The Jesus Nut

This article was published in the The VHPA Aviator, July/August 2012

Mentioned in the story are Lloyd Allred, Harlen Cooper, Gene Prosser, John Alto, and Mike Squires

"There are objects given to us by divinity

Without which we begin our journey in eternity."

click speaker button for song

My first exposure to the “Jesus nut” was fifty-three years ago during OH-23 transition training. Can it be that long? It is a term that has special meaning to chopper crewmen. During training in Class 59-6 at Camp Wolters, Texas, I recall climbing the OH-23 mast, checking those two little air foils, paddles they were called.

These in turn controlled the main rotorblades. I examined all those very necessary wiggling, rotating, and oscillating linkages and mechanisms with a silent curiosity, “What the hell really holds all this on the mast?” The instructors would say, “Be sure and check the Jesus nut”. Well, of course, it did not really exist. They were imprinting our memory. One or all of those little nuts and bolts held a lot of pieces together that made the contraption fly.

Through my twenty-two active flying years, I would often call out to a comrade pre-flighting, “Don’t forget the Jesus nut!”. It was a friendly reminder to be thorough. Could an aircraft nut come off? Well, not unless there were some extenuating circumstances. Nearly every nut on an aircraft has a safety wire insuring that, even loose, it cannot unscrew.

What image or construct does “Jesus” nut conger up in the minds of other chopper pilots? In my mind it’s the last fastener, a big one, on a whole stack of rotating parts that keeps everything from departing. Even though I know that there is really no such nut, I have a mental image of this ultimate hex nut that kept me safely in the sky.

"Amen, I say To you Faithful warrior

There are many on the helicopter you fly.

The Jesus nut – you know not which.

It is you I charge to check them all.

But it is mine without which you will fall.

Amen, I say"

