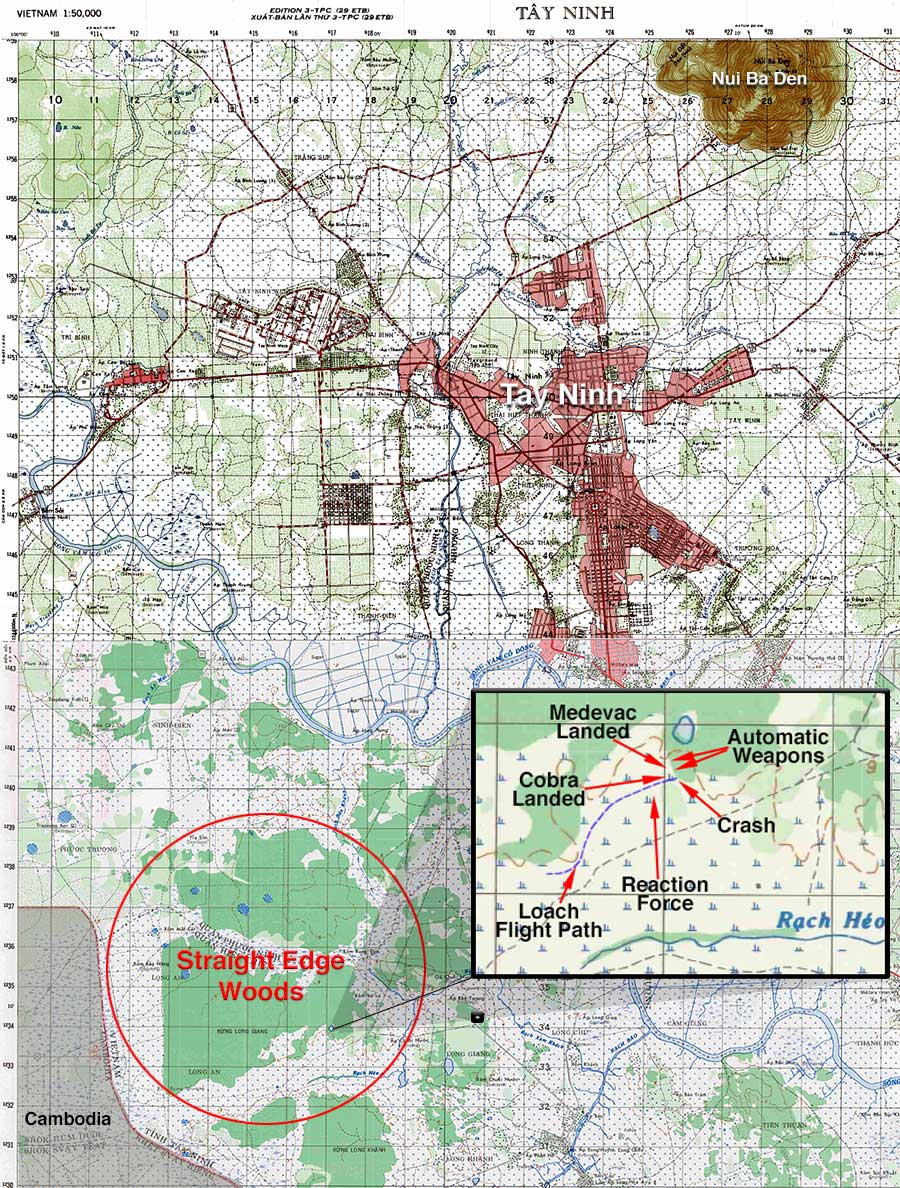

We departed Cu Chi (our main base) at sunrise and flew to Tay Ninh about 65 kilometers (40 miles) Northwest of Cu Chi to start our support. When we reported to the Tactical Operation Center (TOC) at Tay Ninh, they assigned our team to do a VR of an area commonly referred to as the Straight Edge Woods, about 15 kilometers (10 miles) south of Tay Ninh.

