Battle of Suoi Tre Reunion and Memorial

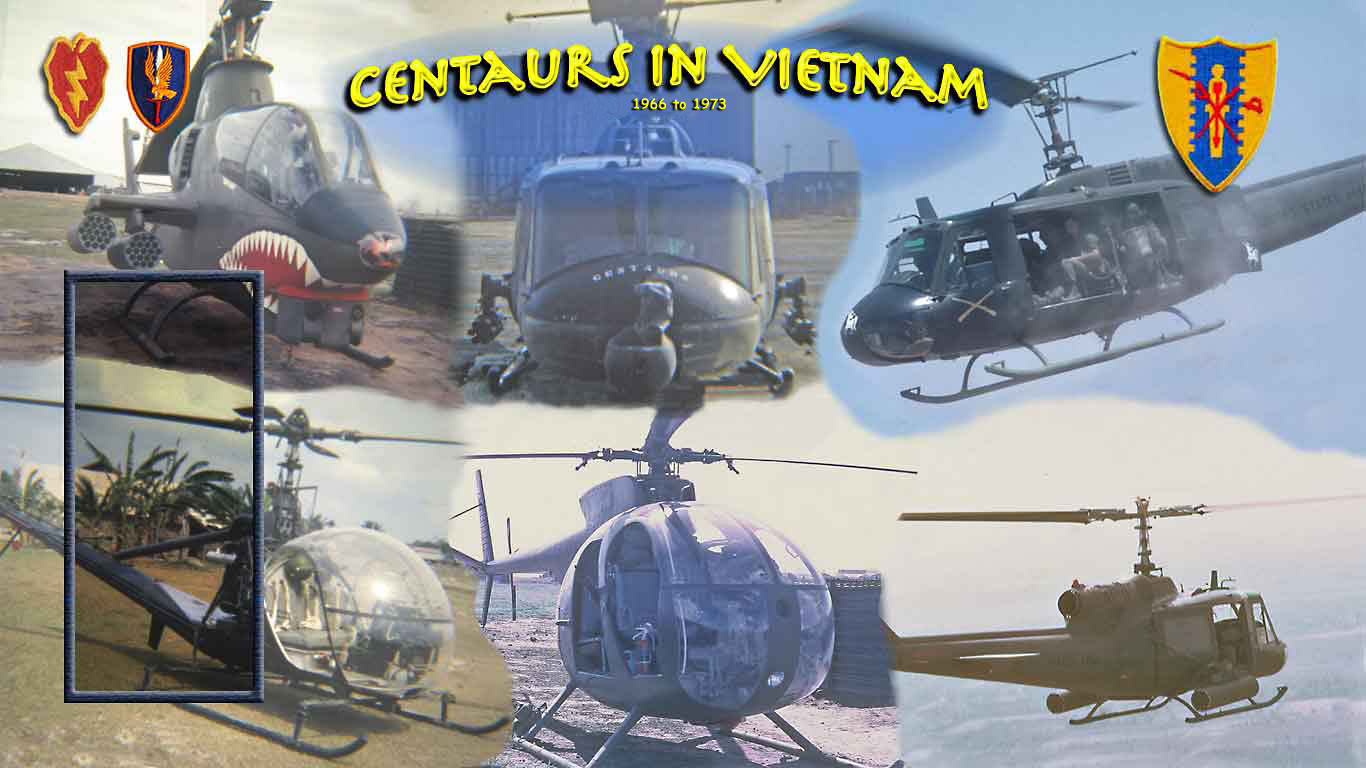

Reminiscences of the Centaurs, D Troop (Air), 3rd Squadron, 4th Cavalry, 25th Infantry Division

Presentation written/edited by then-First Lieutenant Bain Cowell, Artillery forward observer attached to D Troop

For delivery at the Reunion by then-Major George J. Stenehjem, former Centaur 6, Colonel (Retired)

A daughter of one of George’s West Point 1954 classmates delivered the speech on March 20, 2015, since he had taken ill.

(also see the Battle of Suoi Tre page)

Copyright, Bainbridge Cowell Jr., March 2015

The Centaurs were an Air Cavalry troop of helicopters and infantry assigned to the “Three-Quarter Cav,” the 25th Division’s armored cavalry squadron. In March 1967, I had just assumed command of the Air Cavalry troop. During Operation Junction City, Centaur helicopters inserted Long Range Reconnaissance Patrols (LRRPs) in the jungle to detect enemy movements along the eastern flank of War Zone C as U.S. armored and mechanized forces drove north. Our helicopters were standing by at Tay Ninh to insert, support ,and extract the LRRPs if they made contact. One of the patrols warned of a possible attack on Landing Zone Gold.

At dawn on 21 March the Centaurs became multitaskers. We had to continue supporting recon patrols while responding to the crisis at LZ Gold. I got a request from the Air Force to rescue a forward air controller L-19 spotter plane that had been shot down. I radioed the Service Platoon Leader, Captain Tom Fleming, to crank up the maintenance and recovery helicopter, a Huey nicknamed “Stable Boy,” and four Huey gunships to search for the lost aircraft. Tom, looking for the L-19, spotted tanks crashing through the jungle; a kilometer away he saw “an immense conflagration” of air strikes and exploding artillery rounds on LZ Gold. Soon I took off in my command-and-control Huey with my crew of four. Looking north past Nui Ba Den I was startled to see a mass of gray smoke pouring out of the jungle.