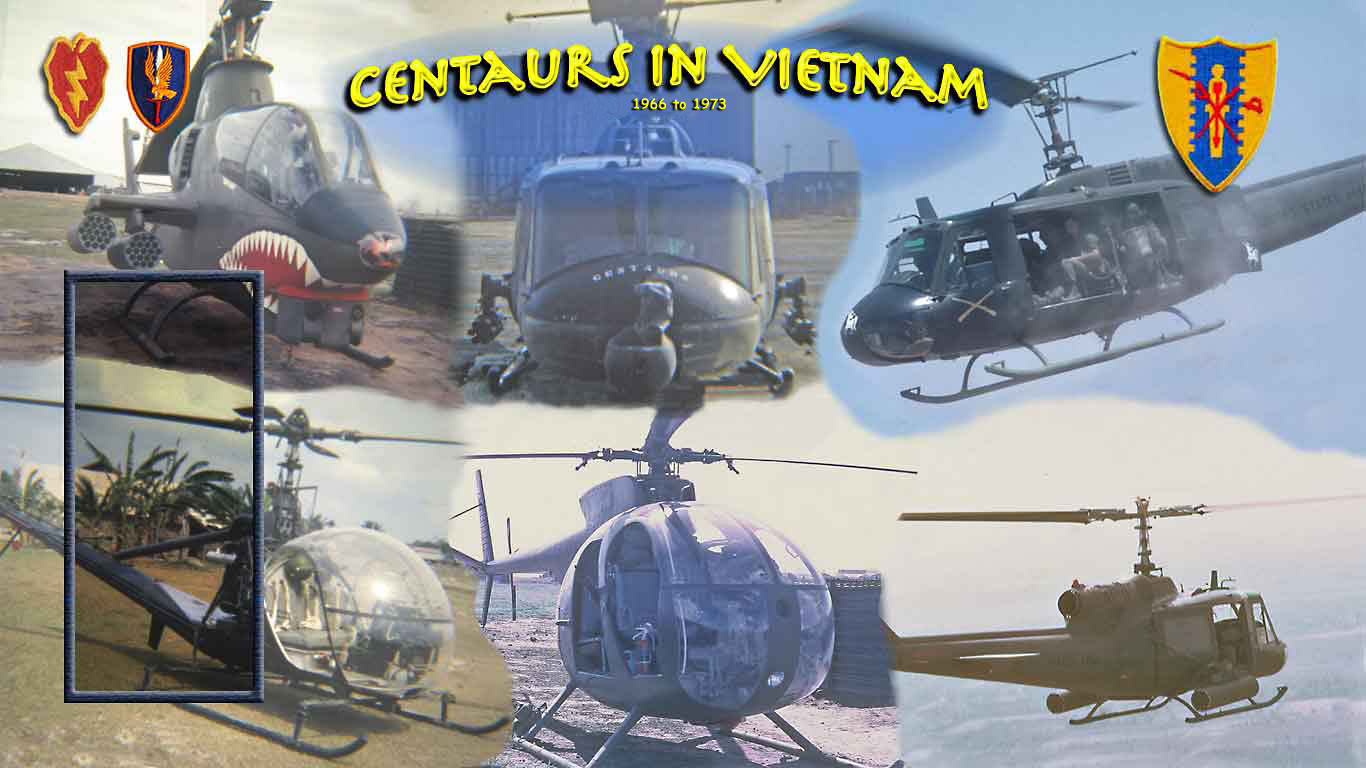

Slow forward seven years, a couple of thousand flying hours, to 1966 and the Centaurs of D Troop (Air Cavalry), 3rd Squadron, 4th Cavalry Regiment, who are in possession of the only resident gunships on the 25th Division Base Camp, Cu Chu, South Vietnam. During most of 1966, the troop’s four hogs and six heavy scouts were their new quick reaction direct air support. Centaur fire teams were committed, providing Base Camp Alert. Missions snapped by phone and radio to the operations center at all hours of the day and night. Nearly every qualified gunship aviator was on the roster. The team scrambled while lives depended upon them.

Aircraft preflight inspection fully completed, switches set, personal gear stowed, everything correct and ready. When your crew is squared away, things go smoothly. The goal; lying on the bunk or sitting in operations, is to pull pitch two minutes after the horn. The high alert status keeps individuals sharp and teams organized.

One April midnight I hit the left seat; LT Allred, without yet strapping, had the turbine coming up to full RPM. I quickly strapped in; the needles joined; I keyed the intercom, “coming up”. LT Allred strapped in as I gingerly hovered the maximum gross weight Hog to the takeoff pad. At the pad I heard my wingman request clearance, and I turned the controls back to Allred for takeoff, so I could record the mission details from the Centaur Operations.

The scramble to the big horn was a call from a fortified hamlet near Bo Tri, along Highway 10, that ran southwest of Saigon. The small Republic of Vietnam local force defense was no more than twenty minutes southeast of CuChi in wet country. This classic triangular fortification of bunkers and barbedwire was where the local forces hankered down at night and largely let the VietCong roam. All the crews had visited this one on a routine “keep acquainted” tour of similar local force defensive areas in the division operational area.

We put the few lights of Cu Chi behind. That night 81mm illuminating rounds floated in the distant sky.The1966 countryside belonged to the VC at night. Highway traffic did not exist, everyone in bed and the lights out. The local VC was relentlessly restless after dark. These very small fortifications were quite easy to find with a firefight in progress. Sparkling tracers would float in and out; there were bright flashes of grenades and mortars. It was a great lightshow from above.

The RVN local force systematically marked the attacking VC as we coordinated directly on the local FM command net. By the intersecting fire of two machine guns’ tracers or an illuminating flair, they quickly designated targets. Allred led the fire team parallel to the defensive barbed wire as I triggered off the 40mm grenade launcher with its rhythmic thumpa-thumpa, followed by the wingman’s quad 7.62 machineguns where the current attack was inprogress. We were working too close to the defense for the irregularities of the rockets; plus, they destroyed the intricately laid barbed wire. Remember those high tech rocket system sights; a personalized, custom inscribed, grease pencilmark on the wind screen?

This was where the door gunners do their artful work on individual muzzle flashes, just devastatingly accurate fire at the low end of a firing dive. On the break, WHAM! It’s like the sound of a hammer hitting the chopper body! I pressed the mike, “Taking a hit.” Immediately on intercom the high door gun muttered tersely, “Damn, I think I hit the skid. The SOB was right under us, sorry!” “No worry”, on to the nearby wood line. Three good rocket runs expend all our rockets in the VC assembly area.