We departed Cu Chi (our main base) at sunrise and flew to Tay Ninh about 65 kilometers (40 miles) Northwest of Cu Chi to start our support. When we reported to the Tactical Operation Center (TOC) at Tay Ninh, they assigned our team to do a VR of an area commonly referred to as the Straight Edge Woods, about 15 kilometers (10 miles) south of Tay Ninh.

The Straight Edge Woods (see Maps) were located on the border between Vietnam and Cambodia. The Army had placed a number of electronic “sniffer” and “motion” sensors in this double/triple canopy jungle area and they were getting a lot of indications of personnel activity, so they wanted to us to go take a look.

We refueled at Tay Ninh and headed to our assigned area, arriving around 0900. We began our recon by having Mark descend to low level (10 to 20 feet off the ground) on the North side of the jungle area, then move around the forest perimeter in a counter-clockwise direction. We flew around the perimeter of the jungle and Mark would make flights into the interior of the jungle area when he noted potential activity (trails, smoke from fires, etc.). As per normal operating procedures, I flew wide circles around Mark at an altitude of 1,500 feet keeping track of where he was, giving him guidance on places to look over our internal radio frequency, and staying in a position where I could provide immediate response to him taking enemy fire with my miniguns, a grenade launcher, and 2.75” rockets.

While we were doing our recon, an Air Force Forward Air Controller (FAC) contacted us to see if we had found anything and if we needed his support (FACs are Air Force guys that fly around in smaller airplanes to find and mark targets for their fast movers – like F-4s, F-100s, etc. to drop bombs and napalm). We had worked our way around the Strait Edge Woods to the southeast corner (see Map 3) and both aircraft were getting low on fuel. I called Mark to tell him to come up to altitude and head back to Tay Ninh for fuel. He responded that he was following a recent trail through the grass flatland and wanted to check it out — the trail was so prominent that we could see it from 1,500 feet.

The trail led directly up to a wall of trees that were about 75 feet – 100 feet tall. As Mark

approached the trees at about 60 knots (70 miles per hour), I expected him to do a climb up to the top of the trees, but instead, he flew directly into the trees and crashed. The crash site was about 75 to 100 meters south of where the trail entered the trees. Neither Jack nor I had observed any weapons firing from the trees or the Loach, so we were unclear as to whether Mark had been shot down or if he just crashed. As a matter of caution (in case he had been shot down), I fired most of my rockets into the tree line where the trail entered to ensure anyone on the ground would keep their head down.

At the time of the crash, I was directly south of the crash site, so my rocket run took me just east of the crash, headed north. I pulled out of my rocket run and completed a 180-degree turn (headed south now about 200 meters west of the tree line) and slowed to about 20 knots at 50’ altitude to inspect the crash site and look for survivors. Just as I was about 150 meters north of the crash site, the enemy opened up with automatic weapons from the tree line, and we had several streams of yellow/green tracers passing in front of and under the Cobra. This particular Cobra was configured with M18E1 Minigun pods on the inboard pilons (Cobras had two hardpoints, or pilons, on each wing – see photo). In this configuration, we had 19 tube rocket pods outboard and miniguns inboard, so I pulled the Cobra to a high hover, made a 90-degree left peddle turn into the enemy machine guns, and emptied both of the minigun pods into the tree line — probably not the smartest move, but I was pretty pissed. First, they shoot down my Loach, then they try to shoot me down!