Meanwhile, another Centaur “slick” commanded by the Aerorifle Platoon Leader, Major Harold Fisher, was already in the air to get a situation report from a recon patrol. But he saw the smoke and explosions at LZ Gold, and D Troop Operations told him that scores of wounded GIs needed medical evacuation. He and his crew immediately volunteered, no matter what the risk. As they circled in a holding pattern and listened to frantic radio transmissions from ground troops shouting that they were being overrun and their howitzers destroyed, the Centaurs wondered if they could survive a descent into that inferno.

On their final approach under low clouds, they ran an obstacle course of incoming mortars, outgoing artillery, close-in airstrikes, and the risk of being targeted by the enemy. Upon landing, they encountered a “thousand-yard stare” of exhausted troops who had fought for hours, unflinching as they calmly loaded their wounded onto the chopper despite incoming fire all around.

Service Platoon Leader Fleming, unable to find the downed Air Force plane, repositioned his chopper for medevacs. He headed in at treetop level amid mortar, RPG, and machinegun fire, almost collided with then-Lieutenant Colonel John Vessey’s small C&C helicopter, and landed near the exploding ammo dump and smoldering wreckage of two Hueys.

On the ground “everyone was in holes or crawling around.” They began dragging the wounded to the medevac helicopter. As each severely wounded man was lifted into one side of the ship, a less-wounded man would get out the other side. Then Tom saw a nearby quad .50 machinegun, “its barrels jammed and overrun with VC, blown away by direct fire from a howitzer,” and U.S. infantrymen firing from behind VC corpses. As he pulled his loaded Huey up, U.S. armored personnel carriers burst from a tree line and drove into the ranks of attacking VC.

Stable Boy delivered the casualties to the Army hospital at Tay Ninh and returned for a second medevac run. On a third trip they learned the location of the Air Force crash site south of LZ Gold. Eight Centaur gunships made daisy-chain gun runs around the site to protect Stable Boy as it hovered over the wreck and lowered medic SSG Kelly 75 feet on a rescue hoist. Kelly found two decapitated bodies and the Centaurs informed the Air Force. U.S. ground forces later retrieved the remains.

During the medevacs, the Centaur crews worked to keep the wounded alive en route to the hospital. Lieutenant Colonel John Bender, commanding the Second of the Twelfth Infantry, directed the medevac crews to casualties on the ground. On Fisher’s “slick,” a soldier with an abdominal wound cried out for water, but crew chief Specialist Mike Vaughn, trained in first aid, correctly said no. The man was in traumatic shock, so aircraft commander Fisher took off his own shirt to be used as a blanket. Another man with a gaping thigh wound asked to die because his girlfriend wouldn’t like him anymore; the crew chief and gunner encouraged him to hang on and pull through. All told, Fisher and his crew made three trips and carried a dozen WIAs to hospitals at Tay Ninh and Bien Hoa.

With mortar and small-arms fire still coming into the LZ, the Stable Boy crew was asked to medevac a wounded VC prisoner as a priority -- requiring other casualties to be off-loaded -- and also medevac a badly wounded U.S. soldier from a listening post. Fleming hovered his ship across the LZ beyond the perimeter to locate and pick up the wounded GI, who had lost both legs and an arm and had a sucking chest wound. After takeoff this soldier tried to push the VC prisoner out the door, but was restrained by our medic. Both patients later died.

The Centaurs’ gunships came back repeatedly to support the ground units and protect medevac choppers. Some of the gunships were diverted from other missions. Pilot Rick Arthur, 20 years old with only three weeks in country, and a light fire team of two Hueys armed with rockets, flex machineguns, and a grenade launcher had just finished an all-night standby on counter-mortar duty at the Dau Tieng airstrip. As they prepared to return to Cu Chi, a crewman from a Chinook helicopter at the refueling point asked the Centaurs to escort his big bird loaded with howitzer ammo into a hot LZ not far away. The Centaur crews agreed and followed the Chinook, which made it in, unloaded, and departed. “All hell was on the radio,” Rick recalled, so “there was no way to coordinate and we held our fire.” Watching the airstrikes and artillery, “we simply picked the common target and fired our load of rockets on it.”

The Centaurs’ artillery observer, First Lieutenant Bain Cowell, was riding with me, but didn’t fire a shot at LZ Gold; many artillerymen on the ground were doing that. Instead he helped me keep the Centaur helicopters away from friendly fire. Hunched over his maps and PRC-25 radio, he kept track of the azimuths and max ordinates of incoming artillery rounds, which he passed to me whenever there was a brief lull. The helicopter whipped from side to side as we dodged rising tracers uncomfortably close to our rotor. Suddenly I heard crew chief Specialist “Willi” Williams on the intercom: “Sir, high performance at nine o’clock.” We looked left to see an Air Force jet heading straight at us. I remember “an F-4 screaming in so fast and close I could almost read his name tag.” Our co-pilot at the controls plunged the Huey out of harm’s way. Back at our Cu Chi base, “Willi” found a hole in the floor under Bain’s seat in the back of the helicopter where his radio had been, and a smashed bullet. The PRC-25 had served as the artillery observer’s “chicken plate” armor. The radio was dented but intact and still worked. We saw “Willi” three years ago at a Centaurs reunion and thanked him for saving us; sadly, a few months later he died.