All finished our gross weight now light. With only a few machine gun rounds in emergency reserve, we headed back to Cu Chi. There had been plenty of ground action and many little meteor-like tracer streaks, sparkling little spirals intended for us. We had not received a single hit. A productive mission was about to close.

As the team turned northwest, the dim lights of Cu Chi appeared as a very thin line on the horizon. At a light gross weight, I encouraged LT Allred to “hitch it up to 120 knots, and let’s get home.” As the airspeed touched 110, the UH-1B suddenly began to violently oscillate vertically. This was not an action similar to an out-of-balance front tire that one felt through the seat of his pants. This was strong: strong enough to make one’s helmet flop. I grabbed the controls and started to gingerly decelerate. I pressed the mike, “Taking it down to the ground.” Night or not, I preferred being parked in a hostile paddy to falling out of the sky.

The whole crew was doing an instant analysis of our dilemma. We had not taken any hits, lots of unremembered intercom chatter. The crew chief had the facts; our very strong 540 rotor system had a violent one per rev vertical vibration. Of course, we were ignorant of the true cause. Airborne at night a prognosis like that is pretty open ended. Then someone muttered, “God, I hope the Jesus nut doesn’t come off.” It’s that image! As we decelerated below 60 knots, again everything became smooth. It was instantly peaceful, just the quite low mellow hum of the turbine.

"The Jesus Nut!

One-to-one vertical vibrations

Not a pleasant sensation.

At night it caused the crew serious consternation."

Our wingman quickly moved forward alongside in a closer formation. I explained the situation and ordered them to keep us covered, making sure they were also in communications with the Centaur CP. I confirmed that if neces- sary, to be prepared to pick up the four of us if we had to set down in a hostile paddy. With the vibration gone, it was a slow, but smooth ride at 60 knots. A landing in nowhere was now absolutely inappropriate. Centaur Operations confirmed the alert status of the backup gun team. I asked for the troop aircraft maintenance sergeant on the radio. Even at 02:00 in the morning it was like SSG Cooper had been standing in operations waiting for our call. He, the crew chief, and I had a brief exchange. I returned the controls to LT Allred, and we settled in at a steady 40 knots.

We concluded that the chopper would not fall out of the sky if we flew slowly. No one had to tell me to fly slowly, but it was consoling to know that every one agreed. That “Jesus nut”, believe me, I had this image of that “ultimate hex nut” coming off at night in the middle of nowhere. Flying slowly onward we were one highly tuned, attentive crew.

Being a little apprehensive, I requested an initial landing spot well clear of all other parked choppers. Ready for the worst, my fire team smoothly, but slowly, hovered to the Cu Chi Centaur Corral and the waiting maintenance crew.

As I clicked off the master switch I gave the crew an aggressive thumbs up and a loud, “YES, on the ground again!” I checked through operations: there was MAJ Prosser, the XO, and the next scramble gun team at the ready if we had called. LT Alto, the Aero Rifle Platoon Leader, and MAJ Squires, the slick platoon lead, were there ready to move to alert status. Backup like that let me know I did not need to worry about no one caring. Another interesting night flight in Vietnam!

The following day I cornered SSG Cooper to examine the bucking B model 540 hub. I wanted a piece-by-piece analysis of what had happened. In this case, the collective sleeve was loose. How should we have known? I also confirmed that there were a number of nuts holding all that stuff together. I’m still not sure which one is the Jesus nut.

I should have known! In my little UH-1B Pilot’s Pocket Information Manual, it says all the below may be found to be the cause of 1-to-1 vertical vibrations:

I should have known! In my little UH-1B Pilot’s Pocket Information Manual, it says all the below may be found to be the cause of 1-to-1 vertical vibrations:

Grips rolled incorrectly

Trim Tabs

Push pull tubes bent

Stabilizer bar out tube bent

Collective sleeve loose

Collective hub bearing loose

Rotor blade leading edge loose

Transmission mounts defective

"If I know all this is OK while I fly,

I will not fall out of the sky?"

Copyright March 2015 Robert L Graham