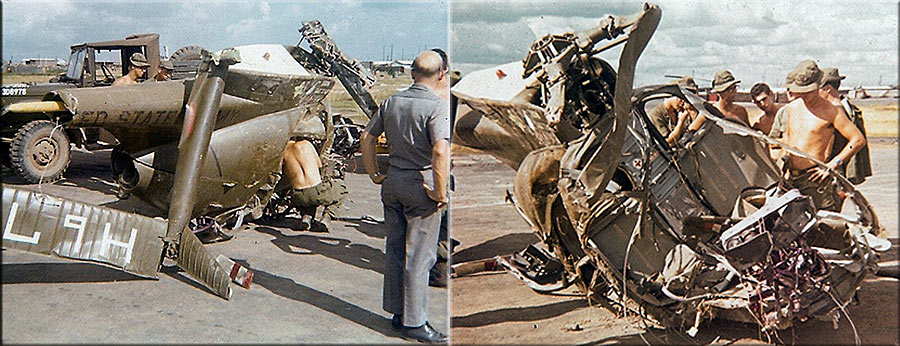

Between the rockets and the miniguns, the enemy decided to quit firing. We hovered the Cobra over nearer to the Loach. The Loach had hit a large hardwood tree head-on, directly in alignment with the right front seat of the airframe. The Loach had spun around the tree and was laying on its right side facing back the way it had come from. The Observer was standing on the side of the Loach waving at us.

Between the rockets and the miniguns, the enemy decided to quit firing. We hovered the Cobra over nearer to the Loach. The Loach had hit a large hardwood tree head-on, directly in alignment with the right front seat of the airframe. The Loach had spun around the tree and was laying on its right side facing back the way it had come from. The Observer was standing on the side of the Loach waving at us.

All this time, I had been talking to the Tay Ninh TOC on the radio and requesting gunship support, medevac, and a ready reaction team to come help out. I was also coordinating with the Air Force FAC (he was also on the TOC frequency) and he was relaying my transmissions once I was on the ground. We landed about 75 meters from the crashed Loach and Jack hopped out of the Cobra’s front seat to assist the guys in the Loach. Just as Jack was stepping down from the side of the Cobra, I noticed that there was a small fire in the Loach’s engine compartment, and I yelled to Jack to grab the fire extinguisher.

Jack did one of the bravest things I saw in Vietnam — he grabbed the fire extinguisher and

ran across the 75 meters of open flat ground knowing that an enemy was only about 150 meters away with automatic weapons, yet still choosing to run toward a burning aircraft loaded with fuel and explosive devices, while carrying a fairly puny fire extinguisher.

The crash had torn up the ground between us and the Loach and the aluminum rotor blades were shredded all around the crash site – Jack tripped on the torn-up ground and fell to his knees right on top of a sharp edge of a rotor blade, giving each knee a pretty good slice. Ignoring his injuries, he extinguished the fire, which certainly saved the Crew Chief’s life as he was trapped under the aircraft lying in a puddle of fuel.

By this time, I had confirmed that the reaction forces were on their way, so I secured the Cobra and ran to the crash scene. We checked out the Observer; he was fairly shook up and had been shot in the left elbow. We got him calmed dodiamondwn, and he and Jack took up defensive positions behind a small berm facing the area from where the enemy had fired. Our total complement of weapons at that time were the Observer’s M-16, Jack’s 38 pistol, and my 38. I traded my 38 to the Observer for the M-16 and its 20-round magazine, gave the M-16 to Jack, and then I went to check on the Crew Chief and Mark. I called out to the Crew Chief and he called back from underneath the aircraft stating he was injured and pinned under the aircraft. The Crew Chief’s position in the aircraft is in the right-rear seat, so, with the aircraft lying on its right side, he was trapped underneath.

I crawled under the aircraft to evaluate the Crew Chief’s situation. The mount for the swivel minigun had his right leg pinned to the ground. His femur was clearly broken and he was pretty roughed up. I told him I would be right back after I checked on Mark, who was still in the pilot’s seat which was crushed into the mud and inaccessible from where I was. (The pilot’s seat is directly in front of the Crew Chief’s in the Loach, but because of how the aircraft had hit the tree and then smashed into the ground, it was completely inaccessible from under the aircraft.) I had to crawl back out from under the aircraft and climb to the top, which was now the left side of the aircraft facing up. I squirmed my way into the cockpit to Mark, but to no avail. He

had been shot in the head and was clearly dead.

I returned to the Crew Chief, and, laying in a puddle of water and fuel, dug a hole under his trapped leg with my hands, got him loose from the aircraft, and dragged him away from the wreckage. Just as we were moving away from the wreck, Jack called out that the Medevac had arrived; our first arrival of assistance. It was now crash plus about 20 minutes, but it seemed like we’d been on the ground all day.

As I dragged the Crew Chief over to the berm where the Observer and Jack were, I noted the Medevac on short final – LANDING RIGHT IN FRONT OF WHERE THE ENEMY MACHINE GUNS HAD BEEN! Fortunately, our rockets and miniguns must have thoroughly discouraged the bad guys, and the Medevac did not take any fire.

Jack’s knees were fairly messed up, the Observer was not tracking too well (big wonder), so it was up to me to get the Crew Chief over to the Medevac about 75 meters away. Although I was a reasonably tall guy by then (6 feet), at just 135 pounds I was not what you would call stout. But stout did apply to the Crew Chief. Well, you work with what you’ve got. I somehow managed to get the 175 lb. Crew Chief onto my shoulder in a fireman’s carry and started running with him toward the Medevac — you remember, the one sitting in front of the enemy’s machine guns. I had the Observer follow me. By the time I got about 25 meters from the Medevac, I swear the Crew Chief’s weight had increased to 300 lbs., and the two crewmen from the medevac finally met me with a stretcher. We loaded the Crew Chief onto the stretcher, and they took him and the Observer the rest of the way to the medevac aircraft.

I started back to the crash site, but heard someone yelling. I turned to find one of the medevac crew members running after me with my 38, the one I had loaned the Observer. Once again, I was armed and dangerous(?). I went back over to where Jack was holding the fort, and the Medevac took off.

Keep in mind, that once Jack and I left the Cobra, we were out of contact with everyone. We didn’t really know what was going on or when the reaction force would arrive; we could see the FAC circling, but that was it. When the Medevac left, it got realllllly quiet. Fortunately, that only lasted for a few minutes. The next arrivals were a pair of 25th Aviation Company (callsign Diamondback) Charlie Model Huey gunships. They came right over the top of us and started spraying down the tree line with M-60 fire (I guess the FAC told them where the bad guys were). I loved those guys.

Keep in mind, that once Jack and I left the Cobra, we were out of contact with everyone. We didn’t really know what was going on or when the reaction force would arrive; we could see the FAC circling, but that was it. When the Medevac left, it got realllllly quiet. Fortunately, that only lasted for a few minutes. The next arrivals were a pair of 25th Aviation Company (callsign Diamondback) Charlie Model Huey gunships. They came right over the top of us and started spraying down the tree line with M-60 fire (I guess the FAC told them where the bad guys were). I loved those guys.

Unwilling to leave Mark’s body, Jack and I hunkered down by the berm, Jack watching one way and me the other. If you note on Map 4, southwest of the crash site is a stand of scrub brush (light green shading). We could not see to the other side of the scrub brush from our position, and with all the welcome noise the Charlie Models were making, we did not hear the reaction force Huey sit down on the far side of the scrub. As I was observing over toward the Cobra, movement caught my eye; it was a Vietnamese solder in full combat gear coming around the north end of the scrub. I was just about to start shooting at him when I noticed a couple of good ol’ American GI’s right behind him! He was what they called a Kit Carson Scout — a Viet Cong that had changed sides to work with the Americans. The reaction force had arrived. We were probably crash plus 30 minutes at this point. We briefed the platoon sergeant on the situation, and he had his guys extract Mark’s body from the Loach and secure the area.

Now if you remember, the entire crash scenario started when we had announced we were low on fuel. The Cobra had been sitting idling for the entire time we were on the ground. Jack and I returned to the Cobra to get ourselves back to a basecamp — any basecamp. Jack was banged up and his knees were still bleeding. I was pretty frazzled myself, not to mention soaked with fuel from laying under the crashed Loach. We strapped back into the Cobra and I looked down and saw we had less than 150 lbs. of fuel left, or about 10 to 15 minutes of flight time. Not enough to get us to home base (Cu Chi), but hopefully enough to get us back to Tay Ninh. Once we took off, the 20-minute fuel low light illuminated immediately, so we hauled ass back to Tay Ninh refueling point. We made it, refueled, and moved the aircraft over to the TOC pads. That is where we discovered that even though the bad guys were pretty poor shots when shooting at a Cobra, they hadn’t been completely useless. We had a couple of holes in the tail boom.

After checking the aircraft out and determining that the holes were not through anything critical, we were cleared to return to Cu Chi.

At Cu Chi, Jack went over and got his knees patched up plus a shower and change of clothes. I took a long (cold) shower and changed into a new flight suite. Our platoon leader brought us some after-action forms to fill in, and then advised me that since we were short of night- qualified fire team leaders, I would need to sit my butt back into a different Cobra with a different pilot and head back to Tay Ninh to pull night fire team support.

It really wasn’t so bad. The Tay Ninh operations officer took pretty good care of us, and he got us fed. We did our standby in the TOC officer’s club, and the AF FAC came by to shake my hand and buy me a drink (Coke, even though I was a die-hard Pepsi man).

As you can see from the ‘after’ photos of the Iron Butterfly below, the collision with the trees was pretty violent. Even now I’m amazed at how much damage the OH-6A aircraft could take and still protect the crew. I participated in a couple of OH-6 crashes personally, and I witnessed several more from flying cover in a Cobra, including one where the aircraft literally blew up about 15 feet off the ground traveling at 80 knots. Yet each time, the aircraft always seemed to magically protect its occupants.

The passing of Mark Jackson was indeed a sad event. Like many of us, he was just starting his adult life; he was only 21 years old. He had been in country a scant 4 months. It was not until years later that I learned that Jack Craig and Mark had gone through flight school together, then to Cobra transition. Hell, they even flew to Vietnam on the same airplane. Losing someone who shares those experiences hurts — and that ain’t no bullshit.

Both Jack and I received Silver Stars for our contributions. Jack also received a Purple Heart for the injuries he received during the rescue.

............................AWARD OF THE SILVER STAR..................................

DOOLING, THOMAS M. CW2 USA

D Troop 3rd Squadron, 4th Cavalry, 25th Infantry Div

Awarded: Silver Star

Date action: 28 October 1969

Theater- Republic of Vietnam

Reason:

For gallantry in action: Chief Warrant Officer Dooling distinguished himself by heroic actions on 28 October 1969, while serving as an Aircraft Commander with D Troop, 3d Squadron, 4th Cavalry in the Republic of Vietnam. Warrant Officer Dooling’s aircraft was flying cover for a light observation helicopter, when that ship was hit by small arms fire and crashed, killing the pilot and wounding the crew members. Immediately, Warrant Officer Dooling placed accurate suppressive fire on the insurgents. While making a pass to determine, the condition of the downed ship's crew, Warrant Officer Dooling's aircraft was damaged by enemy ground fire. Without hesitation, he made a firing pass at the aggressors and silenced their position. Disregarding the presence of the enemy in the area, Warrant Officer Dooling landed his aircraft in order to assist his wounded comrades. Upon landing, he immediately dispatched his pilot to the downed aircraft as he remained in his ship to coordinate incoming support forces. When he was assured that help was on the way, Warrant Officer Dooling left his aircraft and aided his pilot in treating the wounded and evacuating them to safety. His valorous actions were responsible for saving several lives. Warrant Officer Dooling's bravery, aggressiveness, and devotion to duty are in keeping with the highest traditions of the military service and reflect great credit upon himself his unit, the 25th Infantry Division, and the United States Army.

Authority: By direction of the President, under the provisions of the Act of Congress, approved 9 July 1918, AR 672-5-19 and USARV Reg. 672-1.

16